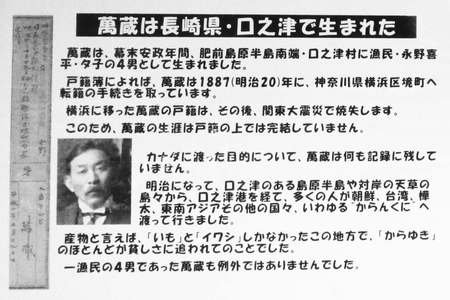

In Nagano’s hometown, Kuchinotsu (near Nagasaki), the local museum has a prominent display case devoted to “Nagano, First Japanese Immigrant to Canada.” However, the museum has no documents about any of Nagano’s early life abroad before the time he moved to Victoria in 1892. There is one document displayed behind glass that indicates Nagano must have been in Yokohama after 1887.1 It is an official form showing that Nagano transferred his permanent domicile to Yokohama in 1887.1 That was the same year his first son George was born in Kuchinotsu.

Yokohama became an “open port” after 1859, one of the few ports where foreigners were allowed to live and do business. By the 1880s the city was known as the “Gateway to the West.” At that time, Japan was undergoing a tremendous modernization. Its first movie house opened in 1870 and a rail line to Tokyo began operating in the same year.

Although there is no direct proof Nagano spent the years after 1888 in Yokohama, he did officially change his residence and he married a woman from Tokyo after the death of his first wife. Somehow he had to have acquired business skills in order to run a gift shop, and learned how to negotiate the exporting and importing of goods. He himself claimed he was in Yokohama in 1891. Circumstantial evidence places him in Yokohama several years earlier.

In summary, up until 1892, everything Nagano told Nakayama in 1920 should be disregarded, as no corroborated information can be found in Canada, Washington State or Japan. Only the events taking place after 1892 can be confirmed.

By 1920 Nagano was suffering from tuberculosis, and the next year fire destroyed most of his stock in his last gift shop at 1501 Government Street. Although Nagano left Victoria a sick man, with his business in ruins, during his first twenty years he had been the most successful Japanese businessman employing eleven people in three shops. He was a founding member of the Japanese Association and served as its first president in 1908. For a time he was quite prosperous. However, by 1921 he was operating only one rented store and living upstairs with his wife. Both sons had married and left Victoria.

When Nakayama dropped by for the interview, Nagano was in poor health still a proud man. Perhaps, rather than disappoint the learned journalist interviewing him, he elaborated the details of his life. Possibly the stories he told about his early years were tales he had heard told by other old-timers over sake in the late evenings. Within two years of the meeting with Nakayama, Nagano had returned to his hometown in Japan. He died on May 21, 1924. His remains are buried in the cemetery of the Gyokuho-ji Zen temple overlooking Kuchinotsu harbour.

While definitely not the first Japanese immigrant to British Columbia, he was a colourful and successful businessman. He raised a family whose descendants still live in North America. Today Nagano is remembered as a prominent early Japanese pioneer in Victoria.

As a final demonstration of the importance of Toyo Takata’s role in creating the myth of Manzo Nagano, two final examples are offered. The first is found in Roy Ito’s book, Stories of My People.

Ito mentions that Ken Mori met George Tatsuo Nagano, Nagano’s son in 1977, at a dinner marking the centennial of the first Japanese immigrant to reach Canada. Mori asked George if he had been aware that his father was the first Japanese immigrant to Canada. George explained that he only learned that fact from Toyo Takata when Toyo visited him in Los Angeles! He told Mori that he did not know much about his father’s early life, in fact, “his father was always too busy to talk to his two sons.”2

The second example comes from the author’s correspondence with George Nagano’s son Paul (Manzo’s grandson, born 1920) at the time a retired Baptist minister living in Alhambra, California. When contacted, Paul wrote back, “I’m sorry but, I am not able to uncover any background material of Manzo, especially his early experiences. Toyo Takata is the historian that has researched much about Manzo.”

In further correspondence, Rev. Paul indicated that Toyo Takata had provided him with most of the background information to write his own short biography of his grandfather. Paul’s account appeared in Gordon Nakayama’s book, Issei: Stories of Japanese Canadian Pioneers published in 1984. Rev. Paul’s account adds further contradictions to the story of his grandfather. One example is, he states that “Manzo was born on Nov. 26, 1853,” while most other accounts report he was born in 1855.

Someone once referred to Nagano as the Paul Bunyan of Japanese Canadians. But Paul Bunyan was a mythical Quebec logger (Bon Jean) before being transformed into a larger-than-life American hero who performed fantastic feats. Nagano was no mythical figure; he was a very real, important and respected member of the Japanese community of Victoria after his arrival in 1892.

When he told his story to Nakayama, for some reason, he spun a myth about his early life. A few of his claims were: that he arrived in New Westminster in 1877; fished for salmon for two years with an Italian partner; moved to Gastown in 1880 and worked loading lumber for a while; got restless and signed on a ship that travelled to Shanghai and then to Nagasaki; he said he was on another ship in 1884 going to Shanghai, Hong Kong; eventually he left that ship in New Westminster—not to stay, but moved to Whatcom County in Washington State to fish for halibut; one day a storm blew his boat up the Fraser River; returning to the United States he opened a tobacco shop in Seattle and later operated western-style restaurant in the city; he claimed to have returned to Japan in 1891 to open a western-style restaurant in Yokohama.

None of these claims, made in 1920 to Nakayama, can be corroborated in any other source. Only after his restaurant in Yokohama supposedly failed, prompting a move to Victoria in 1892 to open a store selling Japanese goods—does his true story begin. In the mythical story he told, about his wandering from 1877 to 1892, he never mentioned his first two wives or his son born in Japan, nor did he give any hint of how he learned to run a business.

If Nagano was not the first, who might it be?

Notes:

1. Kuchinotsu Museum of History and Folklore, Minamishimabara City, Nagasaki Prefecture.

2. Roy Ito, Stories of My People: A Japanese Canadian Journal, Nisei Veterans Association, Hamilton, Ontario, 1994.

*This article was originally published in the Nikkei Image, A publication of the Nikkei National Museum & Cultural Centre (Volume 28, No. 1).

© 2023 Ann-Lee Switzer, Gordon Switzer