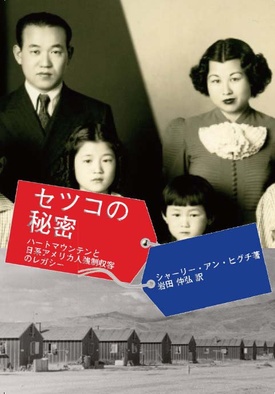

Another book has been published in Japan that conveys the gravity of the fact that Japanese Americans were segregated for national security reasons during the US-Japan war. Many books about the forced internment, or segregation, have been published in both Japan and the US, but the recently published Japanese translation, "Setsuko's Secret: Heart Mountain and the Legacy of Japanese American Internment" (Shirley Ann Higuchi, translated by Iwata Nakahiro, Ecompress), is a well-written book that tells the history and feelings of Japanese Americans through the facts of the internment.

The original "Setsuko's Secret: Heart Mountain and the Legacy of the Japanese American Incarceration" was published by University of Wisconsin Press in 2020.

Author Shirley Ann Higuchi is a third-generation Japanese-American born in the United States in 1959. She holds a J.D. from Georgetown University School of Law, and after serving as president of the Washington DC Bar, she became president of the Heart Mountain Wyoming Foundation, which preserves the site of the Heart Mountain internment camp in Wyoming, one of the places where Japanese-Americans were incarcerated. In 2011, she opened a museum (interpretation center) at the site of the camp to preserve, record, and widely disseminate the facts of the time.

A side of my mother I didn't know

The book is in A5 format, slightly larger than a regular book, and the main text alone is 359 pages. The "Setsuko" in the title refers to the author's mother, a second-generation Japanese American who was interned at Heart Mountain during the war. The author, who is third-generation Japanese, knew the facts, but knew very little about the details and what those experiences meant to her mother and the lives of other Japanese Americans, and for a long time she was not particularly interested in them.

This may be similar to how Japanese people of the author's generation respond to questions about their parents' involvement in the war. However, the difference is not simply a generational gap, but also, as the author says, that Japanese Americans were "model minorities" in American society, and third-generation Japanese Americans had to assimilate into society and excel more than other "normal" Americans.

From this perspective, it could be said that preoccupation with the history of Japanese people with roots in a Japan that fought against the United States was not goody-two-shoes, and therefore they avoided getting too deeply involved in their roots.

However, the author, who had a high social status and was an "honor student" in American society, began to change his perception of Japanese Americans when his mother, Setsuko, was diagnosed with an incurable disease and her remaining days were numbered. This was when he first learned that his mother wanted to leave something behind at Heart Mountain (Setsuko's secret), and after her death, he learned about the experiences his mother had at Heart Mountain.

Confronting Japanese history

In the eyes of her children, their mother, a second-generation American, had striven to live an ideal life in America after the war and put it into practice. However, unknown to her children, she had a special attachment to her experience in the internment camps.

After her mother's death, when she visited Heart Mountain as her daughter, she came to understand her mother's true intentions even more. At the same time, she became aware of her own identity as a Japanese person, and was led to a journey to trace that history. From then on, she worked to carry out her mother's wishes and create a museum on the site to teach people about the internment.

He delves into events related to his roots that he had never looked back on before, and eventually opens a museum with other Japanese Americans who share the same goal. This book can be seen as a record of the author's thoughts and activities leading up to that point, but its core is that it captures the history of Japanese Americans including the war (internment period) through the histories of his own family and the families of prominent Japanese Americans with whom the author was deeply involved in the course of his activities.

The five people who appear are: Daniel Inouye, who was born in Hawaii and served in the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, a Japanese-American unit during the war, where he lost an arm in battle and later served as a member of Congress for many years; Norman Mineta, who left Heart Mountain and served as a member of Congress before serving as a cabinet member under both the Clinton and George Bush administrations; Takashi Hoshizaki, who refused the draft while held at Heart Mountain and was sent to prison, but was drafted and served in the Korean War; Clarence Matsumura, who left Heart Mountain to join the army and helped rescue Jews from Nazi concentration camps; and Raymond Uno, who was held at Heart Mountain and later became the first non-white judge in Utah.

Clarifying the complexities

After the outbreak of war between Japan and the United States, Japanese Americans were forcibly removed from military-designated areas such as California under Presidential Executive Order 9066. They were forced to give up or lose their homes and businesses, and were sent to internment camps set up in 10 locations across the United States.

Like the second generation, they were deprived of their freedom despite being American citizens. They were treated unfairly, but they were questioned about their loyalty to America and were drafted. How should we interpret this? People responded in various ways, depending on their circumstances and beliefs.

While many people left the internment camps to go to the battlefield, some Japanese Americans did not deny the right to pledge loyalty to their country, but felt it was contradictory to have their rights as citizens taken away through internment and then to be told to pledge loyalty to their country and fight. In Heart Mountain, a group refusing conscription, the Fair Play Committee, showed resistance.

The author, who is also involved in the movement to open a museum, considers how to evaluate refusal to conscription. This book brings to light the complex conditions in the camps by accumulating specific examples.

Feeling connected to Japan

The author, who learned of his mother's last wishes and went on to open the museum, was able to get closer to his own roots as a by-product. Until then, he felt like he was in a different world from his Japanese relatives. Also, because he understood that his parents and grandparents were interned because they had roots in Japan, he did not have any deep ties to Japan.

However, in 2019, after being invited to Japan by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, he visited Saga Prefecture, his paternal roots, and while meeting his grandmother's niece and talking about his grandmother, with whom he is both fond, he felt a strong connection to Japan for the first time.

For the author, this was likely a fresh event connected to Japan, but Japanese readers will also be moved by the fact that the interest of Japanese Americans, which had previously remained limited to America, has now traveled back in time and crossed the ocean to Japan.

(Titles omitted)

(cc) DN site-wide licensing statement