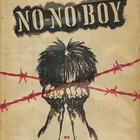

The first chapter of "No-No Boy," which consists of eleven chapters, begins with the protagonist Ichiro Yamada returning to his hometown of Seattle after being released from prison after the war. He refused to be drafted and served two years in prison, and he reunites with his family while carrying the weight of those two years on his shoulders. In the process, the author first brings to light the essence of the protagonist's problems.

Even though he did it of his own free will, why did he refuse conscription? For whom? Who was to blame? What exactly was he trying to do, or did he want to do? Who exactly is he? Ichiro has many questions for himself.

Conflict with Mother

Ichiro, who just turned 25, arrives in Seattle by bus. It's his first visit home in four years, having spent two years in a detention center and two years in prison.

He soon encounters Eto, a fellow Japanese, in town. Eto, who was in the military, realizes that Ichiro is a "No- No Boy, " a man who has refused to pledge allegiance to his country.

Eto spat on Ichiro, but Ichiro accepted it. The abuse relieved Ichiro's tension. As he walked through the town, a black man abused him, telling him to go back to Tokyo.

When Ichiro returns to the grocery store run by his parents, he is greeted by his kind but timid father. His father is an alcoholic and soothes his weak heart with alcohol. He barely speaks English. When asked why he came to America, his father says, "It was for money." He tells Ichiro that everyone is the same, and that they planned to return to Japan once they had made a lot of money.

On the other hand, my mother is strong-willed, meticulous, and stubbornly strong-willed. She is a fanatical "Japan believer" and still refuses to believe that Japan lost the war. However, she receives a letter from a fellow Brazilian of Japanese descent who also has no doubt that Japan will win, and believes that a ship returning to Japan will come to pick her up.

He is proud of his son for refusing to be drafted. He hopes to send his son to Japan someday. Ichiro, who respected his mother's wishes and made the difficult decision to refuse conscription, murmurs about his feelings for his mother.

"My mother tortured me with her wicked, invisible hatred. She made my mouth open and my lips move. For that I spent two years in prison. An emptiness more terrifying and empty than the caves of hell. My mother was wicked and hated me and killed me. I will never know the meaning of happiness again, so at least I want my mother to be happy."

Blame yourself, blame the world

Ichiro worries and agonizes over how Japan and America exist within him.

"I wish with all my heart that I was Japanese, or American, but I am neither. I blame you, I blame myself, and I blame the world, a world of nations fighting, killing, hating, destroying each other, and yet it is not enough, so they kill, hate, and destroy again and again."

Ichiro has a younger brother named Taro. Taro is ashamed of his brother being a No-No Boy, and takes a defiant attitude towards his brother, trying to join the military without waiting to graduate from high school, despite their parents' objections. This is to prove that he is an American. Ichiro is worried, but there is nothing he can do.

Comrades who died in battle

Although Ichiro feels resentment towards his mother, he is taken by her to visit the homes of Japanese acquaintances to say hello when he returns home. His mother brags that Ichiro, who was serving time in prison, did a great thing for Japan. However, the acquaintance tells him that her son died in battle as a soldier in the U.S. Army. Ichiro feels ashamed. And he feels intense anger towards his mother, who doesn't seem to feel anything for him.

Like Ichiro, there were Japanese Americans who refused to serve in the military. Some said they didn't need to serve if they weren't recognized as Americans, and others said they couldn't fight because their brothers were in the Japanese military. In contrast, many more Japanese Americans served in the military. And some died. Naturally, there were Japanese (Japanese American) families who were heartbroken.

Why didn't Ichiro fight?

"I didn't go to fight because I was weak and didn't know what to do. It wasn't my mother that I never understood. It was me."

Ichiro's father knows that his wife is mentally ill, but there is nothing he can do about it because she is sick. Even when her relatives send him letters from Japan pleading for them to send supplies, he feels sorry for his wife but is unable to do anything.

Drowning his troubles in alcohol, his father tearfully apologizes to Ichiro.

"I'm so sorry you had to go to prison because of us."

"That's fine, forget it," Ichiro replies.

Thus ends Ichiro's day back home for the first time in four years. He, his family, and his community have all changed because of the war. How should he live from now on? Ichiro begins to walk, trying to find the answer to the problem he is facing.

(Translation by the author)

Notes:

1. The original meaning of the term "No-No Boy" was someone who answered "no" to two questions asked by the government in the internment camps, pledging loyalty to the country, but author John Okada also refers to draft resisters as "No-No Boys" in his novel.

© 2016 Ryusuke Kawai