For Japanese Americans observing the election, the use of race-baiting elicited anger and, at times, a darkly comedic response. As Natasha Varner of Densho explains in her 2016 article about absentee voting in camp, Japanese American inmates still faced several bureaucratic hurdles from election boards two years after the 1942 election that made voting from camp difficult if not impossible. Larry Tajiri of the Pacific Citizen offered regular, insightful commentary to readers. Tajiri predicted that voters would still be split between Democrats and Republicans, but predicted that the majority of Japanese American voters would cast their ballots for Roosevelt because of the race-baiting tactics of Republicans.

Another development which will influence those Nisei who will vote on November 7 is the fact that California Republicans are using the absent evacuees as political whipping-boys and have charged that the impending return of Japanese Americans to their homes is a New Deal plot. Republican Congressional nominees Carter, Anderson, Gearhart, Leroy Johnson, Rolph, Hinshaw, and Poulson have engaged in race-bating during the campaign and have announced their opposition to the return of the civil rights of Japanese Americans.

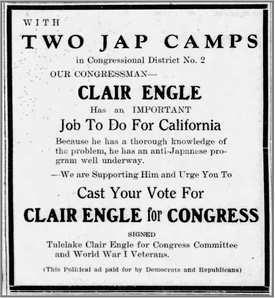

The exception among the Democrats was Clair Engle, who Tajiri described as “violent as any member of California’s racist bloc of Congress.” Clair Engle, whose district coincidentally included Manzanar and Tule Lake, used his anti-Japanese activities to his advantage.

Following the Tule Lake riot in November 1943, Engle went to Tule Lake concentration camp as part of investigative group and proposed legislation to deport the Tule Lake inmates. Voters in the district printed ads in favor of Engle, whom they declared an anti-New Deal Democrat who authored legislation to “handle these Japs now and after the war.”

It should be noted that none of the Tule Lake inmates were permitted to vote, due to the restrictions placed on them in the segregation center. Tajiri pointed out the comedic irony that Engle’s opponent had attacked him for (inaccurately) trying to solicit votes from Tule Lake inmates.

Despite the failed campaigns to keep Japanese Americans from voting in 1942, several politicians continued to keep Japanese American ballots from being counted. In 1943, the Wyoming state legislature successfully passed a law to deny Japanese Americans at Heart Mountain camp—including soldiers who enlisted from the camp—from acquiring absentee ballots. For resettlers, residency laws barred many from participating in the election.

Still, Japanese Americans who maintained their West Coast registration could participate in the 1944 presidential election via absentee ballots. In May 1944, San Francisco Register of Voters Cameron King told the War Relocation Authority that former California residents in camp, including those turning 18 in 1944, are eligible to vote in the general election. In July 1944, the Heart Mountain Sentinel printed project attorney Bryon Ver Ploeg’s instructions to camp inmates to register with the clerks of their former counties on the West Coast. Ver Ploeg stated that if the voter did not vote in the previous presidential or primary election that their registration would be cancelled.

In September, former Seattle attorney Clarence Arai informed Minidoka Project Attorney Frank S. Barrett about his efforts to secure absentee ballots for inmates in camp. On September 15th, Seattle Comptroller W.C. Thomas wrote to Arai that former Seattle residents in camp would need to send a petition to his office to receive absentee ballots. Within a few days, Arai gathered signatures and submitted his petition for ballots to the Seattle Comptroller’s office on the 18th.

In the weeks leading up to Election Day 1944, Larry Tajiri devoted extensive space in his editorials to extoll readers the importance of voting. October 28, 1944, he told readers:

On the seventh of November the people will go to the polls in the most crucial election in the nation’s history. And among the electorate will be Japanese Americans, As in years past the Japanese American vote will be small, an insignificant minority in comparison to the 45,000,000 expected votes…But to every Nisei American who has to a lesser or a greater degree been deprived of his civil rights since the start of the war, the vote is more than ever a precious thing to be used with care and discretion.

