Recently, I did a memorial piece for Nichi Bei on my late friend Franklin Odo, a Hawaii-born Sansei. I referred to the piece as a kaddish (mourner’s prayer). I meant it as a tip of the hat to Franklin and his longtime interest in Jewish Studies. Franklin was so absorbed that he even co-taught a course with Professor Wendy Bergoffen at Amherst College on Jews and Asians in America. It occurs to me now that it was one of the rare occasions when I have mentioned Jewishness in my columns, and implicitly addressed my own Jewish identity.

Recently I have been reflecting more seriously on my sense of the connections between Japanese Americans and Jews, and the influence of my own ethnic heritage on my study of Japanese American history. I wanted to share here some stories that illuminate the subject. A warning: my discussion of the subject is nonlinear and punctuated with jokes, in proper Jewish style.

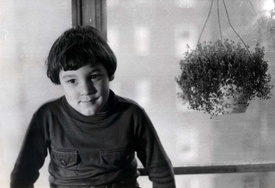

- I am a small boy, 3 or 4 years old. I am riding with my older brother in an elevator at our apartment house in Bronx, NY. An old man, for whom Jewishness is clearly an essential element of his identity, asks my elder brother and me if we are Jewish. My brother answers, “Yes”; I simultaneously respond “No,” as I have no sense of any such thing (looking back at it, 50+ years later, I can only imagine what that old man thought).

Sometime later, my parents try to explain to me that even if we do not follow the Jewish religion, and in fact they are convinced atheists, somehow we are Jewish all the same. In later years, I will make a stock joke of how I disappointed my parents: they raised me to be an atheist, but I have doubts about the nonexistence of God!

- It is 2008. I am going with my friend Paul Okimoto to visit my new friends Yasuo and Lily Sasaki at their home in Berkeley, CA. I am excited to get to interact with these ageless Nisei masters, who have been active in literature throughout their long lives. Yas founded the first Nisei literary journal, Reimei. in Salt Lake City in 1931. He is also a noted doctor and scientist. Lily, a member of the fabled Oyama family, is an artist and journalist.

When I come into the house, they are speaking to their grandson. The first words that they greet me with are, “So, Greg, what is it about Japanese and Jews?”

I am not sure of either the nature of the question or of why they are asking me—Do they know that I am Jewish, and think I will thus have some sort of expertise? Or do they imagine that I have turned up important information in my research? Or was it just the last thing they were talking about before I walked in the door, and they wished to add me to the conversation?

Not sure what to say, I deadpan, “All I know is that Japanese Americans and Jews are different in one important way: Nisei mothers tell their kids, ‘Eat everything on your plate or I’lll kill you,’ whereas Jewish mothers tell their kids, “Eat everything on your plate or I’ll kill myself.’” They laugh, and the conversation soon turns to other things.

- It is 2010 and I am at the Japanese American National Museum with a set of distinguished scholars of Japanese Americans, who have been called on by the writer Patricia Wakida to advise on a new permanent exhibition. I am especially glad to see Brian Niiya among the scholars, as I admire his efforts to preserve Japanese American history.

He tells me that he has been hired to edit a new online Densho Encyclopedia and asks me if I will work with him. Brian is generous in his flattery: he tells me, “I was heading the Japanese Community Center in Honolulu over the past decade, and largely missed the new scholarship in the field during that time. I just started catching up on it, and I find that Greg Robinson alone wrote half of it!”

During a break in the meeting, Brian comments that all scholars include a heavy dose of autobiography in their writings. For instance, Eiichiro Azuma, himself an immigrant from Japan, writes primarily about the Issei generation. Linda Tamura, a native of Hood River, Oregon, published a book on the Japanese community of Hood River.

I ask Brian how my autobiography shapes my writing. He thinks for a moment, and then responds, “You write about connections between members of excluded groups.” I have to smile, as I can see that Brian “has my number”: there is a good deal of truth in his words. While I know that he is not speaking specifically about my Jewish identity, I am conscious that my sense of empathy with others reflects that background. - I am speaking to my friend Arthur Hansen about The Principled Politician, Adam Schrager’s book about wartime Colorado governor Ralph Carr. It was Carr who gained a reputation for integrity (somewhat exaggerated, in my view) after welcoming Japanese Americans to his state. Art recounts that some time previously, he had hosted a discussion with Schrager at the Japanese American National Museum. When Art asked Schrager how much his own experience as a Jew had informed his portrait of Carr, Schrager had been visibly ill at ease with the question. Art tells me that he cannot understand Schrager’s reaction. It is not like Schrager’s Jewishness is a secret—he is active in Jewish community activities in Colorado.

