“Da Okinawan Hammah” get one skill that not too many people get. Uchinaaguchi, da Okinawan language stay dying out and Hawai‘i-born yonsei Brandon Ufugusuku Ing stay doing everything in his powah for try help save ‘em. Whether it’s teaching Uchinaaguchi classes on Zoom, creating eju-ma-cational animated Uchinaaguchi music videos for childrens, making avant-garde Uchinaaguchi movies for film festivals, or just rocking out to his own original Uchinaaguchi songs, Braddah Brandon, one Castle High School 2001 grad, does it all in da hope of revitalizing his [well, our, cuz I Uchinaanchu too] ancestral language.

[Note: Normally when I transcribe da Okinawan words I put da macron ova da vowels with da elongated sounds, but Brandon’s preference is fo use da double vowel way, so das why we doing ‘em da double vowel way for his interview.]

* * * * *

Wannee Tonouchi Lee yaiibin. Hawai nu Uchinaa yonshee yaiibin. Yutasarugutu unigee sabira.

Unigee sabira. Wannin yonshee yaiibin doo. Chuu ya majun yuntaku gwaa sshi kwimisoochi ippee nifee deebiru.

Since I stay talking to “Da Okinawan Hammah,” I figgah we gotta buss out at least some Uchinaaguchi, right? You can translate what we wen just tell?

Okay, so you said your name and you said you’re fourth generation Okinawan from Hawai‘i. And then for the second part, there’s no direct English translation, but it’s kind of like requesting good things for our time together. And so I kind of replied that I’m also fourth generation, thank you for having me and having this little chat.

Sorry, but das about all da Uchinaaguchi I know. I like ask...

(Interrupting.) Since this is for Discover Nikkei, I’m just wondering if I’m going to get a chance to talk about the term “Nikkei.”

No worry, beef curry. We get to that. For now go start by saying who you most grateful to in helping you on your journey in coming such one strong Okinawan language advocate.

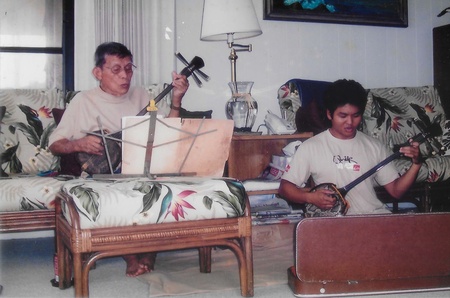

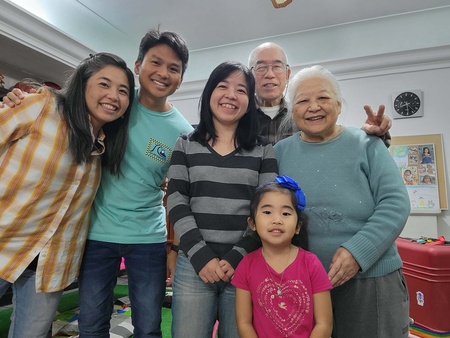

I’m grateful to my grandparents Seishun and Fumie Oshiro for making me play paarankuu drums and having me do Okinawan dance when I was a kid. My grandparents, they’re the ones that really raised me with that Uchinaanchu [Okinawan] identity.

Lotta people tink da Okinawan language stay just one dialect of Japanese, but you can try explain how das incorrect and how come you tink people tink that?

The Okinawan language and the Japanese language, linguistically they are less similar than Portuguese is to Spanish, also less similar than German is to English. And I think a lot of people think it’s a dialect, because a lot of people in Okinawa, they refer to Uchinaaguchi as “hogen.” And “hogen” is a Japanese word that translates to dialect. So I think that could be a big part of it.

This is something that stems from the forced assimilation that happened when Japan took over Okinawa and it became a prefect of Japan in the late 1800’s. They had these campaigns, you know, to wipe out the language.

