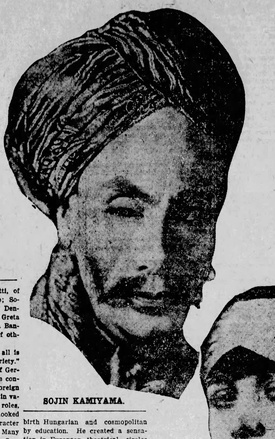

Among all the Japanese actors who graced Hollywood screens in the silent and early sound eras, perhaps none had such a charismatic and powerful presence as Sojin (Kamiyama). Though he spent only a relatively short time in the United States, and never attained the level of stardom of his contemporary Sessue Hayakawa, his work attracted attention and won him fans on both sides of the Pacific.

Sojin Kamiyama was born Tadashi (AKA Tei) Mita in Sendai, Japan, on January 30, 1884. He grew up in Japan and attended Waseda University. As a young man he married Chie Mita, who used the stage name Uraji Yamakawa (Chie will be the subject of part II of this article).

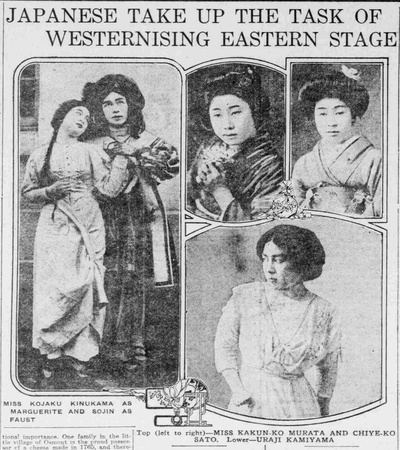

In the 1910s, the Kamiyamas joined with Takashi Iba, Taro Akiba, and Toshio Sugimura in establishing the Kindai-Geki Kyokai (Modern Drama Society or Modern Players Society), a theater group for producing contemporary drama. Its opening production was Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler at the Yurakuza Theatre in Tokyo.

In the next years, the couple achieved renown as leaders of Japan’s new theater movement, producing and starring in plays by Shakespeare (Sojin was acclaimed for his performance in King Lear), Chekhov, Ibsen, and Tolstoy. In 1913 the Association performed Shakespeare’s Macbeth under the guidance of an English director. They put on further productions at Tokyo’s Imperial Theatre.

In 1918, Sojin appeared in a production of Oscar Wilde’s biblical drama Salome, translated by his friend, the eminent novelist Junichiro Tanizaki. The same year, he published a novel, Rengoku (Purgatory).

In winter 1919, Sojin and Uraji left Japan on a tour of the West. During a stop in Hawaii, they starred together in a notable production of Shakespeare’s Merchant of Venice at the Asahi theater. After their stay in Hawaii, they sailed for the mainland on the Shinyo Maru. Upon arrival, they expressed their intention to study Occidental drama in the United States and in Europe. Sojin stated, “The Japanese take a great interest in romance. They want a real story and they want it well presented. But lately they seem to have fallen back on their first love, the kabuki, the old classic Japanese play.”

They traveled to Los Angeles, where they were hosted by film star Sessue Hayakawa. There, they investigated motion picture production. During their time, they signed a long-term contract with producer Lorimer Johnston to produce films in Japan, where they intended to return. According to one source, they started a film company in California. In either case, the film production business did not prosper. They soon abandoned it, and moved to Seattle.

Once in Seattle, the couple took up journalism. At first, they worked for the Tacoma Jiho, a Japanese newspaper in Tacoma, Washington. By 1922, Sojin had founded his own newspaper, the Tozai Jiho, and also produced a journal, the Katei, for which Uraji did most of the writing. According to Billboard magazine, they enrolled at University of Washington during this period to improve their English.

Ultimately, Sojin was attracted back to Hollywood to take part in silent motion pictures. His first real role was in Douglas Fairbanks’s 1924 Arabian Nights swashbuckler The Thief of Bagdad. Sojin took the part of The Mongol Prince, a Chinese royal who wooed the princess of Bagdad. The film costarred the rising actress Anna May Wong as the Prince’s sister—one of eight silent films in which she and Sojin would work together (the cast list featured as well the legendary playwright/critic Sadakichi Hartmann as a magician).