In any case, Art notes, the question is only logical, in that so many of the non-Asians who are specialists in the field of Japanese American history are Jewish, such as Morton Grodzins, Roger Daniels, Stanford Lyman, Eric Muller, and myself. Art says that as a Gentile, he is more the exception among scholars of the Nikkei.

I respond that I cannot speak for Schrager, whom I do not know, but that I surely would be abashed if I were speaking at a public event and someone asked me how my Jewishness influenced by study of Japanese Americans. I tried to explain why: Because I would like to think of myself as universalistic and not as a member of a particular (small) community. Because the influence of my ethnic heritage is diffuse and partly unconscious. And mostly because I have no clear sense of that aspect of my identity.

As the writer Jonathan Miller said, “I’m not really a Jew. Just Jew-ish. Not the whole hog”. I am well aware that, unlike Japanese Americans, my ethnic difference is not apparent, so I have the luxury of being able to get away from it if I wish—especially with a goyish sounding name like Greg Robinson. (And no, in case you are wondering, it is not an Ellis Island name. The family name was Robinson—or Robinsohn—even in Eastern Europe, though the Greg part comes from the name of an Irish-American friend of my father’s who died young). I would never hide being Jewish, but I don’t want to be limited or pigeonholed because of it. - In the archives of Norman Thomas, the Socialist Party leader and wartime defender of Japanese Americans, I find extended correspondence from Kiyoshi Okamoto, mentor and inspiration for the Heart Mountain draft resisters. I am fascinated and horrified to discover that Okamoto’s writings, especially about the government, are laced with anti-Semitic jibes and conspiracy theories.

I mention this to the redress activist William Hohri, and he explains that anti-Semitism was endemic in prewar Japanese communities. I am reminded of the joke attributed to Isaiah Berlin, among others: “An antisemite is someone who hates Jews more than is absolutely necessary.”

I do research on the (often negative) images of Jews in the prewar West Coast press, which I then compile into a chapter of my book After Camp. I name the chapter, “From Kuichi to Comrades.” (For those readers not versed in Issei Japanese, Kuichi is a slang word composed of “9” and “1”—which when added together form “10” [i.e., Jue]). It is more or less the first time that I have ever published anything in American Jewish History. It is only through the lens of Japanese Americans that I find a way to write something on the history of my own group. - I am invited by a friend to consult with him over his manuscript, which has a section on prewar Nisei. I mention that many Nisei who grew up attending Buddhist churches lacked any special knowledge of or devotion to the faith of their fathers, but maintained their attachment to Buddhism out of ethnic identity. As things Japanese became increasingly stigmatized in Christian America, the attachment of Nisei to Buddhist practice and identity apparently increased. Affirming their religious identity was a way for them to show solidarity with their embattled community.

I point to the parallel example of second-generation Jewish Americans, many of whom ceased keeping Kosher or even believing in (the Jewish) God, but who continued to attend their local synagogue, or at least to celebrate Passover and Hanukah as family holidays. In the wake both of the Holocaust and of the entry of Jews into mainstream American society, their synagogue attendance actually increased.

I tell a joke about a Jewish Robinson Crusoe who lives alone on a desert island, where he builds two synagogues: “One is the synagogue I pray in, and the other is the one I wouldn’t set foot in if you paid me!” My friend asks how I have such insight into Jewish life when I never belonged to any temple or religious community. I tell him “From my mishpocheh” (extended family). But that is only partly true, since mine is not a big family, and most of my family members have married non-Jews. In actual fact, my knowledge of Jewish communities comes from reading and speaking to my elders.

After all this, I still am really not sure precisely what being Jewish means to me, still less how it flavors my view of Japanese American history, though I am aware that it must. Ironically, the most direct influence of my ethnic heritage may be in my interest in studying the history of Japanese North Americans and the Catholic Church—precisely because I want to learn how Catholics, themselves a minority in Anglo-Protestant America, related to Asian Americans.

When I first come to my friends, the historians Matthieu Langlois and Jonathan van Harmelen, to propose that we all write a book together on the subject, Matthieu assumes (incorrectly) that Jonathan, because of his Dutch name, is from a Protestant family. I tease Matthieu, “You just wanted to start our project with the line, ‘A Jew, a Catholic, and a Protestant walk into a book together!’”

Perhaps working on the Catholic project may ultimately help me better understand how Jewish I am, and also how I am Jewish.

© 2024 Greg Robinson