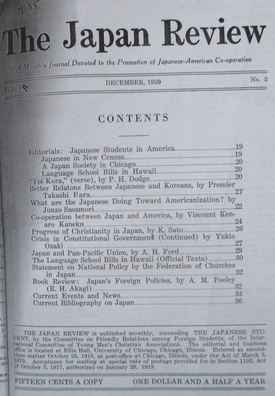

We already know that on his trip to Japan in 1917, Kato met with Vice Minister of Education Tadokoro, who told Kato that he hoped the Japanese language was being taught to the Nisei (American-born, second generation Japanese) by their immigrant parents and felt that Japanese language education should be controlled by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.1 Did Kato actually make contact with the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and was he asked to publish a new magazine with international relations between the countries as its message? Or did his personal experiences alone make him feel so keenly that Japan was misunderstood in America, warranting this change in his publishing interests? Since The Japan Review continued to be published by the Committee on Friendly Relations Among Foreign Students, justas it was before Kato’s Japan visit, it is difficult to conclude that its existence was result of a direct offer from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs.

Seeing that The Japan Review's credo was “Read about Japan, Think of Japan. Visit Japan… Talk with the Japanese,” it is clear that Kato intended to provide the public with unbiased, straight forward information on Japan.2 But was independence of this sort actually possible?

In February 1920, soon after The Japan Review began publication, Junpei Aneha, the Japanese consul in Chicago, corresponded with Kosai Uchida, Minister of Foreign Affairs in Tokyo, inquiring about payments to three Japanese students who contributed to The Japan Review. Aneha also reported that the magazine did not have enough subscriptions or advertisements to support student staff and pay them, as had originally been anticipated.3

The Japanese government’s direct involvement in this project may be a result of Kato’s previous connection with the Ministry of Education in Japan and in fact, Kato had contacted the Japanese Consulate in Chicago before he went back to Japan. In May 1917, Kato and the Japanese Consul, Saburo Kurusu, were invited as guest speakers to the eighth annual Journalism Week, sponsored by the University of Missouri, and to a big “Made-In-Japan” banquet that was held for 550 guests at the end of Journalism Week. In his speech, Consul Kurusu assured the audience of the enduring friendship between Japan and America, and in his speech, Kato applauded, “the Japanese in America,” claiming that the presence of Japanese students “serves to increase the feeling of brotherhood and cooperation which Japan holds for the United States.”4

All signs indicate that Kato had built a good relationship with the Japanese government, from the consulate in Chicago to the Foreign Ministry and Ministry of Education in Tokyo. Upon the request from the Chicago consul to help Kato, the Foreign Ministry immediately agreed to pay two hundred dollars total to the Japanese students.5 Those three students might have been Kennosuke Sato from University of Illinois, Shiko Kusama from University of Chicago and Shigeyoshi Obata from University of Wisconsin, each of whom had contributed several articles to The Japan Review.

Consul Aneha also planned to distribute The Japan Review (which was published in English) to libraries throughout the U.S. and Canada. Kato suggested that Aneha distribute them to schools and churches instead, since guest speakers visiting elementary and middle schools and churches often commented on the Japanese situation.6 A one-year trial of The Japan Review was finalized7 and about $2,765 was budgeted to distribute the magazine free for a year to 2,500 libraries in total (2,236 in the US and 250 in Canada.)8 Eventually, Kato reported to the consulate that he had to give up distribution in Canada as printing costs had risen, and that he could only afford to distribute 2100 copies to libraries in the U.S.9

The financial support from the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs was equivalent to more than $100,000 in today’s dollars, an enormous amount of support for a magazine published by students. Furthermore, the Japanese government’s involvement in the magazine was treated as top secret, and correspondence between the Ministry in Tokyo and the consulate in Chicago was conducted via secret telegrams and ciphers.10

The Chicago YMCA also supported Kato by holding an open forum on January 13, 1921, on “the Japanese question,” since it was “probably one of the most important topics of the day.”11 However, in summer 1921, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Tokyo decided to stop supporting The Japan Review upon the recommendation from Consul Kuwashima in Chicago.12 The huge cost of distribution obviously had not brought about the effect that the Japanese government had expected.

Despite this loss of funding, The Japan Review continued until April 1922, and Kato explained the reason for its termination as follows:

“We have done our best to continue it, but the principal supporters who have been making the publication possible by their generous donations have ceased to manifest their interest, and consequently, we have been forced into a small debt, and we see no way out, except to stop all expenses. …our publication is a specialized and narrow one, and we never have enjoyed wide circulation, and perhaps, the magazine of this kind has no right to exist.”13

The principal supporter, of course, had been the Japanese government. This author still wonders if The Japan Review was really the type of magazine Kato wished to publish.