In the last issue before the election, Tajiri offered another analysis of the effects of the incarceration on Nisei voting patterns. Here he made the compelling argument that the forced removal policy inadvertently disenfranchised many inmates due to: 1. The restrictions placed on absentee voting for inmates in 1942 (one needed to be registered by April 1942 to vote in the November elections), and 2. For resettlers, the official rulings that the amount of time they spent in their new home state did not meet the requirements for voter registration.

Unlike in 1942, where a sizeable number of Nisei voted by absentee ballots from assembly centers or concentration camps, Tajiri surmised that most Nisei had not been able to register for the 1944 election. Demoralized from years of imprisonment, the Nisei in camp had little interest in hometown politics. Tajiri concluded with a poignant description of the effects of camp on Nisei voters:

“The internecine warfare on the political refront seems unreal from a barrack window in a relocation camp. The mess halls, the gray barracks, the water tower and the silent desert on all sides have reality, but the world is far away.”

Outside the camps, voting measured the extent to which resettlers planned to stay in their new homes in the Midwest and East Coast. In Chicago, researcher Charles Kikuchi estimated that only a small percentage of Nisei resettlers in the city had the ability to vote.

An estimated 71% of the total resettler population is 21 years of age or over; 21% are Issei, or non-citizens ineligible to vote. This leaves about 53% meeting both age and citizenship requirements; slightly less than half this number, however, meet the one-year residence requirement. Of the estimated 1500 qualified resettlers, only a very small number are actually known to use as registrants. Those whom we know have registered are the type who say they intend to settle permanently in Chicago.

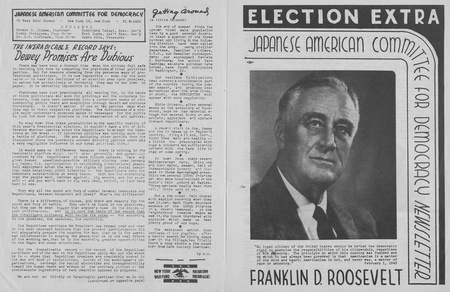

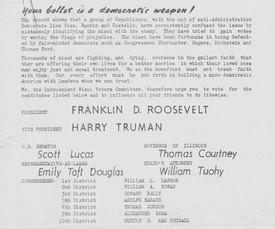

In resettlement cities such as Chicago and New York City, resettlers formed their own committees to mobilize voter turnout. The Independent Nisei Voting Committee of Chicago distributed a pamphlet instructing Nisei to vote with the Democratic party. In spite of Roosevelt’s signing of Executive Order 9066, Nisei intellectuals backed the Democratic Party for its solid record of support for Japanese Americans over Republicans.

The pamphlet praised Roosevelt for supporting the return of Japanese Americans to the West Coast and his record of allowing the Nisei to serve in the Army (despite the Army’s initial removal of Nisei soldiers in 1942). Conversely, the author pointed that the national Republican ticket, led by Thomas Dewey and John Bricker, agreed with Earl Warren and Frederick Houser, California Republicans who they faulted as being among the chief proponents of the ongoing exclusion of Japanese Americans from California.

First we want a speedy end to this war, the destruction of fascism the world over and a United Nations organization that will be able to create and maintain an equitable and enduring peace. The able and inspiring leadership of President Roosevelt must not be cast aside at such a crucial period for the inexperienced services of Thomas Dewey, an isolationist-supported "Me-Tooer" and misquoter.

