In the last chapter, I discussed Japanese language schools. This chapter features the issues of dual citizenship and marriage that the Nisei faced as they came of age.

When the Nisei were born, their Issei parents submitted a birth certificate to the United States. Many registered births at the Japanese Consulate at the same time. Therefore, many Nisei held dual nationality. When the Nisei came of age, however, they had to confront the compelling decisions of which nationality to keep and/or which country’s citizen they should marry.

NISEI BIRTH REGISTRATION

I found an article about birth registration in 1919 when the population of Nisei was increasing.

“About Registration Procedures for Children Born in the United States” (January 16, 1919 issue of The North American Times1)

As for U.S.-born children who did not apply for Japanese citizenship—in other words, whose parents didn’t submit a birth registration to the consulate—following Japanese regulations, if they travel to Japan, they must register in their Japanese family registry (koseki) temporarily, and then renounce their (Japanese) nationality according to the nationality renunciation law. Or, they may keep dual citizenship for a while and renounce one citizenship later by following the necessary procedures. Either way, they are required to register their name in their Japanese family registry (if they visit Japan) so that future births could be registered at the consulate. People who are already in Japan should go through the procedures in their hometowns.

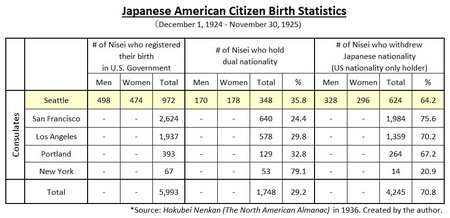

According to some sources, in those days, people born in the United States were required to register their birth in both the United States and Japan and could not renounce their Japanese nationality. As the article above indicated, however, the revised nationality law enacted in 1916 allowed anyone under the age of 17 to renounce their Japanese nationality by following the necessary procedures. From December 1924, everyone, regardless of age, could renounce Japanese nationality at any time. If the birth was not reported to the consulate within 14 days of birth, Japanese nationality could not be automatically granted.

“Nisei Education, Marriage, Employment, and Business Succession” (August 8, 1934 issue)

Consul (Kiyoshi) Uchiyama spoke at today’s special meeting of the Japanese Association about the improvement of Japan–U.S. relations and the transitional state of the current Japanese community as well as its future. Compared to the situation around 1915 when Japanese residents on the U.S. West Coast proposed urgent revision of the nationality law, the change in current society has been absolutely remarkable. He recalled the process leading up to the revision of nationality, citing the petition of the nationality law revision made in the name of the coastal council that year. . . .

In regard to the numbers of birth and nationality retentions, the consulate mentioned that the highest birth rate among Japanese within its jurisdiction was between 1922 and 1924, which recorded 5,000 births nationally, but not even half of those had Japanese nationality. In addition, there are many people who have given up their Japanese nationality. I, in recent years, the number of births [in the Seattle jurisdiction] has declined by 10 percent of those of previous years; only one-third of those hold Japanese nationality. Furthermore, considering those who have renounced their Japanese nationality, the majority of Nisei retain their U.S. nationality only. He expressed his desire for us to conduct sufficient research in terms of Nisei education, marriage, employment, business succession, etc.

According to the Hokubei Nenkan (North American Yearbook) in 1928, 972 Nisei were born in the jurisdiction of the Imperial Consulate in Seattle between December 1924 and November 1925. Among those, 348 Nisei (approximately 36 percent) were dual citizens with both American and Japanese nationalities. The remaining 624 were American citizens who had renounced their Japanese citizenship (Table 1).

DUAL NATIONALITY ISSUE

“Nikkei Citizens Should Renounce Japanese Nationality” (February 18, 1938 issue)

Lieutenant Colonel Jamus Earl Mahahui, deputy commander of the American Legion, argued that the Americanization Committee of the American Legion at Hawaii branch should take the lead in starting a movement for Nikkei citizens to withdraw from Japan.

“In order to make this movement effective, we must first educate Japanese parents. To that end, the United States sincerely welcomes Japanese Americans, but I must preach the necessity to renounce Japanese nationality and show loyalty only to the United States.”

In response to Lieutenant Colonel Mahahui’s proposal, Sumiyoshi Arima (North American Times president & publisher) said the following in his column “Hokubei Shunju” in The North American Times:

“Nikkei Citizens Quit Japanese Citizenship” (March 28 and 29, 1938 issues)

The issue of Nisei dual nationality has been often debated, cautioned, and warned against to this day, and this must be ultimately resolved. This dual nationality arises from an unusual legal status reflecting a fundamental difference between the nationality law of Japan and that of the United States. This is an atypical status from the principle of nationality and the principle of territoriality. The state demands absolute loyalty from its citizens. . . .

We have no objection to Lieutenant Colonel Mahahui’s opinion about renouncing Japanese nationality. I think that it is a natural opinion as an American. This opinion was rather a warning and a caution with good intentions toward the Japanese people. . . .

I think the simplest way to solve this problem is to let the Nisei decide their nationality by their own will as soon as they reach the age of 20. However, theory and practice may not necessarily match and also may readily cause profound issues. Even though their nationality was clearly determined by law, their social treatment and status were relatively unfavorable to them so that they often faced disappointment. Therefore, we would like Americans to see the position of Nikkei citizens with greater sympathy and understanding.

“Dual Citizenship Will Become an Issue in the California Legislature – Anti-Japanese Representatives of the House are Scheming Against It” (June 10, 1939 issue)

The Japanese American Citizens League has made every possible effort to prevent the passage of anti-Japanese bills in the California legislature. Their effort has been successful. Attorney (James) Sakamoto*, president of the JACL, warned that “some of the anti-Japanese state legislators tend to raise the issue of dual citizenship among the Nisei.”

He further added, “I heard that anti-Japanese state legislators are working hard to pass anti-Japanese fishing bills and anti-Japanese land bills, but have failed terribly so now they are trying to question Nisei loyalty to the United States. Therefore, the Japanese American Citizens League in each region needs to bring up these issues with their parents and obtain their understanding. We need to encourage Nisei who are dual nationals to select only one nationality.”

In response to this article, Arima wrote the following in his column “Hokubei Shunju:”

“Nisei Dual Nationality Issue Needs a Solution” (August 2, 1939 issue)

The Nisei dual nationality issue should not be left in this state forever. The dual nationality of minors should not be decided solely by the will and convenience of their parents; therefore, this issue is practically unavoidable. But men and women who have already reached the age of 20 should decide their nationality by their own choice. This is something that must be taken into consideration before America would interfere with this issue, and the time has truly come.

Arima insisted that dual nationals should renounce their Japanese nationality so the Nisei could establish themselves as American citizens and ensure the survival of the Japanese American community on American soil.

Note:

1. All article excerpts are from The North American Times unless noted otherwise.

*Editor’s note: James Sakamoto, national JACL president (1936-1938) was not an attorney.

*The English version of this series is a collaboration between Discover Nikkei and The North American Post, Seattle’s bilingual community newspaper. This part was originally publishd on May 28, 2023 in The North American Post and is modified for Discover Nikkei.

© 2023 Ikuo Shinmasu