100 people cried after hearing the Emperor's radio broadcast, and the windows fogged up.

On August 15th, 78 years ago, at Sao Paulo Girls' School (now Akamagaoka Gakuin) in the city of Sao Paulo, female students with tense expressions on their faces waited with bated breath for the Emperor's surrender broadcast to begin.

"At the request of teacher Akama Michihe, about 100 students and staff gathered in the cafeteria and listened to the Emperor's surrender broadcast on a small shortwave radio. Everyone had been secretly studying Japanese during the war, and naturally assumed that Japan would win the war. But when we heard the broadcast and realized that Japan had lost, we all burst into tears. The windows had been shut tightly to stop the sound from the radio leaking out, so the glass became fogged up with our sobs and tears."

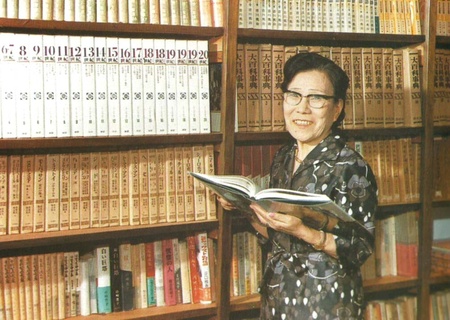

I interviewed Mayumi Mizukami (93 years old, born in Aliança 3) on June 7. Scenes like this were unfolding at the school, located on Vergueiro Street in the city of São Paulo, at the end of the war.

Mizukami was the third child born in the Third Alianza and was 15 years old at the time. "After I finished the third grade of elementary school, I worked as a farmer, but at night, my mother taught me Japanese strictly and I read Japanese books," he said. In February 1945, just before the end of the war, he moved to São Paulo and studied at Akama.

She vividly recalls, "Mr. Akama said to us, 'The war is over. There's no need to hide, so open the window and cry as much as you want,' and then we started crying loudly."

During the war, Japanese language education was banned, but it continued in secret in some places. Right after the end of the war, until the struggle over who would win or lose began, almost everyone in the Japanese community believed that Japan had won the war. After the broadcast of the Emperor's surrender, people were divided into those who believed that Japan had lost and those who did not.

A similar problem occurred at Akamagaoka Gakuin at the time. There were teachers who believed in victory, such as Shingo Shibuya, who taught history and geography, and teachers who believed in defeat. They split into two groups and caused a commotion, involving parents and students.

Mizukami recalls, "Akama-sensei was in a difficult position and thought, 'I have to endure this somehow,' so he temporarily stopped teaching Japanese, which he had been continuing even during the war, and in the end, without taking sides, he fired both teachers. I think it was a difficult decision."

When I interviewed Antonio Kohei Akama (then 80 years old, second generation American) on January 29, 2010, he told me, "I read American magazines like Life, and I knew that Japan's wartime situation was bad even during the war. But there were also teachers at school who were on the winning side, and the parents' association got involved and the school was divided into two factions, and my mother had a hard time mediating between them."

Kohei's wife, Euza's father was Sunao Baba, the founder of the Tokyo Colony. He was from Nagasaki and his grandfather had been a doctor. He ran a hospital in Nagasaki, but left it to his younger brother for a few years and went to Brazil to help Japanese immigrants suffering from malaria, and founded the Tokyo Colony. However, the war began and he was unable to return home.

After the war, the Baba family received threatening letters from hard-liners on the winning side at their home in the Tokyo colony, saying, "Take a bath and clean yourself up before waiting." Thinking that it was dangerous to be around Japanese people, they had the sad experience of fleeing to Piracicaba, where there were almost no Japanese people at the time. Euza said, "At the time, I was scared when I saw Japanese people."

Everyone believed in Japan's victory, but the education world was divided immediately after the war. Akama Gakuin began to walk the path of an educational institution on the side of the recognition faction. The trigger for this decision was probably the severe pressure from the authorities during the war.

Founded in 1933, the number of students increased due to the outbreak of war.

According to the "50th Anniversary History of the Akama Gakuin Foundation" (1985, Akama Gakuin Foundation), the school experienced a period of great hardship during the war.

Akama Juji and his wife Michie came to Brazil in 1930 and opened a sewing school on Conselheiro Furtado Street in the Liberdade district in 1933, which they soon renamed the São Paulo Sewing School. In the "Founding Address" of the inaugural issue of the school's internal magazine, Gakuyuu, published in March 1934, two years after the school's founding, Akama Juji, the principal at the time, wrote the following about the motivation for opening the school:

I would like to briefly explain the motivation behind us opening this institute. When I first left for Japan, I had the vague idea of visiting and studying a part of the fishing industry in the country, as I was majoring in fisheries, and having my wife study dressmaking at the same time, and then returning to Japan in about five years.

However, when I visited the country and met the girls who lived in the outback and were working hard without enjoying any cultural benefits, I felt a desire to do something for those girls, despite my own limited knowledge and talent. Fortunately, my wife had been involved in girls' education and I also had some experience in the education business, albeit for a short time, so we both felt the desire to try to start this business together.

Then, in September 1933, he founded what was essentially a modest school in name only (it might be more appropriate to call it a cram school).

In September 1935, it became a practical girls' high school, and in 1937, it was officially recognized as a private school and became the Sao Paulo Girls' School. In 1941, it moved to a school building on Tamandare Street. In December of the same year, Pearl Harbor was attacked.

[1942] From January 15 to 27, the United States led the Pan-American Foreign Ministers' Conference in Rio, where 10 South American countries, excluding Argentina, resolved to break off economic relations with the Axis powers. The Brazilian government announced that it would break off diplomatic relations with the Axis powers, including Japan, on the 29th, closing the embassies and consulates of Japan, Germany, and Italy, and targeting the people of these three countries as "enemy nationals" and cracking down on them.

In response to this, on January 19th, the São Paulo State Security Bureau issued a set of rules for cracking down on enemy nationals. The distribution of documents written in Japanese, the use of Japanese in public, and travel and relocation without a permit were all prohibited. Interestingly, Akama saw an increase in students enrolled in the home economics department at the school due to the closure of local Japanese schools. Over 100 Japanese students gathered there every day, drawing the attention of the Brazilian authorities.

*This article is reprinted from the Brazil Nippo (August 15, 2023).

© 2023 Masayuki Fukasawa