Some years ago I wrote a column, “Nunc Pro Tunc,” which recounted my development as a historian and the central influence on it of my late mother Toni Robinson. Today I want to pay tribute to my father, Ed Robinson, and how he has shaped my life and work as a historian of Japanese Americans.

It is a little curious to be doing so around Father’s Day, as it is a day whose existence he refuses to recognize: “I don’t need a special holiday to know that my sons love me,” he has always said. (Actually, his birthday falls during the same period, so I don’t worry about marking Father’s Day, and just double up on the birthday celebration instead!)

I should mention at the beginning that my father has always encouraged my interests and ambitions. He and my mother never missed my band concerts or school plays when I was young, and they sent me off for summer camp and language lessons.

On three occasions when I was a young man, my father took me with him on multiweek trips to Europe to help expose me to foreign languages and cultures. I went around by myself during the day while he worked, and then we spent our evenings and weekends sightseeing together. It was the only extended alone time that I had with him, and I treasured it.

Perhaps most precious to me now is to recall the support that he and my mother gave me in my coming out as a gay man. This was in the 1980s when homophobia was rampant in the United States, and acceptance by families still far from common. I am sure that it was a difficult transition for him. Both my parents took an interest in my new life and interacted with my friends, who adored them and envied me for having them.

In the early 1990s, I met and moved in with my first partner, an undocumented immigrant from Malaysia. There was no same-sex marriage or civil unions in those days, and we faced the problem of keeping him in the country and getting him legal residence. It was my parents who stepped in to sponsor my partner for a Green Card (and eventually citizenship) so that he could stay with me. Even though in the end my relationship with this partner did not last, he continued for many years to visit my father, and always called him “Dad.”

I began studying Japanese Americans in the late 1990s. As I have previously related, I found evidence of Franklin Roosevelt’s prewar race-based attitudes towards Japanese Americans, and that led me to uncover his unexamined role in their wartime confinement. When I embarked on a PhD dissertation on the subject at New York University, my mother threw herself into editing my drafts and studying documents. My father soon also began looking though my sources, reading drafts, and giving me his thoughts. I do not now recall anything specific that he added, but I was greatly touched that he took such an interest.

Meanwhile, my mother and I were invited to present at a conference on Japanese Americans held in Oregon in September 1998. My father flew out with us and drove us around the Columbia River Gorge (our path took us through the town of Hood River, which we found a pleasant and sleepy little place, not realizing its rich and tragic Nikkei history). He attended the conference with us, and impressed the conference-goers he spoke to with his engagement and knowledge. (The historian Linda Tamura, author of The Hood River Issei, brought her own mother and father to the conference, and we bonded over the joy of having caring and supportive families).

When my dissertation was completed, I dedicated it my two parents. While my primary gratitude to them was for producing me, I explained, its contents were also shaped by their interventions. Indeed, although dissertation defenses at NYU were generally closed, my folks were both so deeply involved in my project that they requested and received permission to attend (since my mother was a lawyer, I joked, “Attorney Robinson here is appearing for the defense!”).

Two years later, my first book By Order of the President, drawn from the thesis, was published. My mother and father together paid for a giant book party at NYU, with waiters offering catered food. They invited their friends and relatives, as well as my advisors and other scholars. The pride in their faces at the event reflected their own achievement, as well as my own.

In September 2002, less than a year after the party, my beloved mother died. My father was devastated. The two had been married 43 years and remained at the center of each other’s lives.

Within a short time, my father asked my older brother and me how we would feel about him dating again. My father had been a model, caring spouse all through my mother’s long years of illness, I knew, while my mother had made clear to me during her lifetime that it was my duty to support my father after her passing—including if he wanted to find a new partner. Thus I willingly gave my consent (as did my brother—he even helped my father put together an online dating profile).

It was then, at the darkest moment of our lives, that my father made a most extraordinary request: he asked me to send him a dozen signed copies of By Order of the President, for which he would pay me back. He explained that he wished to have them for dates—he would tell the woman he arranged to date to look out for “the man holding the green book,” then present it to her once they met.

I thought that a work on the “tragedy of democracy” of wartime incarceration might not make a great date gift, and was frankly a bit uneasy at the thought of my book being used as a lure. All the same, I was touched by my father’s evident pride in my writing. Even more, I was impressed by the importance he attached to the wartime history of Japanese Americans, such that his first thought was to enlighten the women he met about the subject.

Within a few weeks, my father met Ellen Fine, an attractive and accomplished woman. They began seeing each other, and have now been living together for some 20 years. I have always wondered if my father had unused copies of my book left over once he met Ellen and went off the dating market, but never felt right asking him!

In later years, my father continued to find ways to show support for my professional work. He read the books and articles that I wrote. He attended multiple historical lectures that I gave, both in English and in French, and went to the book party I held in New York for my second book, A Tragedy of Democracy. (I offered to give him the manuscript to read, but he said that I was now the master, and he could wait to read the book in print).

After my father was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease, he slowly withdrew from public activities. During the pandemic, he remained largely isolated at home. I was stuck across the Canadian border, and could not see him for a period of 18 months. During the first of those months, we had no direct contact. I tried calling and using video, but found that he was unable to maintain a conversation.

Finally, at the wise suggestion of my cousin Sydelle, I wrote him a letter, which his aide then printed out and gave to him. Ellen reported that my father spent the entire afternoon reading, rereading and touching my letter. After that, I wrote him faithfully every week, and made videos to send him.

When I finally saw my father again, in September 2021, it was at a moment of crisis. My father was taken to the hospital (not with COVID) and was not expected to survive. I rushed down to see him and say goodbye. Miraculously, the treatment he received worked, and after two perilous weeks he was able to go back home.

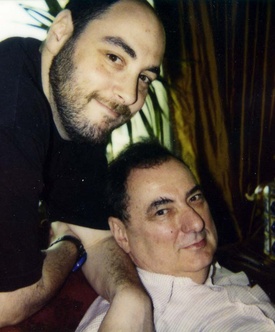

The day he returned was Ellen’s birthday. We had a small family dinner party for her at their apartment. My father was too ill to be present at the dinner table, but afterwards we gathered around his bedside for a bite of dessert. Ellen showed my father the copy of The Unsung Great, my new book on Japanese Americans, that I had given her as a birthday present.

Unexpectedly, my father snatched the copy from her. Despite his condition, he immediately opened the book up and asked for his reading glasses so that he could look through it. To witness my dear father, who had been reduced by his condition to his most elemental self, able to express such pride in me and eager interest in my work was thrilling—it gave me goose bumps. Even now, it is one of my proudest moments.

I have made an exception here to my usual rule about not writing about living people, because I want to record my gratitude and good fortune for having such a wonderful father. His caring for my brother and me was all the more remarkable in view of the fact that he did not have a role model—his own father died when he was just 9 years old. I have always let my father know that I love him, but in my youth I may have taken his unfailing support too much for granted. Not anymore: he is my hero, and I will miss him greatly when he passes.

© 2023 Greg Robinson