As the hidden history of postwar Japan

Photographer Tsuneo Enari, who has captured things that postwar Japan has forgotten, published "Brides of America" in 1981, a collection of portraits and interviews depicting the candid lives of women who had married American soldiers and gone to America. This book caused a stir, bringing to light an era and people that had previously been overlooked by the media.

Enari has faced the postwar lives of people who in some way bore the negative legacy of Japan's wartime legacy. He has since traveled to China to interview and photograph Japanese orphans left behind in China after the war, capturing their postwar experiences and real situations through his work.

Then, 20 years after interviewing those first brides, I interviewed them again and compiled "Bride's America: A Landscape Through the Years 1978-1998," she said, she shed light on what it means to be Japan, to be Japanese, and to be Nikkei amid the passage of time and the changing of generations. Last year, a new edited version of "Bride's America" and "Bride's America: A Landscape Through the Years 1978-1998" was published by Ronsosha (Chiyoda-ku, Tokyo) as "Bride's America [Complete Edition]."

We introduced the two “bride”-related works and the world they create in the 22nd issue , but we visited Enari at his home in Sagamihara City, Kanagawa Prefecture, to talk to him again about the background to the creation of these works.

* * * * *

--When you first started reporting, how did you go about visiting "brides"?

Enari: In October 1978, I rented a one-room apartment in Gardena, a suburb of Los Angeles, and used it as a base to search for and visit brides. I drove about 35,000 kilometers from San Francisco to San Diego in a year and met about 120 people in total.

When I visited, some people didn't want to talk much, and sometimes I was turned away, but I didn't regret the effort. I went around wanting to know what kind of people I could talk to and what kind of stories I could hear from them, so I went around visiting brides and met one bride, who introduced me to another person.

What was your first impression there?

Enari: The first thing I noticed was religion. After all, these women who left Japan had no one to rely on, so they had no choice but to rely on something. That was religion, and I could say they were relying on some kind of religion 100%. It was connected to faith. The most common religion was the NSA (Soka Gakkai).

Some people practiced other religions, such as Catholicism, but most were new religious movements.

--In "American Bride," the words they spoke are recorded exactly as they were spoken by the women, but I think this was one of the things that attracted readers.

Enari: Their language is a mix of English and Japanese. They use Japanese as a base, but English is their everyday language, so they use conjunctions and other simple English words here and there. This was refreshing to me, and I also felt sad.

But at the same time, there was something about those words that drew me in. They conveyed a richness of humanity, and the feelings of women who are often discriminated against in Japan. So I introduced those words in the book as they were, without adding my own subjective opinions, and it seemed to have the effect of honestly expressing the feelings of the bride.

--What were the reactions to the book when it was published?

Enari: I thought it would be better to add words as well as photos, so I compiled the bride's words, leaving the long ones as they were, and arranged the photos and words. This year, it was nominated for the Soichi Oya Non-Fiction Award. Hisashi Inoue also featured it in the newspaper. There was value in the way it was brought to attention as information.

--What were their thoughts about Japan?

Enari: The Japanese spirit and patriotism are stronger in people who have experienced hardship. None of the people I interviewed felt abandoned or said they would never return to Japan. Some even made sushi and waited for me when I visited them. Such actions are connected to their pride in living as Japanese people. Their strong sense of being Japanese was also reflected in the way they raised their children.

When I visited the same bride 20 years later, I learned that her expectations for her child were linked to her patriotism, so I wanted to share with Japan, where there were people who once looked down on them, how their child (who is second-generation Japanese), was growing up.

The more oppressed a person is, the more they think about their home country. Chinese war orphans are exactly the same. These are children who were left behind after the Soviet Union invaded Manchuria. I visited these war orphans over a period of four years. They don't know who their parents are, but they are very eager to meet Japanese people. When I visit them, they are eager to get my business card. They want to connect with Japanese people in Japan. It's an expression of their desire to return to Japan.

INTERVIEWER How did you feel about your relationships with and education of second-generation Japanese children?

As for Enari 's children, I felt that they were proud to be Japanese mothers. They seemed to have been taught etiquette that Japanese people seem to have forgotten, and they seemed to be well-disciplined as mothers.

In Japan, it seems that the original Japanese culture has been forgotten after the war, but on the other hand, the bride's children seem to have been raised in a good way. There is nothing servile about them. This may be due to the influence of American society.

--Because their husbands were in the military and they were transferred frequently, it must have been difficult for them to connect with the community?

Enari: Yes, that's true. However, there was a connection with the same hometown. For example, San Diego is a port of call for the Seventh Fleet, and is connected to Nagasaki and Sasebo, so many brides are from Nagasaki. There is a Nagasaki Prefecture Association there, and brides can interact with each other. I was once invited to a party, and their husbands were also there, and we had Japanese food.

Japanese Self-Defense Forces ships dock in San Diego, and Naomi Campbell, whose husband was in the Navy, said that while she had never cried when her husband's ship departed, she now sheds tears when the Japanese Self-Defense Forces ship docks in San Diego and leaves.

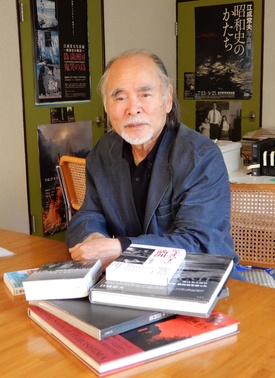

Tsuneo Enari Born in Sagamihara, Kanagawa Prefecture in 1936. Photographer and Professor Emeritus at Kyushu Sangyo University. Joined the Mainichi Newspapers in 1962, covering events such as the Tokyo Olympics in 1964 and the signing of the Okinawa Reversion Agreement in 1971. Left the company in 1974 to go freelance, and moved to the US in the same year. While in New York, he met "war brides" who had married US soldiers and crossed the ocean, and in 1978 he visited them in California to photograph them. Since then, he has used his photographs to speak for those who were at the mercy of the Asia-Pacific War and had no voice, and continues to question the Japanese perception of modern history. His photo books include "One Hundred Portraits" (Mainichi Shimbun, 1984, Domon Ken Award), "Phantom Country: Manchuria" (Shinchosha, 1995, Mainichi Art Award), "The Bride's America: Landscapes of Time" (Shueisha, 2000), "Hiroshima All Things" (Shinchosha, 2002), "The Island of Demons' Cries" (Asahi Shimbun Publications, 2011), "The Atomic Bombings: Hiroshima and Nagasaki: Proof of Life" (Shogakukan, 2019), and more. His books include "The Bride's America" (Kodansha, 1981, Kimura Ihei Award), "Xiaohai's Manchuria" (Shueisha, 1984, Domon Ken Award), "Scenes of Memory: Ten Hiroshimas" (Shinchosha, 1995), and "Showa Reflected in the Lens" (Shueisha Shinsho, 2005). (See Ronsosha's profile) |

© 2023 Ryusuke Kawai