The most eminent of the five children of Aijiro and Nao Tashiro was certainly their son Aiji (pronounced “I. G.”). A writer, athlete, architect, and landscaper, he spent the better part of a half-century pursuing his work. Unusually for a Nisei, he spent almost his entire career living and working in the American South, far from the centers of Asian American population.

Aiji Tashiro, known as Tash, was born on July 6, 1908 in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, and spent his first years living with his brothers and sister above a cigar store in New Haven, where his father operated a restaurant. Midway through his childhood, Aiji movedwith his family to Seattle, where he first encountered other Nisei. He joined the Boy Scout troop at the Seattle Japanese Baptist Church, and became successively Wolf Patrol leader and Senior Patrol Leader. He attended Queen Anne High School, where he played on the basketball team. To supplement his family income, he worked summers in a fish cannery and as a strawberry picker. His parents were devout Presbyterians, and Aiji attended church with his family.

Following his graduation from high school in 1925, Aiji hoped to go to college, but his family could not afford to fund his studies. Instead, he took a job with the Great Northern Railway railroad. He was sent to Tye, Washington, to work with a maintenance crew in the old Cascade Tunnel. The crew, a polyglot team of ethnic Japanese, Filipino, Hispanic, and Hawaiian workers, lived in quarters made of abandoned boxcars.

Eventually, Aiji’s mother Nao contacted his uncle Shiro Tashiro, an esteemed faculty member at the University of Cincinnati. Shiro seems to either have found tuition aid for Aiji or provided funding himself. Whatever the case, in 1925, Aiji entered University of Cincinnati.

Once enrolled, as an architecture major in U. of C. engineering department, Aiji excelled in his studies. He took courses in such diverse subjects as medicine and Byzantine Art. He was also a champion athlete, whose speed and ball handling on the basketball court impressed observers.

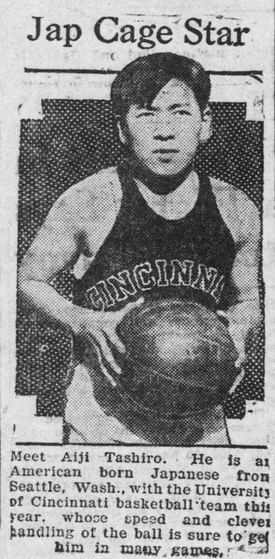

In 1927, Aiji was selected by coach Boyd Chambers for the university basketball team, the Bearcats. A newspaper article, with a photo of Aiji in basketball uniform, was widely distributed in the mainstream American press. He ultimately was placed on the reserve squad.

In order to support himself, Aiji took a job as the nightshift switchboard operator in a hospital. (It was a night job, and he would nap between calls—once a nurse played a prank on him by placing a rose in his hands while he slept). However, he soon became a patient himself: in his second year of college, he was diagnosed with tuberculosis in one lung. Aiji blamed the disease on his railroad work, when he toiled in tunnels and had to breathe in particles from passing locomotives. Aiji went through a complicated operation in which doctors collapsed one of his lungs, leaving it permanently reduced. He eventually spent a year recovering in a sanatorium.

By the time his health was restored, at the outset of the Great Depression, Aiji’s father had died and there was no money for him to return to school. During the next years, he worked as a domestic servant. According to one story, Aiji worked as a chauffeur for a physician, one Dr. C.B. Dotterer, who needed to visit a set of rural patients one summer, and who appreciated Aiji’s conversational skills.

Eventually, when the summer ended, the doctor encouraged Aiji to attend school and lent him $500 towards that purpose. He reenrolled at Cincinnati, though his athletic career was ended by his health crisis. He graduated with a BS in Landscape Architecture in 1933.

Following his graduation, Aiji became a professional landscaper in Cincinnati. His first assignment was to supervise the reconditioning of the William Henry Harrison Memorial State Park in Ohio, with financing from the New Deal-era Civil Works Administration. He and architect Stephen Wardwell were put in charge of forty men, including technical engineers. (Tashiro’s plan to refurbish and modernize the classical design of the tomb of the 9th president of the United States attracted criticism from locals, giving him his first widespread publicity!)

From 1934 to 1936 he served as landscape architect for the Ohio Historical and Archeological Society and the Cincinnati Public Recreation Commission and the city Park Board. From 1936 to 1938 he ran a private practice in Cincinnati, as a partner in the firm of Tashiro & Parker. During these years, Aiji worked on projects for Dr. Joseph Freiberg, Mr. and Mrs. Harry Lowenstein, Mr. and Mrs. Harold Comey, and others.

One of the firm’s most prominent jobs was landscaping the Rauh House, a notable International Style residence designed by architect John W. Becker and built in 1938. The same year, he produced a garden for the residence of Joseph Work with an elaborate wall garden whose image was featured in the pages of the Cincinnati Post. In 1936 he married his first wife, Isobel Hess, a white woman from Ohio.

Even as he established himself as a landscape architect in Cincinnati, Aiji actively pursued a career as a writer. Curiously, unlike his brother Ken and sister Aiko, he did not start off writing for the Nisei press. Instead, he worked as a stringer, hired by newspapers to do local reporting. According to family sources, as early as his youth in New England, Aiji would keep a calendar of public meetings in the small communities where he lived, and would attend and report on sessions of town councils, school boards and court hearings, as well as occasional local high school football games.

