Saying 17 out of 30,000 may be an insignificant number. But it is not if what we are talking about are missing people, in a political context like that of the 70s in Argentina when first the actions of parapolice groups in democratic times and then the military dictatorship carried out an extermination plan that had its most violent form of institutionalized repression in the forced disappearance of people. What were they looking for? People who thought differently and this situation, which seems implausible in current times, must be located in a time after the Cold War, in a world divided between capitalists and communists.

“Only those who know the tragedy will understand that the term missing is the worst nightmare for a family… Will he be alive, alive? Is he already dead?... And if he is, where is he? And thousands of more questions.” These questions were asked by the professor at the Ibero-American University of Mexico and the UNAM, Martín Iñiguez Ramos - also a specialist in migration issues -, in one of the prologues of the book “ They didn't know that we are seeds ”, which tells the stories of the 17 disappeared from the Japanese community in Argentina -where only one of them has Japanese nationality-.

The topic is one more link in the many stories collected in all these years - that of the students who fought for the student ticket in the city of La Plata; also that of those young people who attended the National School of Buenos Aires, one of the most emblematic in the country; or the most recent stories of the disappearance of the members of a rugby team, the La Plata Rugby Club. But that of the 17 Nikkei gains its importance because it is a silent community (a documentary on the subject is precisely titled “Broken Silence”), little related to events of political significance, and that in its beginnings as a community was established in the around the Big City, in less populated areas then to dedicate themselves to the cultivation of vegetables and flowers. While a handful of those first immigrants began to install the first dry cleaners.

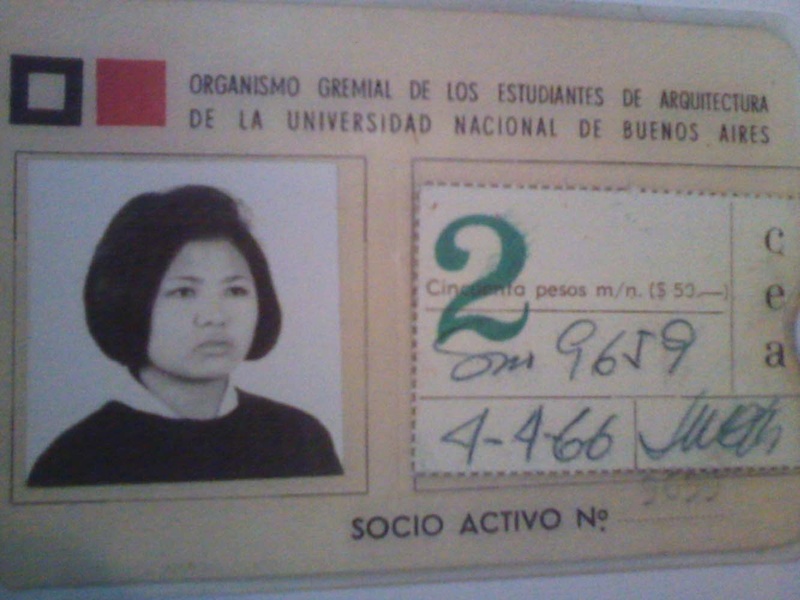

Among the 17 missing members of the Japanese community there were high school students, university students, workers, and political activists. Their stories remained hidden, even with the return of democracy and when the then president of Argentina, Raúl Alfonsín, made an unprecedented and historic decision: to bring to trial those responsible for the covert plan under the so-called National Security Doctrine (objective which legitimized the seizure of power by the Armed Forces and allowed the violation of human rights). However, two women, María Antonia Higa, sister of the Nikkei journalist who disappeared on May 17, 1977, Juan Carlos Higa, and Eduviges Beba Bresolín, wife of Oscar Takashi Oshiro, a labor lawyer who disappeared on April 21, 1977, were the first to get together and initiate a series of claims before the courts, human rights organizations, official agencies and embassies, with little luck.

