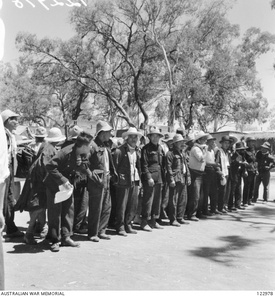

Japanese Americans and Japanese in internment camps

-- In After Darkness, there are characters of both foreign and Japanese descent, such as an Australian of Japanese descent. They are put in the same camps as the Japanese, but what was their position at the time? Were they in conflict with the Japanese?

Christine Piper (CP): I spent a lot of time doing research at the Australian National Archives , where the military records are kept. And as I'm half Japanese, I was interested in the reports about mixed race people and Australian-born Japanese internees. I really empathized with them. They were caught between two cultures and not welcomed by either.

Despite being proud Australians and eager to risk their lives to fight for their country, they were arrested and interned on suspicion of sympathy for the Japanese.

My research has shown that most mixed race and Australian born (Japanese) internees were sympathetic to Australia rather than Japan, they were outsiders in the camps, they were treated poorly by the Japanese camp leaders (e.g. they were made to do menial tasks like cleaning toilets), they were forced to swear allegiance to the Japanese Emperor, and they were alienated from the other Japanese in the camps.

Despite their best efforts, most of them could not convince the Australian authorities of their loyalty and were not released. For example, Stan Suzuki, who appears in this book, is based on a real person who felt a strong sense of Australian pride and was ashamed of his Japanese ancestry, but because he had worked as a land surveyor before the war, the Australian authorities thought it dangerous to let him roam freely during the war; they were worried that he might become a spy for Japan and leak information about the Australian border. He was bullied in the camp and became so depressed that he attempted suicide. It was only after several years that he was finally released from the camp.

Other mixed race internees, and Japanese internees who had lived in Australia for a long time, were different and struggled with their loyalties to Japan and Australia. One woman I spoke to said that her father had become withdrawn and depressed while interned during the war. She thought it was because he felt conflicted as a Japanese who had lived in Australia for 50 years. Essentially, the camps were a "melting pot" of different cultures and loyalties, and so naturally conflicts arose.

--This relates to the previous question, but as people of the same Japanese descent, what are some social or historical differences between Japanese Australians and Japanese Americans? Do you think there are any particular characteristics of Japanese Australians among the other Japanese people?

CP: At the end of the war, most Japanese people in Australia were repatriated to Japan, whether they wanted to or not. Only those who were married to Australians or born in Australia were allowed to remain in Australia. Some people were forced to return to Japan even though they had been living in Australia for more than 50 years.

As a result, after the war, the number of Japanese living in Australia became very small, with only about 300 people registered as Japanese. They faced a lot of discrimination. For example, Broome was heavily attacked by the Japanese army during the war, so when Japanese who had lived in Broome before the war returned to the town, the people around them were unfriendly and it was difficult to find work. After the war, many Japanese Australians changed their Japanese surnames.

Additionally, for many years the Australian government had a racist immigration policy that only accepted white people, known as the "White Australia Policy." Although some Japanese "war brides" (women who married Australian soldiers stationed in Japan) were allowed to immigrate to Australia in the 1950s, it was not until 1972 that the discriminatory policy was completely abolished.

Therefore, there are not many people who call themselves 4th or 5th generation Japanese Australians (although there are). Some may not even be aware that they are Japanese. In Australia, most Japanese people, like me, are 1st or 2nd generation. I think this is a big difference between Japanese Australians and Japanese Americans. In Australia, we can be said to be relatively recent immigrants (those who came after the war).

When I was a field researcher for the Nippon Foundation's Global Young Japanese Study, I met many fourth and fifth generation Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians who were very proud of their Japanese traditions (cooking Japanese food and celebrating Japanese festivals), but could not speak or understand Japanese.

This was quite surprising to me, because in Australia, Japanese people who understand Japanese tend to feel a strong connection to their Japanese heritage, and many go to Japanese language schools on Saturdays (I didn't) and find community there.

Prefectural associations organize and develop

INTERVIEWER Do you think Japanese people or Japanese-Canadians living in Australia understand the history that began with Japanese people migrating to Australia in the Meiji era? If not, why do you think that is?

CP: There is limited knowledge about what migration from Japan to Australia was like. I think that's because it's not taught in schools. Maybe some Japanese people learn it from their parents or in Saturday school. I studied Japanese at university, so I learned a bit of history there, but I learned much more when I researched it for After Darkness.

--Are Japanese and Japanese-Americans in Australia organized? Are there any organizations like the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) in the US? If so, what kind of activities do they carry out?

CP: Japanese people living in Australia are not organized like Japanese people in the United States. I think that's because the Japanese population in Australia is small (about 71,000 people: see 2016statistic) and most of them are recent immigrants. There is no formal national organization like in North America. However, prefectural associations have been organized recently. As far as I know, there are Okinawa Kenjinkai in Sydney and Melbourne, Kanagawa Kenjinkai in Sydney, Chiba Kenjinkai in Sydney, Fukuoka Kenjinkai in Sydney, Fukushima Kenjinkai in Perth, and Wakayama Kenjinkai on Thursday Island.

In this way, Japanese people in Australia are beginning to organize themselves and build communities. I am also an active member of a group called Nikkei Australia, a private group dedicated to preserving and promoting the heritage of the Japanese diaspora in Australia. We have members in Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Perth and Broome, and are involved in a variety of projects, from history to art to academic research. We also hold regular social events around Australia.

-- In general, there doesn't seem to be much interaction between Japanese people living abroad for work or other reasons and people of Japanese descent who have roots in both that country and Japan (for example, Japanese-Americans), but what about in Australia? Is there interaction between Japanese-Australians and Japanese people living in Australia?

CP: There isn't much interaction between Japanese people who are temporarily residing or working in Australia and Japanese people with Australian roots. When I was at university, I belonged to the Japanese Society and got to know Japanese students studying abroad. In Sydney, where I live, there is a Japanese film festival and a "Matsuri Japan Festival" held every year, but other than that, I haven't had many opportunities to meet Japanese people who have recently come to Australia.

Organisations like the Nippon Foundation and Japanese Australians could do more to build bridges between the two groups.

Continued >>

© 2023 Ryusuke Kawai