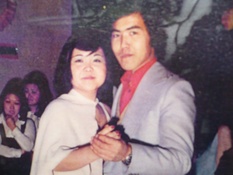

The faces of Seikichi Gushiken and María Arasaki in front of the family altar ( butsudan ) after lighting an incense next to the photo of the “appeared” son, Carlos Horacio, is one of the most powerful images of the documentary Silencio roto , which tells the story of the descendants of Japanese who disappeared during the last military dictatorship in Argentina (1976-1983).

Their looks summarize that long pilgrimage along an unexpected, winding and unknown path that the family had to travel, without ever imagining the meaning that the word missing would have for them. Only when they began to hear other names, more familiar because they were countrymen, did they understand what was happening to them.

The stories of Carlos Horacio Gushiken and Julio Eduardo Gushiken are the only two that to date allow us to glimpse with a different perspective the 17 cases of the Nikkei disappeared in Argentina. The remains of Carlos Horacio were found in 2002, buried as NN in the Parque de Mar del Plata cemetery, and that of Julio Eduardo, some years later during 2015, in the clandestine detention center known as El Banco , in the near the Riccheri Highway. In both situations the identification could be carried out thanks to the work of the Argentine Forensic Anthropology Team (EAAF).

The families of Carlos Horacio and Julio Eduardo lived in the southern area of Greater Buenos Aires, in the municipality of Florencio Varela, and the first was dedicated to growing flowers while the second was dedicated to planting fruits and vegetables. Although there was no direct family link between them, both young people attended secondary school at Santa Lucía de Florencio Varela (from which 10 students graduated who remain missing today) and were politically active in the PCML (Marxist-Leninist Communist Party). For neither of them there is precise information regarding the date and time of disappearance. But it is known that the PCML was the victim of a joint action by the security forces that began on December 6, 1997—throughout the country—and which was called Operativo Escoba, whose sole objective was to eliminate all its members. .

“ As long as he is missing, he cannot have any special treatment, it is a mystery, he is missing. It has no entity. He is neither dead nor alive. He is missing ,” said the dictator Jorge Rafael Videla, who was in power at the time. The “appearance” of the remains of Carlos Horacio and Julio Eduardo, however, re-signifies the value of the search. According to Carlos Somigliana, from the EAAF, the disappearance prevents a family member from beginning a possible mourning for the tragedy experienced. And he also added “identification remains an exceptional issue and the revelation of one case illuminates the possibility of other cases.”

In Japanese culture, and in particular Okinawan culture, from which 12 of the 17 missing Nikkei come, the “appearance” of missing children has a very high symbolic value. The 49-day mass marks the end of the period of mourning and the stay on earth of the soul of the deceased.

Luis Gushiken, Carlos Horacio's older brother, was able to celebrate it while his parents were alive:

“Although the pain of loss will always be there, they lived with great relief the time they had left before dying. For us, the union of family members to search for my brother was key because living in the countryside, far from many things, it was impossible to be close to any information. When in 2004 we held the 49-day mass at the club of the Japanese Association of Varela, many people from the community came and even members of the Japanese embassy in Argentina. And it was the first time that my brother's photo was placed on the family altar.”

Julio Eduardo Gushiken's family was also able to celebrate mass, which on this occasion was done under the Catholic rite, on September 20, 2015, in the San Juan Bautista Parish, in Florencio Varela. His mother, Victoria Kishimoto from Gushiken, along with her other five children (Mirta, Emilia, Roberto, Hugo and Graciela) were able to celebrate an emotional ceremony with family, friends and neighbors in the area.

For the anthropologist Carlos Somigliana, who was in charge of the identification of the two Gushiken, there may be more findings of missing Nikkei, but he clarified that “one cannot wait for the information to arrive, one has to go for it, and the logic is not to identify to a particular person, if not do it with all the people you can. And in that generality, illuminate the particularity . It is the dynamic of incorporating, adhering, adding and accumulating data. A very important exercise that is possible if the interdisciplinary work between the professionals involved in the research is done as a team.”

For the rest of the relatives who still do not know what and how the final fate of their missing persons was*, the search continues to be now and after so many years a more hopeful and less distressing “search”, perhaps. For example, Kamena Takara, daughter of Norma and Juan Takara (the latter, a professional accountant, political activist of the Peronist Party and disappeared on June 18, 1977), who, as she points out, searched and visited many places, travels this path. organizations, spaces, where they could inform him about his father, but in none of them he was able to integrate:

“I went to HIJOS, to Madres de Plaza de Mayo, but I couldn't find my place in the world. The word MISSING is very strong for me, I don't like cemeteries but if I knew that my father was there, or if they threw him into the river, no matter how strong the truth is, I could at least go there to leave him a message. flower".

That tension and anguish that the meaning of the word awakens is the worst of company. It hurts as much or more than the silence in which the relatives of the disappeared remained, especially those who already belonged to a second and third generation after that of the Issei —the pioneer immigrants—and who decided to raise their voices: “The The good part of all this is that what seemed like a perfect crime, carried out with all the power of the State, was not so perfect and this identification task becomes relevant for the family members because from the body found it is possible to begin mourning ," he explained. Carlos Somigliana of the EAAF.

“ The 30,000 missing were not 30,000 but 10,000 ,” were the unfortunate words of who until a few days ago was the Minister of Culture of the Nation, Darío Lopérfido, before his resignation. That statement generated a strong internal controversy in the current Government of President Macri (the Secretary of Human Rights, Claudio Avruj, publicly said he did not share that definition), added to the strong pressure exerted by Human Rights organizations, from Abuelas de Plaza de Mayo, Mothers of Plaza de Mayo—Founding Line—and even the Nobel Peace Prize winner, the Argentine Adolfo Pérez Esquivel.

But the forcefulness and firmness of the claims that have been made since the dictatorship to this party regarding the disappeared has its strongest and unquestionable support in the Trial of the Military Junta that led the country in those years of lead, by order of the then president of the Raúl Ricardo Alfonsín Nation, when on December 15, 1983 he sanctioned the decree ordering the prosecution of the three military junta. The trial had a great international impact and in neighboring countries such as Chile, Uruguay and Brazil, where similar situations were experienced, the repressors could never be brought to justice. Without a doubt, the most significant political event in Argentina in three decades of DEMOCRACY.

© 2016 Juan Andrés Asato