Imagine the president signs an order incarcerating not just you, but your entire family: your kids, parents, aunts, uncles, and everyone related to you. Bank accounts are frozen, curfews are enforced, and your home is subject to searches without due process, reason, or warrant. You’re ordered to move to a military installation where your fate is unknown.

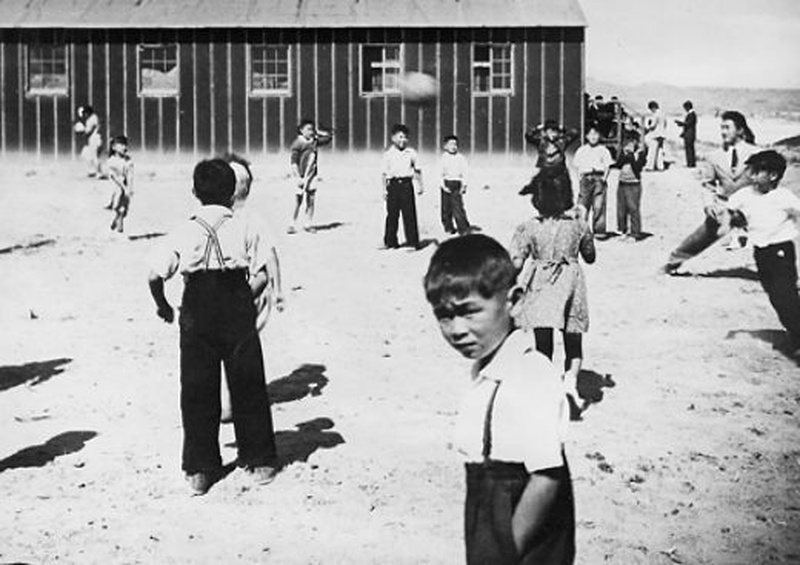

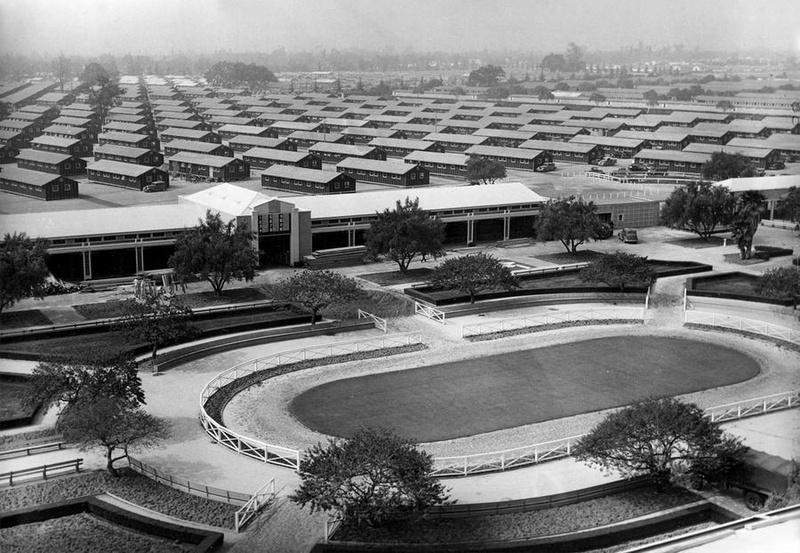

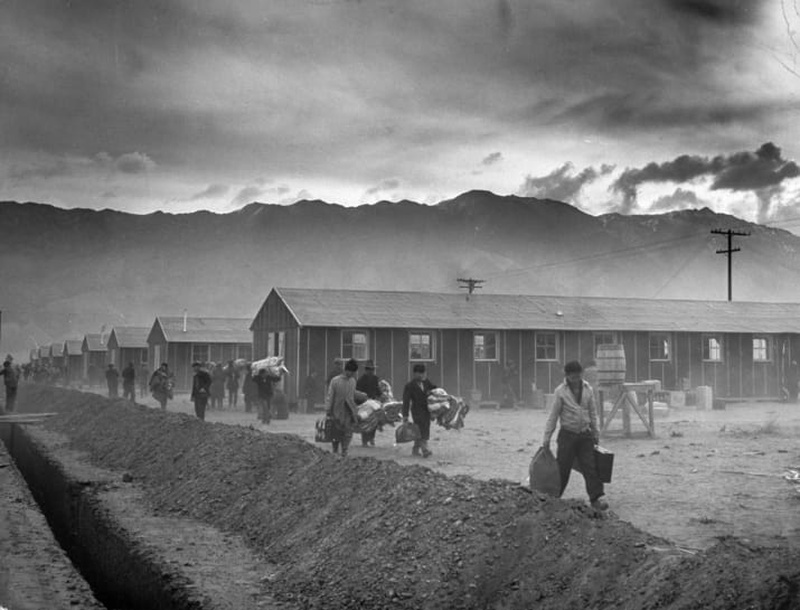

This isn’t hypothetical. It happened. My wife’s father and her grandparents were forced to give up their farm, their home, and most of their personal possessions to go live in a horse stall at a race track in San Bruno, California. By the end of WWII more than 120,000 men, women and children were incarcerated, most of them American citizens. Their crime? Simply, they were Japanese Americans.