His first regular assignment was as a correspondent for the University of Cincinnati’s student newspaper, the News-Record. During his student days, he began selling comic material to the popular humor magazine College Humor and to other publications. One of his short stories was republished in Rafu Shimpo.

In summer 1934, he achieved a major coup when he published an extended article, “The Rising Son of the Rising Sun,” in the nationally-based magazine New Outlook. It was the first time that a voice from the community had appeared in a nationwide publication. The article was a slightly fictionalized autobiographical essay on the problems, experiences, and aspirations of the Nisei generation.

The author described himself as born in the second story of an apartment above a cigar store in the college town of New Haven, Connecticut. Since his birth, he added, his entire life had been spent in the east, with the exception of a short visit to the Pacific Northwest, where he was as surprised as any American by the life and manners of the second generation Japanese. The author felt completely at home neither with the Nisei he met on the West Coast, nor with the Caucasian students with whom he attended college, though he had managed to persuade them that his life was no different from theirs.

With a comic touch, the author expressed his frustration over the stereotyping and discrimination that greeted him as a Japanese American when he graduated from university and sought employment as an engineer. He was successively offered work as a valet, ukulele instructor and seller of miniature gardens. As he recounted, he finally was invited for a more formal job interview:

The president of a large corporation ran his eyes over my five feet five, slowly. He took in my Bostonianisms, my Arrow shirt, my Hart Shaffner and Marx suit. I congratulated myself on being one Oriental who had no perversion toward blue serge suits and yellow shoes. ‘I think you’ll do,’ he said slowly. My heart jumped. He had summoned me out of a clear sky to come see him at his office, and here I was already hired!

“What do you weigh stripped?” he asked me next. A trifle puzzled, I told him. ‘We’ll bill you as Togo,’ he added. And then I learned that he had a hobby of promoting tyro wrestlers. He was sorely disappointed when I told him I sought laurels in other fields.

“The Rising Son of the Rising Sun” was heavily publicized in the West Coast Nisei press, where Aiji’s siblings were already well known. Leading Nisei litterateur Mary Oyama Mittwer referred to the essay as “one of the finest pieces of Nisei writing ever printed.”

In addition to being insightful on the dilemma of the Nisei, Mittwer noted, “Our American friends were astonished to learn that a Japanese American could write with such fluent talent and posses such a remarkable vocabulary.” Bill Hosokawa would later write that it was “an articulate and moving job of writing, tinged more with bewilderment and sadness rather than bitterness.”

Fresh from this success, Aiji threw himself into freelance writing. According to family lore, he acquired a literary agent, and at some point drafted a novel, which he was unable to sell. Meanwhile, he made a specialty of short stories. One short story appeared in Kashu Mainichi. Titled, “A Man Named Mallory,” it was the story of a man with a bright future and his subsequent degradation.

In the next years, he began producing fiction for mainstream newspapers: Aiji was the only Nisei in the prewar period who managed to sell articles consistently to national magazines and syndicates.

In January 1938 he sold a story, “The Girl he Loved,” to United Feature Syndicate, which then ran in dozens of subscribing newspapers. It was a piece of romantic fantasy about a young woman who managed to touch the heart of a philanderer. In the following months, he sold two more stories, “Rendezvous” and “It Wasn’t Hate,” to the United Features Syndicate.

In 1940, he followed with a final story, “The Moon is Full,” a story of intrigue among international secret agents. These stories were all “mood pieces,” inspired by the works of the writer O Henry, whom Aiji admired. They set an atmosphere and lulled readers before shocking them with surprise endings.

During these years, he also contributed to the literary sections of the West Coast Nisei press. In summer 1933, following graduation from University of Cincinnati, he contributed a set of his News-Record columns, “College Meanderings” to Kashi Mainichi.

He also experimented with verse. In 1937 he won an annual Christmas Poem contest sponsored by the Cincinnati Post newspaper. In 1938, he published a pacifist poem, “To the Living,” which included this moving verse:

Harken above, my living brother.

What day is this that cannons wait?

You say the moon has stilled this madness.

For one short night has quenched all hate?

Ah well, your thoughts from deaths of glory

Drift to peace beneath pale stars.

Were it that my own eyes while seeing,

Saw the emptiness of wars.

In a published letter to a friend written during this period, he described himself in minute and colorful terms:

Introvertic—dislike noise—love solitude—outdoors—athletics. Reticent with women for, oh so long, before I say more than “hello.” Own a Plymouth, smoke Chesterfields, like plain collar attached shirts, scotch grain shoes, hate beer, have too much pre-college idealism. Baptist because my dad sent me there, 27 last July, dance most horribly. Never been in Cal, much too independent and outspoken, pity ignorance, hate stupidity, detest provincialism, love strife, work, fight, difficulty. Have, according to others, a humor Voltairish and Milne, cherish illusions. horribly sensitive but getting over it. Draw, paint, write, and can put the spirit of Michelangelo into a pot boiler. Am hell on writing letters. Amen.

To be continued... >>

© 2024 Greg Robinson