In this column, I will round out my history of the amazing family of Aijiro and Nao Tashiro by discussing the lives of their younger sons Sabro (AKA Saburo or Sab) and Arthur.

Sabro Tashiro was born in New Haven, Connecticut in February 1910, and moved with his family to Seattle after the end of World War I. During the summer of 1925 and 1926, he worked at an American salmon cannery in Tenakee, Alaska, alongside Swedish, German, Greek, and Italian immigrants. In an article published shortly afterwards, he described his work:

“The company’s officials worked us pretty hard. We had a 10-hour day before the fishing season, getting cans and packing boxes ready to receive the salmon and when the season started we worked a full 17 hours—starting at 5 in the morning. My job was to throw the fish into a machine to be sliced ready for canning. I wore an oilskin, a rubber helmet and boots, but even a fireman’s outfit couldn’t have kept me from smelling fishy after handling 17,000 salmon a day….The scales made the floor slippery and I always was in danger of slipping and getting tangled up in the slicing machine.”

Tashiro added that the only food the company gave them was rice, salmon, and pork from pigs who were fed salmon—so that the rice was the only real expense for the company.

In fall 1927, after graduating from Broadway High School, Sabro enrolled at the University of Cincinnati, where his uncle Shiro was a professor and brother Aiji already enrolled. There Sabro attended the College of Liberal Arts and the College of Medicine.

In the 1930 census, he was listed as living in the house of Dr. Robert Kehoe, a doctor, as his house servant. During his undergraduate studies, Sabro was active with the University Y.M.C.A. In 1930, as chair of the YMCA Friendly Relations Committee, he presided at a banquet for foreign students and members of the University’s International Club of Cincinnati.

Sabro also engaged in literary pursuits during this time. In June 1933, Larry Tajiri wrote an article on the Tashiro family and mentioned, “Saburo Tashiro, medical student, who has contributed many a poem to Japanese English sections under the pen name ‘O’Brien.’” I have been unable thus far to locate any such pseudonymous poems, but one published in his own name, “Relativity,” was published in Shin Sekai in August 1932:

The Dipper swings across the

sky and spills

The stream of stars that flood

the Milky Way;

It swings—while death each

plaintive murmur stills,

It swings protesting centuries

away.Below, frail men desire

and dream and love,

With shining lies their petty

lives adorn,

Unmindful stalks the pallid

Moon above,

Patrolling starry skyways ‘till

morn.With morning comes that

brighter moon, the Sun.

Medallion on the tunic of the

sky;

It shines—while cities wither,

one by one

Will shine—when cities yet

unborn shall die.

After receiving his bachelor’s, Sabro enrolled in the Graduate School of Surgery at the University of Cincinnati. In July 1937, following his graduation from medical school, he was accepted as an intern at Cincinnati General Hospital. However, like his brother Aiji before him, in 1938 he suffered an attack of tuberculosis and was hospitalized for en extended period. With encouragement from the nurse who attended him, Sabro took up crocheting as a hobby.

After his bout with tuberculosis, he became interested in preventive aspects of the disease. While he ultimately recovered, the ravages of the disease, plus the need for his medical services, would prevent him from joining the U.S. Army during World War II.

In fall 1940, Sabro produced his draft card and mentioned his employer as Bethesda Hospital in Hamilton, Ohio. In 1941 he was named a resident at the School of surgery at Cincinnati General Hospital, where he specialized in brain surgery.

From 1942 to 1945, he was with the Office of Scientific Research and Development. During these same years, he studied for a bachelor of science in pathology, graduating in 1945. In the years that followed, he joined the staff of the Veterans Administration hospital at Togus, Maine, near Augusta.

In April 1953, Sabro transferred to the Veterans Administration hospital at Batavia, New York, where he worked as a surgeon and pathologist. He retired from medicine in 1958 and returned to live in Augusta, Maine.

In the years after, he concentrated on his crafts work, crocheting tablecloths and bedspreads, as well as creating ceramic figures. One of his creations, a crocheted tablecloth, took a major prize at a crafts fair in Genesee, New York, while another won a prize in Northampton, Massachusetts. He died on December 1, 1965.

Sabro’s younger brother Arthur Isoku Tashiro was born in Seattle on September 7, 1919—the youngest of the Tashiro siblings and the only one who did not spend his childhood in New England. He travelled alone with his mother Nao to Japan in 1923, then had to petition the American embassy for an emergency passport to return home the next year. After attending elementary school in Seattle, he moved with his parents to California in 1928.

The next year, Nao Tashiro died. Arthur was sent temporarily to Cincinnati, where two of his brothers had already settled, and he lived for a time at the house of his uncle Shiro Tashiro. During the 1930s, he transferred to the Voorhis Elementary School in San Dimas, California—Jerry Voorhis, the school’s founder and headmaster, would continue to follow his progress long afterwards. In May 1940 he published an article on Voorhis in Rafu Shimpo

In 1938, Arthur Tashiro moved to Boone, North Carolina with his brother Aiji and his wife, and over the following two years he pursued his studies at Appalachian State Teachers College (today’s Appalachian State University), majoring in English and history with the idea of becoming a teacher. During his time away from class, he traveled (mostly hitchhiking) across the country. According to a friend, “after spending 2 years in the South, he acquired a ‘Suthun’ accent and a deep tan.”

