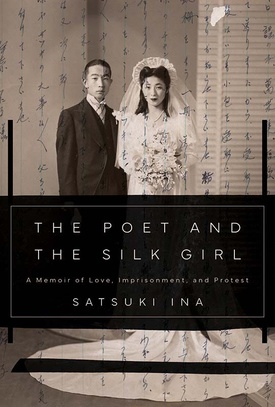

It’s an incredible honor for me to speak to Dr. Satsuki Ina. Ina is a Sansei activist, therapist, community healer, and now memoirist with The Poet and the Silk Girl: A Memoir of Love, Imprisonment and Protest (Heyday, March 2024). The book is a family memoir using various archives and documents of her parents during World War II as they navigated wartime hysteria, imprisonment, racism, and resistance. She was generous to share her time with me to speak about two of her current projects that have deep family connections: her new memoir, and the memorial courtyard under construction in Bismarck, North Dakota at the United Tribes Technical College.

* * * * *

TN: You’ve created so many things—documentaries, activist groups, healing circles—and now a family memoir. Congratulations on the forthcoming publication of your book! What have been the most challenging parts of the writing process?

SI: The most challenging part of writing this book was all the ways the story was at the outset, “out of reach” for me. First, many of the letters my parents exchanged were written in Japanese and much of it was censored. To tell the story as accurately as possible, I had to find a highly gifted translator who could not only capture the essence of the messages in the letters, but also capture the unspoken nuances expressed from a Kibei perspective in terms of values and priorities.

Secondly, due to shame and suffering, my parents shared very little about the prolonged emotional trauma of their incarceration. Once they passed away, not unlike other descendants, I was left with a massive collection of confusing and conflicting pieces of an intergenerational puzzle. Only after facilitating close to a hundred “Children of the Camps” group therapy sessions, was I able to knit together a coherent autobiographical narrative for others and myself.

And third, the suppression of documents and distortion of incidents within the prison camps by government officials had led to misleading and false accounts about individuals and organizations in the prison camps. Thankfully, over time the work of scholars and academics including Barbara Takei and Art Hansen began to uncover and challenge the false government narratives, specifically about “dissidence as disloyalty” in the camps.

TN: How about the most wonderful parts of the writing process?

SI: Writing does not come easily for me so it’s hard to think about the “wonderful” parts of the writing process. Perhaps the pain of uncovering a deeply buried family story is what made the process so torturous. Lifting up and out, heavy shovelfuls of the past mired in cloudy truths and lies was more burdensome than the actual bones of the story I discovered. What was actually, wonderful was laying the shovel down.

TN: One of your current projects includes fundraising for the Snow Country Prison Memorial at the United Tribes Technical College. Can you talk about how your involvement in the project started?

SI: My involvement in what would become, twenty years later, the Snow Country Prison Memorial Project began around the year 2000 when I flew to Bismarck, ND on a location scouting mission. The documentary film, From A Silk Cocoon (now streaming on Amazon) was to be the film version of my family story.

My father had been taken from us in the Tule Lake Segregation Center and interned at the Ft. Lincoln Dept. of Justice Internment Camp along with nearly 2000 other Issei and Kibei men unjustly designated as enemy aliens. That site is now the United Tribes Technical College, a private tribal land-grant community college in Bismarck, ND.

Today, College administrators and staff have joined with Japanese Americans (including descendants of former internees) to create a memorial on campus to recognize and honor more than 1,100 Issei (first-generation) and 750 Nisei (second-generation American citizens) who were incarcerated at the camp.

The memorial will symbolize the fracture of the spirit, of the family, the community and the profound healing intrinsic to working in solidarity to repair what was broken by hate, racism, and white supremacy. Here we will name the men who were held prisoners during WWII and we will tell the story of the Native people who have survived genocide and managed to thrive through hard work and education.

TN: What draws you especially to working on this memorial, in addition to your family history connection?

SI: First of all, this memorial project would never have been possible without the generous offering by the folks at the UTTC to provide land, a precious commodity for both the Native people who were forced off the land that belonged to them and to the Japanese Americans who were not allowed to own the land on which they toiled. This collaborative memorial project will commemorate the story and the site that has been little known in the US and even to the Japanese American community. An inspirational offering to memory and to justice, we are grateful to be in solidarity with the Native American leaders and administrators at UTTC.

TN: The Snow Country Prison Memorial is now seeking fundraising support from the Nikkei community. Can you talk a bit more about these efforts?

SI: This memorial designed by the renowned social justice memorial architects from MASS Design Group will include a courtyard surrounded by the brick buildings where Japanese American internees were held during WWII. Two walls that stand apart depicts the “kintsugi” Japanese ceramic art process that repairs fractured pieces of ceramic with gold flecks mixed with the glaze, giving the piece historic meaning and value.

Between the walls that will each be inscribed with the stories of the two communities will be a walkway where people can read the names of internees, learn the historic timeline of the Native people in the North Dakota area. I like to think of the people who walk between the two walls as the “gold” that heals and transforms.

Though we have raised a significant amount of support, including in-kind donations, we are still seeking close to $250,000 in funding through this next year. We hope that our Japanese American community will join our efforts.

TN: What are your hopes for the memorial? What kind of preservation or cultural or memory work do you hope it will achieve?

SI: A significant element of the memorial will be the Drumming Circle where both Native drummers and Japanese American taiko drummers will be able to bring to life the untold stories of sorrow, loss, humiliation, anger, survival, vindication, and hope.

The walls will provide the concrete stories and history, but the gathering of people for pilgrimage, ceremony and prayer will be a reminder that standing together in solidarity, reaching hands across the divide that oppression creates, is how we must fight for each other and together for justice and humanity to prevail.

North Dakota is distant for many of us living on the coasts of the US, yet when we travel and gather at the Snow Country Prison Memorial, a powerful healing can take place.

To learn more about the Snow Country Prison memorial, watch this video or visit the memorial website (https://tinyurl.com/SnowCountryInfo).

To donate to the memorial construction, visit UTTC Fundraising (https://tinyurl.com/SnowCountryDonate). Be sure to select “Snow Country Prison Japanese American Memorial Courtyard Project” in the “Designation” menu.

For more updates and details, follow the project team on Facebook (“Snow Country Memorial” page) and Instagram (@snowcountrymemorial).

© 2024 Tamiko Nimura