According to one account, Sojin proceeded with filming, though he was deeply distressed by news of the Kanto Earthquake. The report stated that he had spent days anxious for news of a son, back in Japan.

The Thief of Bagdad was a success at the box office, and Sojin’s supporting performance was heavily praised. Its success led Sojin to be cast in some 50 Hollywood films over the next five years. Sometimes he was billed as Sojin Kamiyama or K. Sojin, sometimes under the single name Sôjin.

In the largest number of these, including Soft Shoes (1925), Proud Flesh (1925), The White Desert (1925), The Bat (1926), and The Crimson City (1928), Sojin played villains. While he most often was cast as Chinese, at times he had the chance to play roles as other ethnicities (though only once or twice Japanese!). For example, in The Sea Beast (1926), an early screen adaptation of the Herman Melville classic Moby Dick, he portrayed Fedallah, an Indian Parsee.

When he appeared as an ancient Hebrew jeweler in The Wanderer (1926), the Nippu Jiji commented, “Kamiyama is one of the few able actors of Japan and is staying in Los Angeles to study the subtle ways of cinema acting.” He appeared as a Sultan in The Lady of the Harem, a performance which prompted the San Francisco Examiner to refer to him as a “Japanese pantomimist of great subtlety and power.”

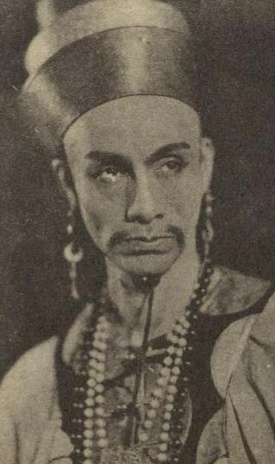

One of Sojin’s most showy roles was in Raoul Walsh’s 1925 film East of Suez, a film set in China and based on a Somerset Maugham story. In it, he portrays Lee Tai, a wicked Mandarin who uses hypnotism and drugs to abduct and enslave Daisy, a mixed-race maiden (portrayed by silent screen siren Pola Negri). Variety enthused, “[T]here is nothing that can beat the characterization that is the work of Sojin. It is perfect. Here’s an artist to the tip of the long nails that he affects for the picture.”

The following year, Sojin was featured in another meaty role, in the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer drama Road to Mandalay, directed by Tod Browning. The film was a Far Eastern melodrama that starred Lon Chaney, the legendary “man of a thousand faces,” as “Singapore Joe.” Sôjin played the part of his sidekick “English Charlie” Wing, a Chinese gangster. Several critics noted the uniqueness of the role, as developed by Kamiyama and Browning.

Instead of playing a stereotyped “inscrutable oriental” in Chinese garb, Sojin was cast as a modern “westernized” man—one of the earliest visibly Asian American characters. He sports “sheik” clothes (including pads with daggers concealed underneath) and cigarette cases. As the Evening Vanguard’s reviewer put it, “Kamiyama Sojin, famous delineator of mysterious orientals, sounds a new note as an oriental educated in San Francisco’s Chinatown, and returning to the Orient with all the American tricks of a big city added to his native sinister traits.”

After his turn as an Asian American villain, Sojin was finally cast in a heroic Asian American role in The Chinese Parrot (1927), as detective Charlie Chan. Although George Kuwa had originated screen portrayals of Earl Derr Biggers’s hero in a 10-part serial in 1926, Sojin was the first actor to take on the role in a full-length feature. Curiously, while the film itself is apparently lost, Sojin’s groundbreaking performance of the iconic Asian American character has inspired the lion’s share of current-day critical attention to his film career.

Although Sojin spoke several times of his wish to return to the stage during the 1920s, his motion picture career kept him busy. In addition, he was a favorite of Japanese American audiences. In July 1926, Sojin visited San Francisco and made a personal appearance before a crowd of some 1,000 people at the Kinmon Gakuen Auditorium, introducing an educational film about Japan’s Davis Cup tennis matches.

Three years later, he made another well-received appearance at a film screening in the New York area. He was the subject of a laudatory profile by Onato Watanna, the faux-Japanese pen name of Chinese Canadian writer Winnifred Eaton, in the magazine Motion Picture Classics in 1928. Watanna stated that Sojin was so versatile that until meeting him, she had never been sure of his nationality.

