* Continuation of part 1 , the following story is told by the author's grandfather, Rokuro Tojo, from a first-person narration.....

A NEW STAGE

In the two years that my contract lasted at the Santa Bárbara hacienda, I learned the language and, above all, the customs of the people. I could return to Japan, however, my motivations were no longer economic; I felt the need to continue providing my knowledge to my fellow citizens in their own language, and to low-income families who, because they lived far from the capital, had medical services that were scarce and inefficient, so I decided to stay a little longer.

Establishing myself in the town of San Luis de Cañete was the most advisable option to continue my work, due to its proximity to the farms where I already had my patients. However, being a large city, I could not practice my profession freely, since I lacked certification from the Peruvian government.

For this reason, they suggested that I move further into the province, to the town of Lunahuaná, where many compatriots had become independent, renting land for the cultivation of bread products and fruits, or dedicating themselves to commerce in general.

With the support of some friends, I managed to move without any setbacks and settle in the Socsi neighborhood, where I restarted caring for pregnant Japanese women in the town and its surroundings.

In many cases I had to care for families with few economic resources who could not pay for consultations or medications with money. In exchange for this, they paid me with animals such as chickens, ducks and pigs, or fruits from the region such as soursop, medlar, cherimoya and grapes.

As the years went by, the Japanese population was increasing, because the area was very prosperous and business owners called their relatives to help them in their establishments or with agricultural work, so they could later become independent. One of those families were the Iwamotos: the father, called Takematsu, Kino, the mother, and his 12-year-old daughter Matsue, with whom years later he would form a family.

In addition to being neighbors, with the Iwamotos we also integrated a “ tanomoshi ” (system of collective funds that helped the Japanese prosper in Peru). With the money raised they became independent, opening a grocery and hardware store, where they did very well.

During a visit, Mr. Iwamoto proposed to me to marry his daughter Matsue (an arranged marriage, Japanese style), who was already 15 years old. From this happy union we had four daughters: Keiko, Shigueko, Teruko and Katsuko.

On many occasions they came looking for me urgently from other towns, having to travel at night. One day, I was intercepted by some highway robbers, armed with shotguns. At that moment I thought the worst: would they steal my medical instruments? My money? My horse?

It happened that the wife of one of them was my patient and, after recognizing me, she wished me good night and ordered to let me pass to continue on my way. I didn't know he was so famous, but from that day on, I traveled more calmly along the winding roads of the interior of Lunahuaná.

When I was gone for several days, I left the care in the office to Matsue, who helped me with simple cures until my return. We sent the eldest of my daughters, Keiko, to San Vicente de Cañete, with a friendly family, to learn sewing, and Shigueko, when she was six years old, helped us with the housework and care in the office.

It was during this time that we decided to move to the center of the city, to a much larger house that had a small garden with fruit trees and many flowers. It was the culmination of many years of effort.

Anti-Japanese Campaign

As the city grew, the patients also increased, arousing the envy and jealousy of two Peruvian doctors who treated in Lunahuaná. This rivalry became evident when he reported me to the city commissioner for not being authorized to practice the profession of doctor. I received a verbal warning from the police authority and my office was closed. Aware of my situation and respecting the law, I stopped seeing patients and only dispensed simple prescriptions at the pharmacy, maintaining a low profile.

By 1931, an anti-Japanese campaign was developing in political spheres, condemning the military expansion of the Empire in Asia. This also found justification in sectors of the citizenry who saw the rapid progress of the Japanese in different production and business activities. They said that we were taking jobs away from other Peruvians.

Parallel to these events and, joining the popular fervor, in Lunahuaná the doctors proceeded to sue me judicially in the city of Lima for “illegal practice of medicine and promoting abortion.” As a result of this complaint, the Judiciary imposed a penalty for “illegal practice of the medical profession,” sentencing me to two years in prison.

I was provisionally detained in the city police station until the order for my transfer to the city of Lima arrived. Some neighbors and friends, aware of my situation, interceded with the police authority, arguing for exemplary conduct and altruistic attitude towards those most in need, requesting provisional release; however, it was not accepted.

While waiting for the transfer, imprisoned in Lunahuaná, Shigueko, now seven years old, brought me food every day, and we talked about how good she should behave and take care of her little sisters Teruko, three years old, and Katsuko, one year old, while I I was absent She didn't understand why and just cried.

The hatred of everything Japanese had also permeated the prison population, so the treatment I received was very unpleasant, with discrimination and constant abuse.

The end

Year 1934. After being released, I returned to Lunahuaná, alongside my family and friends. But everything was different, starting with me. I was no longer the same! He spent his days in deep depression, with no desire to do anything. He lived fatigued, irritable and sad. He slept little. I sat in a rocking chair every day looking at the garden, but my mind was blank.

After a few months, and despite Matsue's attention, my condition did not improve, so my family and friends, in order for me to forget the bad times experienced in prison, believed that it was better for me to return to Japan for a while. to recover.

And so it was that, in May 1935, after 25 years, I was once again in the port of Callao to embark for my homeland, with the hope of reuniting with my family and friends. Putting an end, without knowing it yet, to a stage of my life that knew joys and sadness.

The letters stopped arriving

Unfortunately, after his return to Japan, my grandfather did not improve as expected. Through a relative of his, he sent some letters and photos of his stay in Fukushima. He said that little by little he was regaining his sanity and that he missed his family in Peru and that he would return soon.

However, he was never able to reunite with his family. The outbreak of World War II presented itself as a new obstacle. Any communication with Japan was prohibited and, therefore, it was impossible to think of a quick return. His letters no longer arrived. As time went by, communication with the family was lost and no more was known about his state of health, or if he had died.

In Peru, grandmother Matsue (whom in the family we called “Mamita”), had to take care of the family's well-being alone. And life continued.

Posthumous recognition

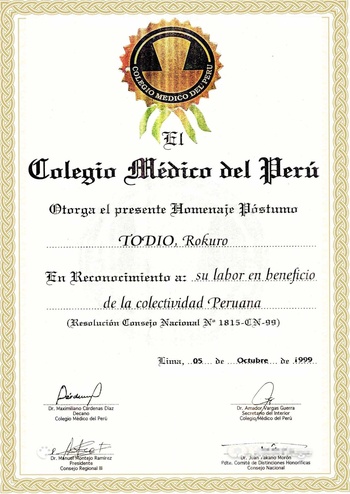

In October 1991, the Medical College of Peru paid posthumous tribute to five outstanding Japanese doctors who made their valuable contributions to Peruvian medicine. They were Rokuro Tojo (Todio), Yoshigoro Tsuchiya, Kosey Inami, Makoto Tsuneshige and Genji Niimura. The tribute was given within the framework of the 30 years of the Medical College, as well as the Centennial of Japanese Immigration to Peru.

© 2023 Takahashi Takashi