When they returned to their town, Maida, the Italians who had migrated to the United States were received as emissaries of a new, different, modern world, full of opportunities, living proof that there was a future outside, another life, other airs. They were the bold ones who had chosen to prosper abroad or be shipwrecked in the attempt, instead of languishing in their homeland.

The money they sent to their families boosted the local economy. Families that had relatives in America lived better than others. The wives of immigrants were called “white widows.”

I discovered all this by reading The Sons , a work in which Gay Talese tells the story of his ancestors, especially that of his father Joseph, an Italian tailor who migrated to the United States in the early 1920s.

“Very few of these women, who had been deprived of their husbands for a long time, seemed to suffer from grief or depression. And although they may sporadically feel more widow-like in private, in public they radiated joy and security,” says Talese, referring to “white widows.”

I wonder if in Japan the wives of immigrants in Peru were like white widows. Did their families live better than the rest thanks to remittances? Were immigrants seen as adventurers who had dared to cross the ocean to forge a different destiny? Were they admired? Perhaps envied?

While reading Talese's monumental work, full of extraordinary stories of ordinary people, I thought about the extraordinary stories of Japanese immigrants in Peru that we do not know. Of the thousands of Japanese who arrived in Peru, how many carried diaries? Where are they? How many great stories would there be in them?

When I think about the women who upon arriving in Peru discovered that the men who were waiting for them at the port and with whom they would have to spend the rest of their lives (because that was how marriage was in those times, you were married forever even if it was just a arranged), they did not resemble those dapper and handsome men who appeared in the photos that had been sent to them and to whom they were married, I imagine their disappointment, their sadness and, finally, their resignation.

I presume that some of them poured out their feelings in a diary, writing in it what they dared not tell anyone out of modesty. And despite the frustration or sadness they felt at the beginning, in the end they managed to settle in Peru, start a family and perhaps be happy. So many stories! No?

I think about the history of Japanese immigration to Peru and I prefer not to think about dates or generalizations that turn individuals into an indistinguishable part of a mass (the Japanese worked hard, bequeathed values to their children, etc.), but rather into unique and unrepeatable, with their own voice, face and feelings.

Joseph Talese is married to an Italian-American woman, has two children born in the United States, and runs a tailor shop that allows the family to live a comfortable life. He is not rich, but he is a successful immigrant and a model citizen in the small town where he lives, until the Second World War breaks out and his heart breaks in two: a piece goes to Italy, his homeland and that of his ancestors, the land where his mother and brothers live, and the other belongs to the United States, the homeland of his wife and children, the promised land in which he dreamed of living since he was a child, his dream fulfilled.

I was reading his story and thinking about how much I would like to read a similar story about a Japanese immigrant in Peru. The Japanese suffered much more than Joseph Talese (nothing was taken from him or deported) during the war, but we do not have individual stories, only figures, dates or data that encompass everyone, without particularizing them, as if all the dramas were the same. , as if each person were not a world that deserves its own story. I'm not saying that data is unimportant, not at all, but I prefer emotions.

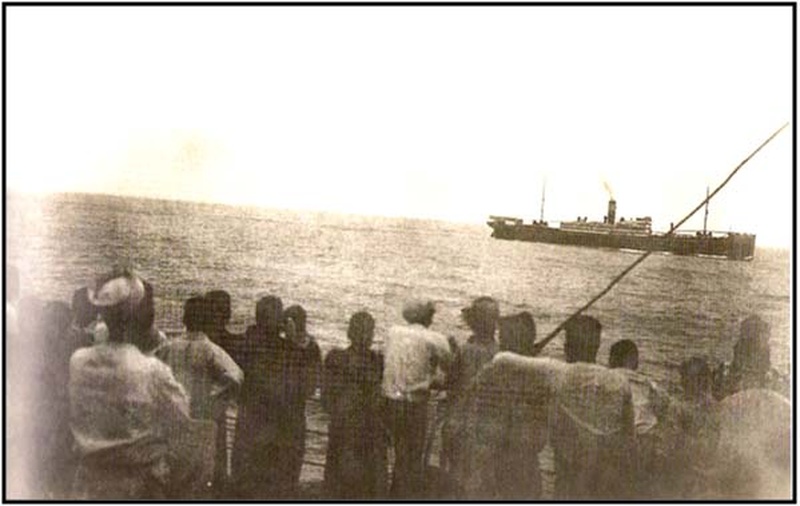

I think of the old man who migrated to Peru when he was 15 years old and who almost eighty years later clearly remembered his departure from Japan. He boarded the boat with his father, but when the gong rang, warning the people who had boarded to say goodbye that he had to leave, the then teenager realized that his father had left: “I'm sure he didn't want to say goodbye because of the sadness he felt. He had to send his 15-year-old son (to Peru). I called 'tochan, tochan', but he was gone. “That was the farewell.”

Almost all the information I have read about the trips of Japanese immigrants to Peru (when they arrived, what was the name of the ship, how many passengers it carried, what prefecture they were from, etc.) has been erased from my memory. However, I always remember the farewell of that 15-year-old boy. I imagine the heavy rain (because it rained that day), the sound of the gong, the confusion of the teenager when he finds himself alone, the grief of the father who sneaks away to avoid a painful goodbye, the ship that leaves the port of Yokohama, the father on land that contemplates how the horizon swallows the ship that takes its son forever, the son who begins a new life.

© Enrique Higa