Katuji Kato as medical doctor and associate professor at University of Chicago

Throughout the period when he was involved in publishing The Japan Review, Kato had been living in California and since around 1921, had been working as a physician in an internal medicine practice. He had a big family, with four children born in Illinois and another four children born in California in 1921, 1925, 1926, and 1929.14 Kato received his Doctor of Medicine degree in 1922 and by 1924, had licenses to practice medicine in both Illinois and California. Kato “practiced medicine in Los Angeles before joining the University of Chicago as faculty member in 1929.”15

He also contributed a long article on the physical growth of Japanese children to the Rafu Shimpo, a Japanese vernacular newspaper published out of Los Angeles, in summer 1926.16 Unfortunately, on June 30, 1930, his wife, Koma, died in Los Angeles, when she was only 40 years old. Kato went back to Japan with his eight children in August17 and returned to Chicago in December 1930 with his first son, sixteen year old Eimei, and his brother-in-law, Shinichi Noguchi.18 We presume that he left the other seven small children behind in his family’s hands in Japan. Noguchi was Koma’s brother. He had previously come to the U.S. in 1917, and lived at 205 East Ontario Street in Chicago while working as a domestic servant.19

Kato returned to Chicago and became an instructor in the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Chicago beginning September 1, 1930.20 The Department of Pediatrics had just opened in the Bobs Roberts Memorial Hospital that same year, and Kato was one of the first staff accepted into the department as a hematologist; he was also the first to perform children's bone marrow studies in the U.S.21 He was promoted in July 1935 to the rank of assistant professor of pediatrics at the University of Chicago.22 His discovery of the way that cobalt reacts on the iron in bone marrow was nationally reported.23

He remarried, this time to Dorothy Stabler, a Wisconsin native and laboratory technician at the University of Chicago, in June 1935 and took her back to Japan in 1938.24 By the time Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, he had built a brilliant career as a hematologist at Billings Hospital in Chicago25 26.

Once the war against Japan began, Kato left Chicago alone aboard the Gripsholm, the first exchange ship back to Japan from New York,in June 1942, leaving his wife behind. Shunsuke Tsurumi, son of famous politician Yusuke Tsurumi and a noted critic, was also on the Gripsholm andcommented about Kato some years later in wonder: “I do not understand why Katsuji Kato chose to return to Japan. His excellence was well accepted in America, regardless of race.”27 Ultimately, no-one really understands why Kato left his wife and America.

Eight years later, in November 1950, Kato returned to the U.S. post-war, as vice president of Tokyo Medical College and Director of the College Hospital. He was on a tour hosted by the American Red Cross Blood Centers, to gather “information for the setting up of a blood program for the Japanese Red Cross” and “to study problems related to establishment of a blood bank in Tokyo.”28 When he stopped by Kalamazoo College, Kato was delighted with the many changes to the college, and also recalled the “good old days” when he had to carry water from the basement and coal for the little stove used to heat his room.29

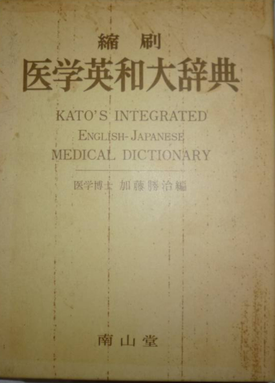

One year before his death in 1960, Kato published the Integrated English Japanese Medical Dictionary, which has been reprinted twelve times in several editions. It is still in print, even to the present day.

Kafu Nagai, who had cynically laughed at the pious Christian in his short story, died in 1959 with his petty jealousy toward Kato cast in stone, petrified in his warped story. If this was some sort of contest, Katsuji Kato was the winner. His death on September 4, 1961 at the age of 75 was widely reported in the U.S., even though it had been almost twenty years since he had returned to Japan.

Notes:

1. Shin Sekai, January 5, 1918.

2. The Japan Review, October 1920.

3. Aneha’s letter to Uchida dated February 11, 1920, Diplomatic Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 1-3-1-1_49-001.

4. The Evening Missourian, May 20, 1917.

5. Hokubei Mainichi, September 4, 1997, Report May 7, 1920, Diplomatic Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 1-3-1-1_49-001.

6. Consul Report Diplomatic Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 1-3-1-1_49-001, No date.

7. Kuwashima Consul Report, November 1920, Diplomatic Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 1-3-1-1_49-001.

8. Consul Report, Diplomatic Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 1-3-1-1_49-001, No date.

9. Kuwashima Consul Report December 13 1920, Diplomatic Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 1-3-1-1_49-001.

10. Hokubei Mainichi, September 4, 1997.

11. Daily Maroon, January 11, 1921.

12. Kuwashima Consul Report dated June 20, 1921, Diplomatic Archives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan 1-3-1-1_49-001.

13. Kato’s letter to Griffis dated September 20, 1922, The William Elliot Griffis Collection, Rutgers University, Reel 32.

14. 1930 census.

15. University of Chicago Magazine, November 1961.

16. Rafu Shimpo, August 15, 1926.

17. Rafu Shimpo, August 24, 1930.

18. Washington Passenger and List 1882-1965.

19. 1930 census.

20. University Record, October 1930.

21. Medicine on Midway, January 1978.

22. University of Chicago Magazine, November 1935.

23. The Bristol Herald Courier, November 19, 1936.

24. Washington, Passenger and Crew Lists 1882-1965.

25. Daily Maroon, February 5, 1941.

26. University of Chicago Magazine, November 1961.

27. Tsurumi, Shunsuke, Nichibei Kokansen, page 246.

28. Medicine on the Midway, April 1950

29. Kalamazoo College Alumnus, February 1950.

© 2022 Takako Day