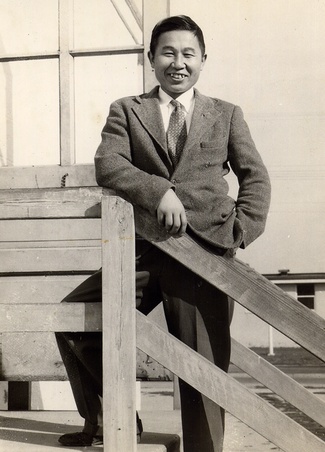

Akio “Lawrence” Nakagawa, a Kibei from the Sacramento Delta region, was interned at the Topaz, Utah camp. Answering the loyalty question “No-No,” he was transferred to Tule Lake, California, where he remained until the war ended, leaving in September of 1945.

When he was released from Tule Lake, he decided to head towards the Midwest to Minneapolis, Minnesota. There, he enrolled himself at the North Central Bible School, a school he had heard about through an Oakland-based Caucasian minister whom he met before his forced relocation into camp.

Akio’s train ride to Minneapolis was uneventful except for one incident. At one stop, a number of U.S. military soldiers came on board and made their way towards Akio who was sitting by himself. They asked him whether he was Chinese or Japanese. Afraid they would harm him, Akio answered Chinese, and the group left him alone. He was the only Asian on that train.

It was a cold day when he stepped off that train in Minneapolis. He was among two or three other Japanese Americans enrolled at the Bible School. He spent three years at this school which had a student body of about 400. He paid off his tuition by working odd jobs at a bakery, hotel, and grocery market. He recalled as a hotel bus boy he made 45 cents an hour. As a janitor at a bakery, he was paid 65 cents an hour.

After graduating from the Bible school, he did a lot of traveling, a period which he referred to as being a ronin*. When he ran out of money in 1948, he decided to make his way to Seabrook Farms in New Jersey where he worked for about 90 cents an hour, six days a week.

At Seabrook Farms, which employed a lot of Japanese Americans, he sorted out the bad vegetables that rolled down a conveyor belt. These included broccoli, asparagus, beets, and beans. Speaking in Japanese, he recalled those days as, “You’re on your feet the whole day, and you do the same thing, all day—It’s very tiring. Your arms begin to hurt, and the skin on your hand begins to peel off.”

Because the lack of ventilation made it extremely hot inside the plant, he remembered seeing a woman faint and had heard of other stories where women had fainted on the job.

He resided at the company dormitory and bought his supplies from the company-owned store. At the store, he recalled purchasing a lot of fresh fish and making it into sashimi.

About a year and a half later, he decided to explore other parts of America and made his way to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Since he didn’t know anyone, he dropped by the employment office where he found a job as a houseboy for the Knaur family. He recalled the pay wasn’t very good—about $20 a month, but more than two decades later, he would see the wife of this family get a presidential appointment on television.

When he thought he had saved enough money, he enrolled himself at the Bob Jones University, a seminary school in South Carolina. He noted that he was interested in doing missionary work, but his education was cut short after he ran out of money.

To make ends meet, he found a summer job as a taxi driver in Chicago. But he recalled having a lot of car trouble because minorities were given some of the junkiest company cars. In fact, one time, while Akio was driving a customer, his taxicab broke down in the middle of Chicago’s busy downtown intersection. Luckily, the customer was nice enough to get out and help push the car out of traffic. Akio couldn’t remember if he charged the Caucasian customer.

Soon after this incident, he quit the taxi driving business. But with very little money in his pocket, he couldn’t go back to school. As a result, he opted to head towards Miami, Florida, not only to find a job, but to explore a state he had always wanted to visit.

Again, since he didn’t know anyone in Florida, he headed for the employment office. He found a job as a houseboy with a widow named Mrs. Variel. He believes he worked six days a week for $30 a month. At this household, he remembered getting into big trouble over a fish incident. Akio, who was a big fish lover, had a craving for fish one day and decided to cook some up while Mrs. Variel was away. Needless to say, the fish odor lingered in the house, and he received quite a scolding.

Around 1951, Akio made his way back to California, but he didn’t head back to the San Francisco area. Instead, he went to Los Angeles’ Little Tokyo, where unlike Florida, there was a considerable Japanese American population.

In Little Tokyo, he lived in a hotel on Second Street, next to the Masago and found employment with Ontra Cafeteria. He worked at four branches of the Ontra Cafeteria—on Vermont, Crenshaw, Wilshire, and Highland.

Two years later, however, he decided to try his hands as a chick sexor because the pay was better. He attended a chick sexing school on Olympic Boulevard. The school, headed by a Japanese national, taught a new method which utilized sticking a light up the chicken’s orifice, according to him.

He was among 10 to 13 students, all of whom were Japanese Americans except for one Caucasian woman who was attending all the way from Arizona. After completing the course, Akio headed for Albuquerque, New Mexico.

Akio, however, soon found out that chick-sexing wasn’t what he imagined it to be. First of all, if the new technique wasn’t administered properly, it had fatal consequences on the chickens. Secondly, it was a seasonal job, available only in the winter. For this reason, he returned to Los Angeles, booked himself at the Allan Hotel, and was rehired at Ontra Cafeteria.

In the summer of 1963, he visited Wakayama, Japan for a miai ** (arranged marriage) and married Sugako Sakai. After a brief honeymoon, the couple returned to Los Angeles via San Francisco.

In Los Angeles, they lived in various apartments in the area which was then referred to as Seinan. Akio continued to work as a cook at a number of places including the City View Hospital in Lincoln Heights, which catered to a Japanese American clientele.

Meanwhile, Sugako who spoke no English and knew no one, was trying to adjust to a new culture in a foreign land. She held a number of jobs including that of seamstress, food packager, and parts assembler.

Then during the 1970s, like many Japanese Americans, the Nakagawa family migrated out of Los Angeles to the suburb of Gardena.

Notes:

* In Japanese legend, ronin were masterless—and thus migrant—samurai.

** Many Japanese Americans—particularly Issei, but also some Nisei—had their marriages arranged by their families via a go-between. This was a continuation of the marriage custom practices in the Japan of the time.

*This article was originally published in Nanka Nikkei Voices, Resettlement Years 1945-1955 in 1998. It may not be reprinted or copied or quoted without permission from the Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California.

© 1998 Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California