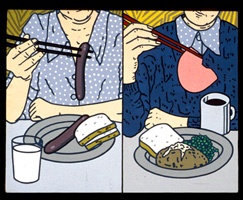

There are few things that can top America’s list of greatest and darkest undertakings, and jailing an ethnicity in its entirety, is one of them. Driven by the attack on Pearl Harbor and xenophobia stretching back to the 1800s, the American public turned a blind eye to Executive Order 9066. Mass ethnic incarceration was made possible by contractors like Del Webb and Griffith & Company who specialized in gut rehabs of horse stables and barrack construction for single family garrisons. At the same time food companies producing hot dogs, gelatinous meats, and other canned goods were ramping up to fill the War Department’s order, stockpiling all things non-Japanese for the 25 plus Japanese detention centers stretching from Arkansas to Washington.

Louise Kashino in 2007 on NPR Kitchen Sisters recalls:

“Oh, for awhile it was pretty bad. I remember once they gave us Vienna Sausage, the kind in the cans. They gave it to us for several days in a row. So people got diarrhea, and I remember one night everyone was rushing to the bathroom and sometimes you have to go two or three blocks to get to the bathroom. I remember the guards on top of fence stand turn their flood lights on and pointed their guns down at us. And it wasn’t a stampede. But it was just that everybody had a problem. And most of us purchased chamber pots, so we wouldn’t have to go out at night.”

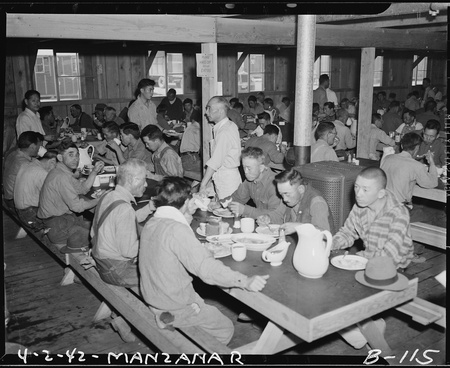

Some internment camps held up to 10,000 men, women, and children, yet America’s military today still face logistical challenges when feeding a single brigade of 1,500 soldiers. Imagine what a meal was like for a parent, child, or an elderly person in the harshest of camps like Tule Lake or Gila River:

“You lined up for your food, and then sat down at these long tables and ate there. Everybody squeezed in where they could. Just broke apart the family, because the kids were running around there was no family dinner.” (Howard Ikemoto, 2007, NPR Kitchen Sisters)

Richard Terasaki was seven when his family was sent to Gila River in the desert. He remembers chow time:

“Meals were prepared and served in mess halls for blocks of about 50 families. I can remember a monotonous repetition; for breakfast oatmeal and toast with ‘apple butter’ and beans, wieners and sauerkraut for lunch. I don’t remember having any thing really good like my mother used to cook. I especially missed ice cream especially since we owned an ice cream store before the incarceration. Families having meals together disappeared.” (2017)

Richard’s mother was bothered by the fact that she could not cook for herself or her family. This was the case for a number of the prisoners. The act and ritual of cooking and providing for one’s family simply vanished. One could argue the internment was meant to strip away rights, identity, and even culture. Because it was against the rules to cook your own food, meals issued in the camps became necessity. Yet internees still managed to smuggle in rice, secretly hunt, and feed themselves. Meals became both survival, and resistance.

“They had dirt floors in the barracks. My great grandmother would dig a hole and ferment her own rice wine or saké and store it. Bury it in the dirt. That was a big secret, they didn’t allow it in the camps.” (Akemi Tamaribuchi, 2007, NPR Kitchen Sisters)

“Every block had saké makers – but it didn’t have any connection with the mess hall. They’d scrape off the rice at the bottom of the pan and make saké.” (Jimi Yamaichi, 2007, NPR Kitchen Sisters)

“Tule Lake is a fly way for Canadian Geese. So he dug this trench, and lay down put some gunny sack over himself and put feed in the trench. And sure enough the geese came down and their wings were trapped. My father threw the gunny sack onto the geese. Every barrack had this potbelly stove and he actually roasted it in there and we had our Christmas Goose.” (Howard Ikemoto, 2007, NPR Kitchen Sisters)

Perhaps the most blatant form of food related resistance was the incident at Mazanar. Thousands of prisoners convened and demanded the release of Harry Ueno, an internee cook who confronted camp officials about stealing provisions and selling them on the black market (Oliver, 2004, LA Times). Harry was detained by camp officials for allegedly attacking a member of the JACL (Japanese American Citizens League), and that evening troops opened fire on the crowd chanting for his release:

“‘I just can’t forget the night they shot the people. I just can’t forget,’ Ueno said in 1991, when as an octogenarian he made a pilgrimage to Manzanar. ‘I have to pray for their well-being. I have to tell people so it won’t happen again.’” (Oliver, 2004, LA Times)

Two people were killed and nine others injured. Harry was removed from the camp and spent a year in isolation. On his way to jail, the police threatened that he would never return and that no one, including his family, would ever know his whereabouts. Even under threat, he responded:

“Maybe you’re going to take me to some jail or someplace but someday you’re going to get punished the way you treat the Japanese people in the camp.” (Ueno, 1994, Densho Encyclopedia)

Harry passed away in 2004 and his story of resistance still lives on in Manzanar Martyr: An Interview With Harry Y Ueno.

Japanese Americans continue to reflect and educate the public about their personal, family, and historical experiences. Resistance, both conscious and subconscious, is synonymous with survival and woven deeply into our DNA. If the internment was intended to strip away culture and destroy families, we can say without pause the War Department failed. To the right is an image of my wife’s aunt preparing Ozoni (rice cake soup) for 元日 New Years Day celebration in Lombard, Illinois. She learned the recipe from her mother, Sawako Rose Tani, detained at Tanforan Racetrack and interned at Topaz (1942 – 1944).

*This article was originally published on the author's blog, Dose of Freedom on January 25, 2018.

© 2018 Freedom Nguyen