This series narrates the history of the Hyoshiro1 and Fujiye Hirai family, especially focusing on the two sons, Shig (Shigeru) and Miki, both of whom have been very active members of the Japanese Canadian community in Vancouver, BC (British Columbia). When Shig and Miki were children, the Hirai family were among the nearly 4000 Japanese Canadians exiled2 to Japan at the end of World War II.

The first chapter briefly summarizes the Hirai family background and their life in Canada before and during the internment period until their decision to move to Japan after the war. Subsequent chapters will describe in more detail their life in Japan during the period immediately following the war, their return and readjustment to Canada in the late 1950s, and finally Miki’s life after retirement and his vision for the Japanese Canadian community going forward.3

* * * * *

Family Roots

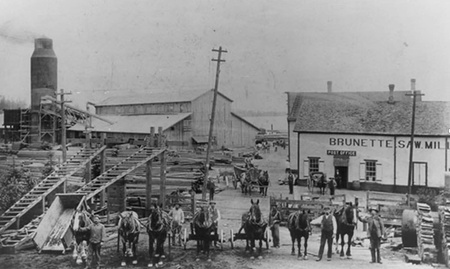

Fujiye’s father, Sanya Fujino, moved to Canada in 1893 from Oyabu, a small village on the shore of Lake Biwa in Shiga prefecture.4 He found work at the Brunette Sawmill in the Sapperton area of New Westminster, BC. Soon he became one of the “bosses” at the mill and was put in charge of all the Japanese laborers. He also owned a boarding house in Sapperton which accommodated about 20 single laborers, and the family looked after the Japanese men who worked at the sawmill.

There were five children in the Fujino family. Fujiye was the second oldest child with two brothers and three younger sisters. She did not have the opportunity to go to school as she had to stay home doing laundry, cooking, cleaning, and other household tasks in order to help take care of the Japanese men living in their boarding house. However, at age 15 she got her barbering license. Miki explains:

My mother’s job was to be home, so she never went to school here in Canada. I guess she grew up cleaning people’s laundry and cooking and whatever to help the twenty people living in the boarding house. That was her life until maybe she was around 15 or so. Then she went to barbering school to learn the trade of cutting hair for men.5

Hyoshiro’s father, Sekizo Hirai, moved to Canada, in 1906 from Tsuchida, a small village located a few kilometers southeast of Hikone, leaving his wife and children in Japan. He found work on a farm and by 1920 had saved enough money to buy a quarter section of land near Mission, British Columbia. Miki is not sure what kind of farming he was doing there, but thinks it was likely strawberry farming as that was what many Japanese Canadian farmers in the area were engaged in at the time.6 He had four sons, of whom Hyoshiro was the second oldest, born in Tsuchida in 1907. In 1922, Hyoshiro went to Canada to join his father and worked mainly in the sawmills.

Hyoshiro met Fujiye Fujino through the traditional Japanese custom of arranged marriage. After their marriage in 1936, Fujiye continued to work as a barber in Vancouver. Later, her skill at barbering would play a critical role in the economic survival of her family during the internment period, their time in postwar Japan, and again after their return to Canada in the late 1950s. Their first son, Shig, was born with the assistance of a midwife in a home near Powell Street on September 9, 1937.

Hyoshiro’s father, Sekizo Hirai, returned to Japan at some point before the war, leaving Hyoshiro in Canada. It is not known exactly when or why he went back but Miki thinks he intended to stay only temporarily as some going back and forth between Japan and Canada was common. Sekizo owned a farm near Mission, which would have been a good reason for him to intend to return to Canada, so it is possible he just happened to get stranded in Japan by the war.

Start of the War, Uprooting, and Internment

When the war started, Fujiye Hirai was working in a barber shop on Main Street. At that time, things were rapidly becoming worse for the Japanese immigrant community in Vancouver. Miki explains:

She didn’t know anything about war... The war came, and she noticed a lot of changes … At the barbershop they were calling her names. She didn’t quite understand what it meant, because even the other Orientals were calling her “Jap,” and they were spitting on the windows as they walked by, and suddenly hardly any customers walked in. Nobody dared to walk in — they were scared to walk in.7

Under normal circumstances, Hyoshiro Hirai, as the oldest surviving son of Sekizo, would have been heir to his father’s land. However, this expectation was overturned by the start of the war. The Hirai and Fujino families, like other Japanese Canadians, were soon uprooted from their homes and sent to be incarcerated in internment camps.

As is well known, all the businesses and properties of the Japanese Canadians were confiscated by the Canadian government and, contrary to the government’s promise of safekeeping until the end of the war, were sold off at a fraction of their value. In this way they lost everything they had worked so hard to build.

Miki explains about his grandfather Sekizo’s land, “It had been all paid up when they took it. Within about ten days they turned around and sold it to somebody else… for around two thirds of the (original) price.”8 Miki speculates Sekizo probably never realized his land in Canada had been sold off by the government as years later he gave the deed to Miki’s parents when they moved from Japan back to Canada in the late 1950s.

Even after the war ended, Japanese Canadians were forbidden to return to their homes on the west coast until 1949, and that prohibition may have been enough reason for Sekizo to resign himself to staying in Japan permanently where he also owned a considerable amount of land.