However, in this almost solitary search at first, Mary and Beba met more members of Japanese families along the way who were looking for their missing children and brothers. Thus, more names were added to the list: Juan Alberto Asato (worker), Katsuya Higa (university teacher and political activist), Juan Takara (accountant), Jorge Oshiro (student and social activist), Juan Alberto Cardozo Higa, Carlos Nakandakare (student), Amelia Ana Higa (university student and political activist), Carlos Ishikawa (political activist), Emilio Yoshimiya, siblings Norma Inés (high school student) and Esteban Matsuyama (university student), Julio Gushiken (worker and political activist) , Carlos Horacio Gushiken (political activist), Ricardo Dakuyaku (university student) and Jorge Nakamura (social activist).

“The destiny of any port is better than one's own, any countryside is better than one's own, any city is better than one's own. Those were hard times when only the dignity of a suit and a dress remained that deteriorated for months in the hold of a steamship," wrote the journalist Ali Mustafa, son of Arab immigrants who, like the Japanese, the Italian and the Spanish ended up forming Argentine society, which someone described as: “ daughter of ships .” The comment is not whimsical and helps to understand why for the children of those immigrants - Japanese included - who had emigrated from countries at war, integration into the larger society constituted a challenge, and for some also, a social and political commitment. .

Jose Chelque, Jorge Nakamura's partner, who disappeared on May 6, 1978, thus remembered his relationship with him as students at the National School of Buenos Aires, the most prestigious public educational center of those years in Argentina and where future leaders emerged. politicians of the country: “Jorge had the need to demonstrate his Argentineness. Some called him Shigueki, and I understand that it would be his name in Japanese and he reacted by correcting: Jorge, as if there was something inappropriate, something that competed or conflicted with his Argentine identity. Those who called him Shigueki did not do it with an aggressive spirit, they did it in the same way that they called me by my name in Hebrew, Ioshua. There was something fascinating about the discovery that some of us had a unique cultural imprint, less common than the majority. Jorge's case always weighs on me because I can't help but think that perhaps he felt forced to risk , more than necessary, I think, and more than others, to gain a majority identity that seemed elusive to him.

As this testimony highlights, the story of Jorge Nakamura and the sixteen missing Nikkei belonged to a generation of young people who no longer had their parents' goal on the horizon, which was to return, one day, to the land of their origins. , Japan, because their time was “here and now”, where they were born and the echoes of the slogans of the French May (“ Freedom is not asked for, it is taken ” or “ Let's be realistic, let's ask for the impossible ”), the war in Vietnam or the death of Che Guevara hit like a breaking wave on the tide of young people who were in solidarity with the workers' struggles and believed in the realization of a New Man and with it, the dream of achieving a Better World...

Norma Inés Matsuyama wrote, when, like Jorge Nakamura, she attended the National School of Buenos Aires, but a few years later: “… Nineteen hundred and seventy-four was born with me, in this same dawn, sheltered by a truth, my truth, the one that so much I searched and, finally, I think I have found it .” She was a member of the UES (Union of Secondary Students), with Peronist traction*, and was 19 years old and eight months pregnant, when on April 8, 1977, she died, along with her partner Eduardo Testa, also a member of the UES, in a confrontation with armed personnel that depended on the Argentine Army and the Air Force.

In that country context, the Japanese community in Argentina was, for the most part, oblivious to the events that were occurring in the country. Luis Gushiken, brother of Carlos Horacio Gushiken, whom his relatives stopped seeing for the last time in February 1978, and whose remains were recovered by the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team, in mid-2002, reflected on those moments he experienced: “They lived ahead of their time . It was a time when sharing ideas and confronting power had become dangerous and any opposition was seen as disobedience or a lack of authority. You could perceive that even inside your own home, especially in a Japanese immigrant family, which had come from going through a militaristic regime and had become accustomed to living under strong discipline. I myself, as the eldest son, dedicated myself to doing my job in my parents' country house and was not interested in politics. And what I claim from my brother today is his right to live for an ideal. “His courage to fight for a more just society was as valuable as the sacrifice our family made to get ahead.”

*The Peronist movement was a mass political party that was born from the appearance on the political scene of General Juan Domingo Perón, a military man in his mid-40s in his position as head of the Ministry of Labor and Social Welfare, who promoted measures to favor the working sectors. This earned him enormous support from the popular sectors and great enmity from the business sector. He was president of the Argentines three times, a fact never repeated in Argentine history.

© 2016 Juan Andrés Asato