Can you take us through your process of writing and collecting information for Sideways?

Most of my memoir is based on stories I recall being told by members of my family. I intended the storytelling aspect of my family’s habits to be represented in my book, Sideways. I relied heavily on my own memories and when I needed more details, I referred to my siblings, most especially Betty and Claude. They were most helpful, often repeating things to me again and again as I wrote and edited my story. This correspondence took place via email, which was very useful, because their responses could be saved on my computer.

Other times, I made things up, when I needed to embellish my story for dramatic purposes or to streamline events in order to keep the events moving forward. This is why I call my memoir creative nonfiction––all the while keeping in mind that if you talk to two people about an event, chances are they will recall that event differently. So a writer must evaluate and fashion the story to satisfy the curiosity of the reader while maintaining the authenticity and truth (if not necessarily each and every fact) of the story.

I also wrote to Roy Miki, again via email, to ask him about his family’s history in Haney, BC and the circumstances of his birth in Winnipeg. He was very helpful and I am indebted to him for his generosity. It helped, I think, that he knew William Hohri, my former Sunday school teacher, through his work in the redress movement. Rose and Richard Murakami of Salt Spring Island fame were also very helpful.

It took me three years to write Sideways: Memoir of a Misfit. I wrote it with the help of the members of the Uphill Writing Group, the group I joined after the immigrant women writers’ group disbanded. Brian Deon, Ross Klatte, and Sandra Hartline offered suggestions that were instrumental in making my story ready for publication.

The first chapter of Sideways was shortlisted in the 2013 The Malahat Review Open Season Competition for Creative Nonfiction and was published in the 2014 spring issue of The New Orphic Review.

Your chapter about your brother Claude sticks out for me. Can you go into the racism, how ‘American’ or ‘Japanese’ were your siblings and were those conflicts ever really settled amicably?

The chapter “Claude and Me” is one of my favorites because the story allowed me to reveal aspects of my neighbourhood in Chicago that I otherwise may not have done. I do believe that racism played a significant role in the lives of my family. How could it not? It also plays a significant role in the lives of all who grow up in an unequitable democracy, whether we are aware of it or not. Racism can give people a sense of false superiority, just as it can give others an equally a false sense of inferiority.

Self-hatred plays an undeniable role in the lives of all minority people who grow up in North America. Even in a country like Jamaica, which is far more homogenous than, say, Canada or the United States, colour still plays a determining factor in how one is perceived, despite all the political rhetoric to the contrary.

When he was a child growing up in Hood River Valley, my brother Claude, unlike Flora and Betty, was never invited into the homes of the whites and when his friends failed to show up at the train depot to say goodbye I think he was permanently scarred by their betrayal. I believe this is why he still lives in Japan today.

I believe envy and competition played a very harmful role in our family dynamic. First, there was the envy my grandmother felt for my mother, and second, the power my grandmother wielded to dispense special privileges to her favorite grandchildren. Her tyranny caused trauma in the children who felt demeaned by her bias and inspired an unhealthy sense of entitlement in those she loved best.

On top of all this cruelty was the poverty and the number of children who were forced to share the affection of their mother and father, who were overwhelmed by racism, the irresponsibility of my father’s parents, and their obligations to relatives in Japan.

You can figure out why it is you feel the way you do through psychotherapy. But that discovery doesn’t alter the past. The hurt remains and plays out in the behaviour of the descendants. Nevertheless, I do think it helps to bring forth out of our subconscious the hurt we feel, so we can affirm those feelings with our own awareness. In this way, we can learn to take responsibility for our future happiness.

Writing my memoir helped me to come to terms with my past. As I wrote Sideways I learned to appreciate in greater depth the strength of conviction and the commitment of intellectuals like William Hohri and Gordon Hirabayashi, who chose to live independently of how they were defined by society.

I think it is particularly tragic that America still promotes the belief that those who are rich are inherently superior to those who are poor. It is this belief that informs the bankruptcy of the American Dream. There’s nothing anyone should feel ashamed of because they have to work for a living. I, for one, have great admiration for people who work with their hands, and that includes musicians, craftsman, repairmen, and carpenters.

I believe my siblings, with the exception of Fumiko who grew up in Japan, identified strongly with America, even though one of them lives in Japan through choice. Claude still refuses to take out Japanese citizenship after living there for over a half a century. None of them, to my recollection, ever cultivated close friends or married outside their ethnicity; so they’ve effectively insulated themselves from rejection in this way.

The four eldest of my siblings are dead. Of those still alive, Flora lives in an assisted living residence in Chicago. My brother, Junior, lives in Chicago as well, in his own home. Betty lives in San Jose, California, where she and her husband moved to begin a business.