During 1929, following the advent of the “talkies,” Sojin made his first sound films. He was featured in Herbert Brenon’s The Rescue, adapted from a novel by Joseph Conrad, playing opposite star Ronald Colman. He also appeared in Seven Footprints to Satan, in which he played an evil swami, a member of a cult of devil worshippers living in a haunted mansion.

The coming of sound pictures fundamentally altered Sojin’s career. He struggled to improve his English, but retained a heavy accent. Ironically, because of his established screen persona as a villainous Oriental, his broken English was less of a career-ender at the outset than it was for European actors. Still, it reduced his audibility and restricted the kind of parts he could play.

Furthermore, despite his background in the theater in Japan, the acting style he had developed for Hollywood silents did not transfer well to sound films. In any case, the number of roles available to Asian actors was declining. Already, during the silent era, Sojin had commented publicly that he would likely be the last Japanese actor to play roles in Hollywood, as the future in films belonged to the new generation of American-born Asian actors. He may have seen the handwriting on the wall in terms of his own fate in talking pictures.

In December 1929 Sojin left the United States and returned to Japan. His arrival in Tokyo, after a 10-year absence, was greeted by a frenzied mob of Japanese fans (film scholar Michael Baskett has argued that Japanese fan magazines of the period often misread Sôjin’s Hollywood film roles, overplaying his stardom and influence to boost Japanese racial pride). He took up a vaudeville tour of five Japanese cities, during which he was accompanied by a company of 100 women.

Meanwhile, he was engaged to work in the Japanese film industry. He signed a contract with the Shochiku Film company. and was touted to star in the first Japanese talking picture (the honor ultimately went to opera star Yoshie Fujiwara). He published a gossipy study of the film industry, Sugao no Hollywood [Hollywood without makup].

In mid-1930, Sojin was called back to Hollywood. There he filmed a few low-budget features, most notably the musical Golden Dawn, based on the musical play by Otto Harbach and Oscar Hammerstein II. He also appeared in his last credited American role, The Dude Wrangler, a poorly-received comedy about a dandified urban “pansy” who takes a job at a dude ranch out West in order to impress a girl he loves. During his stay in Los Angeles, he filmed some location scenes for his first Japanese film, the 1931 feature, “Ai-yo Jinrui-to Tomo-ni-Are” (Love, be Forever with Mankind!).

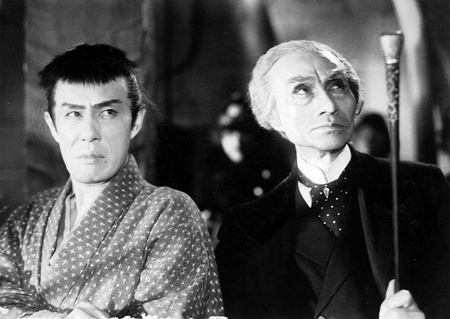

In late 1930, Sojin Kamiyama left Hollywood and returned to Japan, where he settled to work in the Japanese film industry. He returned to California only once thereafter, circa 1935, during which time he again filmed location shots for a Japanese film. Sojin acted in some 30 Japanese films over the next generation, though his days of international stardom were long over and he played mostly supporting parts. His final role was a blind minstrel in Akira Kurosawa’s legendary 1954 film The Seven Samurai. Sojin Kamiyama died in Tokyo on July 28, 1954.

While Sojin’s early Hollywood career has been largely erased from popular memory in the United States, he was memorialized in Japanese filmmaker Nobuhiro Suwa’s 1990 work Actor Sojin Kamiyama, a TV docudrama on Sojin’s life in the U.S. that mixes re-created/reimagined scenes from the actor’s life with documentary material and excerpts from Kamiyama's films. In the process, Suwa’s work explores the relationship between documentary and fiction.

Sojin Kamiyama, like Sessue Hayakawa before him, were among the first actors to face typecasting in Hollywood in “heavy” roles as wily oriental villains. While Sojin achieved critical acclaim and international renown for his performances, the clichéd and painful nature of most of his performances make his surviving films sometimes difficult to watch in today’s climate. Nonetheless, he set a standard of excellence which later Nikkei performers admired and tried to carry on.

Read “Madame Sojin and Eddie Sojin” >>

© 2023 Greg Robinson