Japanese mixed with English

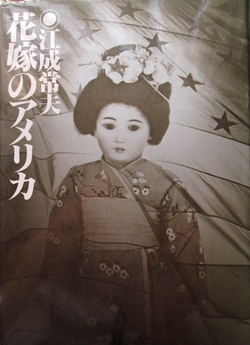

In February 2016, I picked up a book for the first time in 30 years. Last year, my 18-year-old son, born in the United States, graduated from high school in the suburbs of Los Angeles and came to live with my parents in Japan. I stayed there for three weeks to help him set up. While I was going through various procedures, such as obtaining a resident registration card, joining the National Health Insurance, purchasing a mobile phone, and opening a bank account, I diligently sorted out the large number of books and magazines that had been left in my former room and would soon become his. Among them was a book called "The Bride of America."

This book contains interviews and photographs of Japanese women who married American soldiers and crossed the ocean during the period from the end of the war to the Korean War. The author, Enari, moved to Los Angeles in 1978 and continued to interview women through word of mouth.

"Benbridge, Maryland is the last station. How do you spell it? I don't know. Anyway, we're training the Navy..."

(From Marie Hauser's entry)

I was impressed by the amount of English used in the writing. I honestly wondered at the time whether it was possible for someone who had lived in America for so long to use so much English. However, I was drawn into each of the women's monologues, and in the blink of an eye, I had finished reading the interviews with nearly 100 women.

Honesty and toughness

How they met American soldiers, decided to marry them, how their parents accepted their decision, and what life was like after they went to America - their stories are vividly told for each woman. What surprised me 30 years ago was how honest they were. During the war and the postwar period, when there was nothing to eat and they were poor, they could earn much higher wages by working as maids in stores and homes related to the American military, and they could live a rich life that was different from the postwar period. Many of the women looked back and said that it was only natural that they were attracted to cheerful and carefree American men, unlike the tired Japanese men.

Many parents were not happy with their brides choosing Americans, who had been enemies until just a short time ago, and especially soldiers. Some brides were told never to return to their hometowns. Still, they pinned their hopes on a new life and crossed the ocean with the man they loved. Some say they never set foot on Japanese soil, while others confess how happy they were when they returned home with their newborn children and their whole family was there to greet them at the airport.

Her husband's parents' reactions to her in America were also mixed. Some parents made racist remarks when they saw the baby's face, saying things like, "You're whiter than I thought," while her mother-in-law, who couldn't speak English, took her to the library and read the baby picture books to her.

Although each person's circumstances are different, what I felt was common to all the Japanese women was their honesty and strength.

Not many women stayed with their first husbands until the end. One woman lost her husband in the Vietnam War. Another lost her husband suddenly during the hippie era, never to return home. There were also many women who divorced their husbands because of their partners' infidelity. Nevertheless, the women Enari interviewed continued to put down roots in America and live on. "I had to stay and work hard in America for the sake of my children, who I had raised as Americans," they said, reflecting on why they did not return to Japan even after divorcing or losing their husbands.

Their strength is also apparent in the family photos that accompany each interview. Their expressions as they gaze straight into the camera give off a sense of dignity. However, to protect their privacy, several of them are anonymous and appear without photos.

The brides were real

By reading this book, I learned that there were people who crossed the ocean for reasons other than studying abroad or business. Ten years later, I quit my job at a Japanese publishing company and moved to Los Angeles alone. The reason was not to study abroad or to be stationed overseas, and certainly not to get married. It was "a long vacation, a reward for myself."

A person I met the year I went to America took me to a church where Japanese people gather. There, I discovered that the women I had read about in "The American Bride" were real people. They were in their 60s and 70s and called each other by their English surnames, "Ms. Smith" and "Ms. Harper." In the same tone as the monologue in the book, the former brides said, "I came to America when I was 1955." They fried tonkatsu in the church kitchen, showed each other pictures of their grown-up children, and chatted happily in Japanese mixed with English. Everyone looked happy.

No matter how hard they struggled, their determination to "bet on America" as they crossed the ocean must have been much stronger than mine, which I thought lightly, "If there's no job in Los Angeles, I can just go back to Japan." In the end, I got a job and a visa at the only place I interviewed, got married, and had a child. My son, who I was supposed to have raised as an American, became obsessed with Japanese anime and manga, and declared that he would "go to school in Japan after graduating from high school," and he did just that. However, the reality of Japan is probably not the dream country he imagined. When he realizes this, will he be able to stay and say, "It's my decision to go to Japan"? After rereading "The Bride of America," this thought crossed my mind.

© 2016 Keiko Fukuda