In summer 1940, Arthur published a three-part article in Kashu Mainichi, “I Traveled in the South,” on his experiences living and touring in the South. In it he spoke about such topics as Tennessee Mountaineers and moonshine, the beauties of Colonial Williamsburg, and regional slang such as “sho’ nuf” and “you all.”

Two pieces of Arthur’s commentary stand out. The first was about discovering, to his amazement, that many Southerners interpreted the Bible literally:

“During a visit to the home of one of my friends. I innocently became involved in an argument between father and son over the theory of evolution. The father clung to the old Biblical conception of creation, while the son, a freshman in college, upheld the Darwin theory of a gradual and transitional change. This is one of the many times in my life I wished I’d remained absolutely silent; I never dreamed an argument could get so heated. In the father’s viewpoint this was sacrilege.”

Even coming from a devout Christian family, Arthur was taken aback by the fundamentalism of the Bible Belt. More extensive and poignant was Arthur’s discussion of the racial climate he found in the South and the large-scale discrimination against African Americans which outraged him.

To the Southerner a Negro Is a “n———”. Even children are brought up to feel that they are definitely superior to the Negro. True, a Southerner may respect one or two individual members of the race whom he might know quite well and may treat them almost as an equal, but the colored race as a whole, he is reluctant to accept on an equal basis.

Two years ago I hitch-hiked up to New York with a Southern boy and when he saw colored people riding in the same subway car with white people he couldn’t understand it. As he expressed it, “Southern n———s aren’t so bad, but the n———rs they've got up here; they think they're too smart.”

Arthur meanwhile signed on as a freelancer for the Southern California Japanese American press. In July 1940, he published an account of an interview with his old teacher and mentor Jerry Voorhis, who had been elected to Congress and appointed to the Dies Committee (House Un-American Activities Committee). Voorhis forthrightly denied that Japanese Americans posed a threat to national security: “I have no doubt as to the unquestioned loyalty of the great majority of Japanese in this country.” Interestingly, Voorhis expressed ambivalence regarding HUAC. He told Tashiro that he did not agree with some of the methods that his colleagues on the committee had used in the past, but that its main function was to protect democracy.

Arthur seems to have remained in California for some time. When he filled out his draft card in October 1940, he listed himself as living with his brother Ken in Los Angeles. In summer 1941, columnist Joe Oyama reported that Arthur had taken a job at the Grand Canyon in Arizona, acting as an “Apache Indian” guide. Oyama quoted Tashiro as saying after his experience in the South that “The Nisei in California talk about racial prejudice in California but it can hardly be compared with the treatment of the Negroes in the South.” Kenny Murase, writing on Nisei literature in Current Life during this period, described Arthur thus: “very interesting conversationalist; has an active, expressive face that becomes a swift-changing scene of fluid and kaleidoscopic activity.“

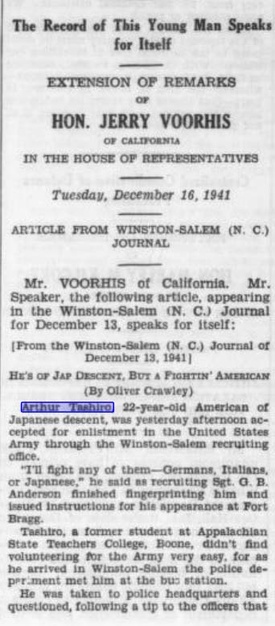

In December 1941, in the wake of the Pearl Harbor attack, Arthur sought to enlist in the U.S. Army. Although he was classified 1-A by his draft board in Los Angeles. According to a newspaper account, he faced great difficulty. Because Arthur wished to join friends whom he had made at Appalachian State, he traveled to Winston-Salem, North Carolina to enlist. However, he was arrested by local police at the bus station and taken to their headquarters for questioning. Fortunately, he was able to persuade the police of his American citizenship and his sincere desire to fight for the country of his birth and he was able to enlist. He told journalists, “They can send me to fight anywhere. I’ll shoot at any Axis Army they want me to.”

Jerry Voorhis placed in the Congressional Record an account of Tashiro’s enlistment as a sign that he endorsed Japanese American loyalty. (Ironically, within a few months Voorhis would come to support mass removal and confinement of Japanese Americans. He would serve in Congress until 1946 when he was defeated for re-election by the young Richard Nixon, who smeared Voorhis during the campaign as pro-Communist).

Arthur Tashiro served in the US Army throughout the war years. He ultimately joined the famous all-Nisei 442nd Regimental Combat Team, and served as a Staff Sergeant at Camp Shelby. In the postwar years, he attended Earlham College. He later worked for the Immigration and Naturalization Service, and he was stationed in Okinawa. Arthur died on June 9 1986. He was buried in Golden Gate National Cemetery.

© 2024 Greg Robinson