Unlike myself and my husband, they have experienced acceptance from their inclusion in an ethnic community. My husband, my son, and I have been forced to fend for ourselves in Canada because we are an interracial family that does not have an extended family here. My husband and I were an interracial couple before it became a trend among the Nikkei to marry outside their race. We do not wish to be identified by any group, social, religious, or political because membership in a group often forces people to make uncomfortable compromises.

However, autonomy makes for a difficult life––but one that is not without its rewards. Oddly, once I publicly declared that I was a misfit, people have taken my story to their bosoms, and I have found an unexpected fulfillment in their appreciation of my story.

What about your siblings?

My siblings worked hard and stayed within their own ethnic groups. Growing up in America was easier than it was for the Japanese Canadians. Japanese Canadians were not allowed to live in ethnic communities even when they were forced to disperse beyond the Rockies. The “one Jap per town” mandate mentioned by Joy Kogawa in the film, Children of Redress, is why there are no historically ethnic Japantowns in Canada as you can find in LA, San Francisco, and San Jose.

This unfair directive encouraged greater interaction between the Nikkei and the white populations––and to everyone’s astonishment, the greater likelihood of interracial marriages, which was not welcomed by either group, I’m told. According to one account, a couple was forced to run away to Coeur d’Alene, Idaho to marry because no official in Canada would accept Japanese Canadian identification cards. The Japanese individual in question was forced to identify as a Hawaiian in order to be married in the United States.

The “one Jap per town” policy forced Nikkei families who were expelled “East of the Rockies” to be deprived of the affirmation of their identity. When I first moved to Toronto in the late Sixties, there were no Japanese restaurants in the city and only one store where I could buy Japanese food items. The policy requiring Japanese Canadians to pay for their own internment defied the Geneva Protocols for the treatment of prisoners. The procedure devised by Ian MacKenzie and G.W. McPherson to confiscate and sell off their properties stand out in the magnitude of its guile and malfeasance.

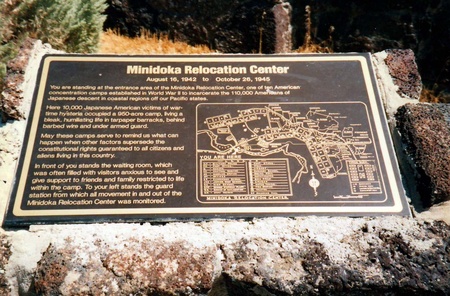

Living in a community is easier than living an isolated existence. That said, I don’t think it was easy to be sent to fight in the worst combat theatres in Europe as a soldier in the American military. Or to endure the simultaneous military enlistment of three sons as Tamaki Onodera experienced while being held captive in Minidoka. Satoru, her eldest son, was killed in combat.

I think the question of whether it was easier for a Nikkei to be imprisoned in the US or Canada can be likened to asking a Jew whether it was easier to be tormented in Dachau, Auschwitz or Buchenwald. It really doesn’t matter where exactly these injustices occur. All we need to know is that all instances of wrongs committed against the Nikkei in North America during World War II were devastating and caused abiding psychological trauma to every person who was victimized. I know of three Issei men who committed suicide after their release from imprisonment: one failed trying to re-establish the life he knew in California before he was imprisoned in Heart Mountain, Wyoming; another killed himself in Alberta; and the third was a Japanese Latin American deportee who committed suicide in Chicago.

I was particularly upset when I heard that the captive Nikkei in the Kootenay were forced to walk several miles from New Denver to the Slocan to buy food from local farmers. Sometimes the internees would return “home” with half a turnip. So desperate was their plight, Japanese nationals sent food shipments to their relatives here in Canada through the Red Cross. It was no wonder that the New Denver internment site was eventually turned into a TB sanitarium due to the number of detainees who developed TB from their inhumane treatment during their captivity. According to one article in The Globe and Mail published on July 21, 2013, hundreds of elderly internees died during their detention in Canada during the war.

We can try to come to conclusions as historians and sociologists, but the truth is, we don’t understand what an individual feels or how an individual will react when he is persecuted. We can use statistics to determine length of imprisonment or the number of people incarcerated, even perhaps the number of internees who were shot and killed, became mentally unstable, or died from illness. But the depth and magnitude of suffering is uniquely individual and memory is crucial in defining the narrative of our country. It is this narrative, not the dry statistics, that provides insights and shows us the way to improve society.

Finally, what are your greatest hopes for the Nikkei community both here and in the US?

My hope for the Nikkei in Canada and the United States — and for everyone — is that we begin to think openly and critically about our countries’ histories and embrace our stories. It is through respect for our failings, as well as our dreams and accomplishments, that we learn to love ourselves.

© 2016 Norm Ibuki