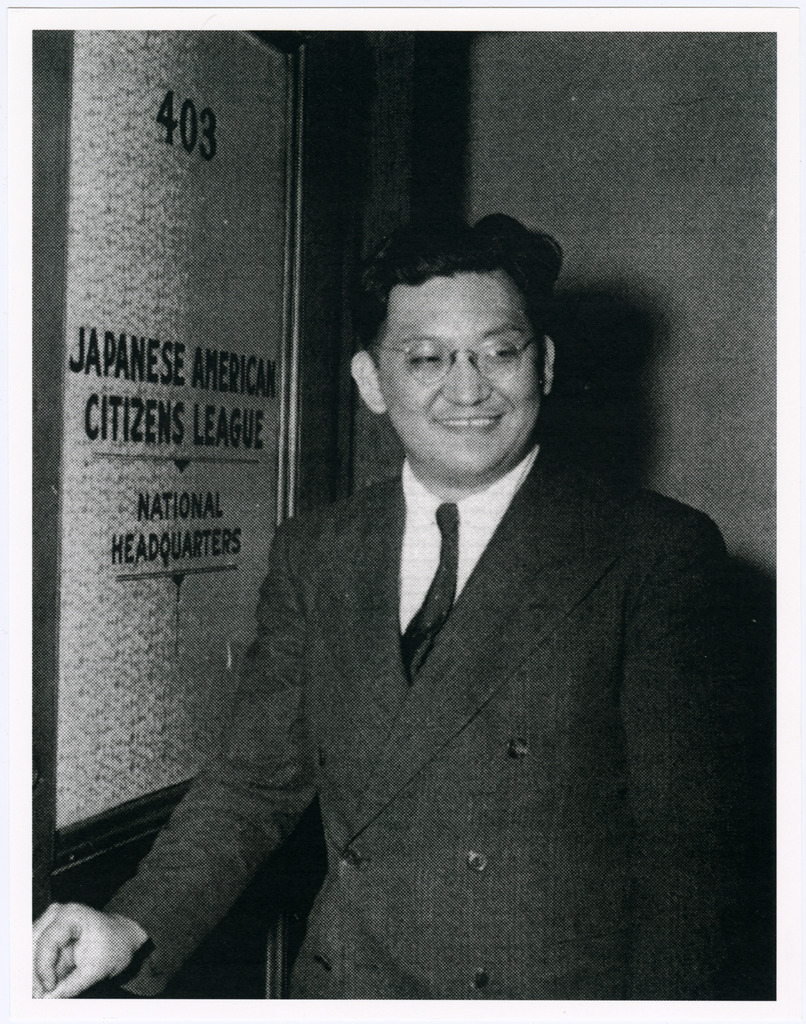

In New York City, the Japanese American Committee for Democracy worked with the left-wing National Negro Congress to organize a rally in support of Roosevelt in October 1944. Like the Independent Nisei Voting Committee and the Pacific Citizen (though the JACL was formally nonpartisan), the JACD backed Roosevelt as the sensible choice for Japanese Americans. In their Autumn 1944 newsletter, the JACD argued that Roosevelt, while the signer of Executive Order 9066, was not solely responsible for the incarceration. Rather, the committee blamed racists like General John Dewitt for pressuring Roosevelt to sign the order.

The JACD pointed to Roosevelt’s record of creating the WRA and supporting the creation of a Japanese American combat team as proof of his positive treatment of Japanese Americans. The Pacific Citizen, in turn, printed JACD member Dyke Miyagawa’s article on the group’s Rally for Roosevelt. The former editor of the Minidoka Irrigator, Miyagawa told PC readers about the event, which drew in 200 supporters. In his concluding remarks, Miyagawa gave an earnest analysis of the effects of the incarceration on political activism:

If the rally was any indication of the temper of Nisei throughout the country, then it can be set down as a symbol of the awareness which Japanese Americans have acquired since evacuation – the awareness that their future lies with the cause of all other citizens who work and fight for the men and ideals that are liberal and progressive in American politics.

Japanese American liberals welcomed the election of Roosevelt. In some ways, the election represented a turning point in the overt racism directed towards Japanese Americans by politicians. Larry Tajiri described John Costello’s loss as “the Twilight of the Demagogues.” Although anti-Japanese hatred did not disappear after the war, the subsidence of rumor-mongering and race-baiting involving Japanese Americans in electoral campaigns after 1945 is emblematic of a greater shift in perceptions.

Thanks in part to the positive depictions of Japanese American servicemembers, the false charges of espionage and sabotage levied against the community in 1942 slowly lost their traction. However, the anti-Japanese rhetoric, employed by West Coast politicians to criticize the liberal policies of the New Deal, foreshadowed the widespread red-baiting and opposition towards civil rights that unfolded in the next decade.

© 2024 Jonathan van Harmelen