TN: Do you think you make art as a way to fill in those gaps or to speak to these silences that are created by the lack of having these these artifacts or heirlooms?

RT: Yeah, probably that, and certainly my father had a lot of stories that he would share. And honestly some of them were really like “what?” I was probably too young to handle some of these but they left a very intense mark on me.

So I think part of it is just trying to recover what the hell…it was his sense of heaviness and why the hell was he telling me this story, like “I didn’t have anywhere to go, and my car died and we couldn’t fix it so we had to push it over a bridge into the river and I had to hitchhike into the next town.” And I was like five or six, and [I would think] “that was scary, what happened?”

Just trying to recover what happened to them and he also would talk about things like, “Oh I had this thing, what did you do with it?” They would fight, my parents would fight, and my mother was saying, “I had to give that away,” and he would say, “Oh man, I wanted that thing, I wanted that suit.” So I would always go, “where is that suit?” Trying to reclaim and understand these pieces that are lost and also, where are these photos, what are these images connected to? Who are these people?

TN: Well, I get that. I know that asking artists is a tricky thing with these kinds of questions, but I’m just curious if you have an answer—one of the things that I love about your work is that there’s this urge to create visual art out of documentation and not just document.

And so I’m wondering if the creative impulse for you always begins with the urge to document and then you create, or is it always you’re always just working in this space of documenting and art making. Does that make sense?

RT: Hmmm. I think it’s because I watched my father do this so much. He was always was taking photos of things and then we had, sadly, a lot of images that were lost. So that’s probably also me trying to create more, reclaim this.

But you know there were tons of things that he was always shooting, so I and then sometimes I would see those things as slides or whatever and I just felt this sense that materially we had to kind of constantly keep producing these things, these documents, or these images.

Actually he gave me a camera, and then he was very terrible about showing us how to use [the camera]. You know, “read this book,” and “you just go read that.” And I would ask him a question, and he would just like, [growl], and he would just be really cranky.

And I tried to take photography classes at Cal Arts, and I did do some photography. Somehow it didn’t take, and also I can remember trying to learn all these technical things, like learning 16 millimeter, or in video, and somehow my brain could not could not grasp it.

Then suddenly I had something turn, and it finally just started to make sense. It was really a lot of working through a lot of weird stuff and then finally in my 30s I finally kind of got it: how to edit, how to do these things.

And then I think, interestingly after he died and then I was taking care of my mom, starting to hear my mom, and then…well, the technology change of digital cameras became available, and I had to document a lot of things in her house. And then pretty soon I was taking photos of these things in her house. Because it was really interesting, the feedback that I got was pretty immediate, so I could really correct and learn from what I was doing. And then I really got into photography from that.

Obviously I was filmmaking before that. But somehow the actual still images just became very important in the way that still images became important for my father. Photography is really a big interest...in terms of the art form and the sort of visual culture and both historic and otherwise aesthetic, it is really interesting to me. How to unpack an image and the meaning of an image really figures into my work a lot.

TN: How —this is probably not the right word—but how to animate an image, how to enliven an image seems to be something [you work with]. Because when I think of your work I do think of these still images and this sense of movement that, not “make it a cartoon” but that it moves, somehow, in more ways than one.

The last question I have for you is about these retrospectives [of your work] that are happening. How does it feel as an artist to be having retrospectives now at this point?

RT: It’s exciting, it’s really exciting. I think it’s a little bit overwhelming, too. I haven’t been able to take it in but...It’s interesting too because I feel that also I am moving, I am shifting the way that I work. And so it does seem like you have this one sort of body of work, and I feel sometimes a little bit too like. I really wasn’t going to make a lot of work during that time I was taking care of my mom, about ten years. [I was feeling] very stuck and very overwhelmed and very sad, so I wasn’t feeling very productive, and I almost left filmmaking. I thought, I don’t know…

And then I came back to it and started teaching and a lot of things were happening, and…I don’t know, I feel like I don’t have a lot of work to show, but…I do feel like I’m in this different phase now, and thinking about the work differently, and how I want to produce things, how I want to make things, in this certain way towards, I don’t know, how to tap different audiences, maybe different ways of framing the work too.

TN: When you say “shifting the way you work,” what kinds of things emerge when you talk about that?

RT: I think one of the things that happened is that I have a lot of questions about documentary, right?

TN: That’s clear in your documentaries, which I love.

RT: Yeah, so we created that [beauty shop] set [in Wisdom Gone Wild], I wanted to do more set pieces, when I was making this film. We couldn’t do it because we didn’t have the money and my mom was really fading so there wasn’t a lot of time to put resources. But we got the beauty shop, and we had the streamers [at the museum], I wanted to do one more but we couldn’t get that together before she passed away.

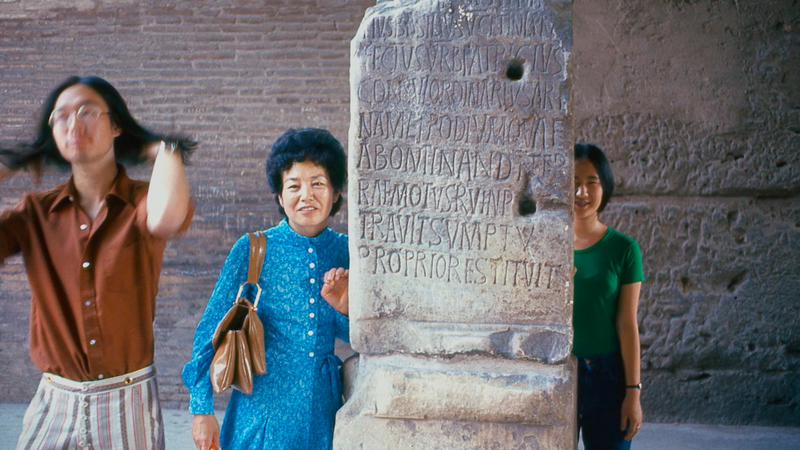

But I’ve been thinking about, with the photographs of my father, that I really am interested in sort of unpacking these and creating set pieces around or both… Kind of looking at these locations as they might be today and if we can trace them back but also working with actors. We found a lot of the newspaper articles that he wrote.

So finding ways to voice those, the writing, and so I have a lot of different ideas about that. Creating set pieces and having different actors play my father across different time periods.

TN: I know this [film] took a long time and it’s so clear that it took so long because there’s so much care in all of it. But I think it was worthwhile. I hope you feel that way, that it was worthwhile, because the result is so beautiful.

RT: It was so hard. I kind of felt like I didn’t know what I was doing, but I also had the faith that there was something that I was trying to figure out.

At that point I kept going but there were times when I was just like, “what do I do now?, maybe this footage is just really not worth it.” But it’s just a question of making a commitment and then bringing on the editor, the last editor, Catherine Hollander, we just figured out our way.” I said, “I have to find the language of the film, before bringing anyone in, because if I find that language, then I can sort of teach it to you.”

So that’s what it took. I think I was leaning into my editors, like “oh, this is so heavy.” I was leaning into them, and they were trying to do what they knew how to do, but then I would look at it and go, “This isn’t what I wanted. I have to take it on, I have to create that language.” No one else can do that.

© 2023 Tamiko Nimura