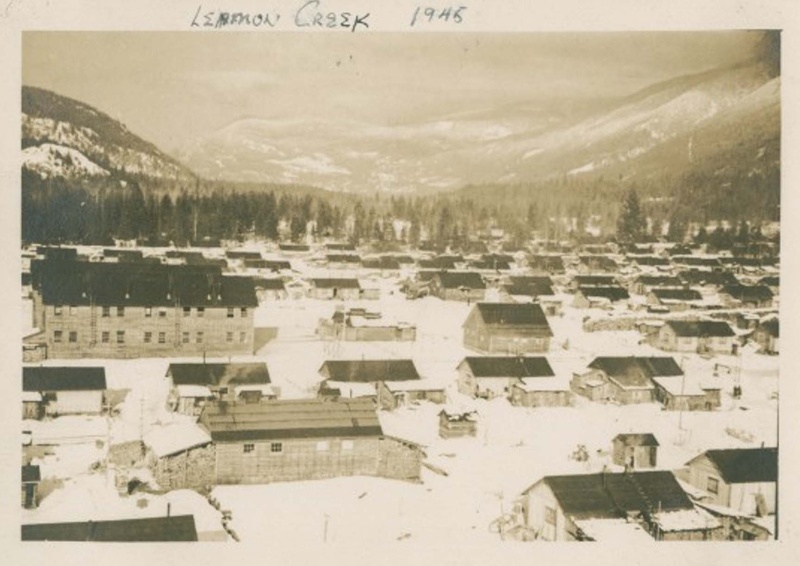

The Hirai family was sent to the internment camp at Lemon Creek in the interior of British Columbia. Hyoshiro Hirai went ahead of his family and helped in the construction of the small rows of houses there where the Japanese Canadian families would be forced to live during the war. When his family joined him, they shared a small house with a cousin’s family. Miki was born in the hospital in nearby Slocan on May 22, 1944.

Despite the deep trauma of the uprooting and loss that the adults were experiencing, they made the best they could of their terrible situation and endeavored to shield their children from their pain and give them a normal happy childhood. As a result, most of the children had mainly happy memories of the internment camps. Shig recalls that, regardless of the difficulties the adults were experiencing, for him as a child “it was the best time of my life.”

While Miki was too young at the time to have memories of the internment camp, he does recall his mother talking about her life in Lemon Creek. Ironically, even as an adult, despite the heartbreaking loss of her family’s properties and livelihoods, and despite the extremely cold weather and lower standard of living at Lemon Creek, in some ways life there turned out to be better for her than the difficult situation she had left behind in Vancouver, and like her oldest son Shig, she remembered this period as the best time of her life. Miki explains:

Surprisingly… she said that was the best time of her life… it was the first time she didn’t have to work. Also, she could use her barbering skill there so was very appreciated by others. That was where she learned to sew for the first time… Not only that, but in the camp they had a school, they had a church, they had a kitchen, and they had it all organized. And they built various amenities including a Japanese bath house, and so on. So, she enjoyed many things now that she was finally learning something.9

After internment, Miki’s father made the difficult decision go to Japan instead of moving east of the Rockies because his father, who had previously moved back to Japan and was still there, asked him to do so. Miki explains:

What I heard from my parents was that his father told him to come back to Japan. My father was the second son… but the first son had perished in the war. The third son had died from illness. The fourth son was on a Japanese submarine during the war. According to what I heard, the submarine had a mechanical problem and couldn’t surface. Eventually they were able to surface, but the war had just ended, and he got caught by an American boat. He became a POW and got sent back to Japan.

The next chapter will focus on the life of the Hirai family in postwar Japan.

Notes:

1. He was also sometimes called Heishiro due to variation in the reading of the first Chinese character of his name.

2. There is some difference of opinion regarding the most appropriate term to describe the movement of these Japanese Canadians to Japan after the war. The term “deportation” has been rejected on the grounds that many of them were either Canadian-born or naturalized Canadian citizens and the term “deportation” implies that they were not Canadian citizens.

The issue is further complicated by the fact that they were not physically forced to leave Canada but were prohibited from returning to their former homes on the west coast and then given a very difficult choice either to relocate east of the Rocky Mountains or go to Japan. Many ended up choosing the latter as the lesser of two evils, often to their regret later.

“Exile” has become the most widely accepted term although not unanimously agreed upon. For example, Miki Hirai has indicated to the writer that he did not see his family as “exiles” and prefers the term “Kika” which more broadly refers to Japanese Canadians who went to Japan and later returned to Canada.

3. Most of the content of this series is based on personal communication with Miki Hirai, his brother Shig Hirai and Shig’s wife Akemi Hirai consisting of three audio-recorded interviews (August 22, 2022 and August 13, 2023 with Miki Hirai; August 23, 2023 with Shig and Akemi Hirai). These interviews will not be cited further. Sources other than these will be cited.

4. Oyabu was later merged into the city of Hikone.

5. Hirai, M. (June, 2023) “Okaeri おかえり— Return from Exile: All Paths Lead Home,” Nikkei Images, Volume 27, No. 3, p. 6.

6. For a good description of the kinds of agriculture the Japanese Canadian farmers in this area were engaging in, see “The Fraser Valley: The Farms They Left Behind” (Oct. 8, 2014) by Regina Japanese Canadian Club Inc.

7. Hirai, M. (June, 2023) pp. 6-7.

8. Ibid.

9. Ibid, p. 7.

© 2024 Stanley Kirk