What they did was in elementary schools they hit the kids with these punishments for speaking their own language, their own native ancestral language. They would have to wear this big heavy wooden placard that said something like, “I spoke hogen.” So they would get ridiculed by their own teachers telling them that their language was inferior and nothing more than a dialect.

You said you fourth generation, so das means you nevah grow up in Hawai‘i speaking Uchinaaguchi, right? So how you wen learn?

Honestly, I didn’t even know there was an Okinawan language until I was an adult. I grew up with the identity of being Uchinaanchu, like I knew that word, but I didn’t even know that that word itself comes from the language.

When I got to college I started learning sanshin, which is the Okinawan three-string lute, under Norman Kaneshiro in his class at UH [The University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa]. And that was really when I kind of realized that there’s a language, a separate language that’s not Japanese.

In 2009, when I had the opportunity to go live in Okinawa and further my studies in Okinawan performing arts, one of the extracurricular activities I did was I took an Uchinaaguchi class for residents of the city of Naha. And that’s where I guess my journey began.

The class was taught in Japanese because everybody else in that class was a Japanese speaker. So I really didn’t get a whole lot out of that class except for how to introduce myself and I also learned that my mother’s maiden name Oshiro, how it would be said in the old Okinawan way would be Ufugusuku.

I still no understand how you wen learn Uchinaaguchi, cuz so far seem like you nevah learn much.

After my study program finished, I stayed in Okinawa teaching English. I thought that when I started working at public elementary schools, the older teachers or older staff members would surely know Uchinaaguchi and would be able to teach me, but that was not the case. A lot of them would say that they could understand it, but they couldn’t speak it, or they couldn’t speak it well enough to teach me anything. Yeah, so that’s when it really kind of hit me that our language was endangered.

And it forced me to look for other ways to learn Uchinaaguchi. I sought out classes in the community, which at that time there were not a lot. But I also bought a lot of books that had recordings with them to try and learn Uchinaaguchi.

And then my journey continued when I met my wife Carolina Higa who’s actually born and raised in Argentina but was living in Okinawa at the time and we got married. Then I ended up spending some time in Argentina with my in-laws, Shohachiro and Teresa Higa.

A lot of the older generation there, Okinawans in their 60’s and 70’s, they can still speak Uchinaaguchi because at the time that they immigrated there was no forced assimilation, so a lot of them held on to their language. And because of my wife’s family I was able to learn quite a bit more from them.

Brah, I hear some people call you “Da Okinawan Hammah.” You like try explain what your nickname means?

So that word “Hammah” is a relatively new Pidgin word. A “Hammah” is like how we might say, “Oh, that guy’s da man!” It’s just someone who has the abilities. It could be intellectual abilities or it could be physical abilities. So I guess “Da Okinawan Hammah” would be someone who knows a lot about Okinawan culture. And in my case, I’m fortunate to have learned quite a bit about our language.

When in your life did you decide you wuz going make ‘em your life’s mission for promote Uchinaaguchi?

I remember when I lived in Okinawa, this was maybe a little over ten years ago, I remember telling people that you know my dream would be to one day be able to teach Uchinaaguchi to people back in Hawai‘i because at that time I was working in elementary schools in Okinawa and if I tried to say some simple Okinawan words to my Okinawan students, a lot of them didn’t even know what those basic words meant.

So that inspired me to create some songs to use in our English class at school. They were songs mostly sung in English, but the songs would explain simple Uchinaaguchi phrases and words. That’s kind of I guess the starting point because I eventually started making more songs in that style. If anyone wants to listen, those Let’s Sing Uchinaaguchi songs are available on YouTube.

For your 2016 CD Tiichi, I love how da music stay all modern and da lyrics stay all in Uchinaaguchi. I know you can play both sanshin and guitar, so I curious how come you mostly use guitar on your album?

I’ll try to throw in some sanshin here and there, but I guess you could say I use more Western instruments because I’m trying to reach a broader audience. So even if people don’t know the Okinawan words, hopefully they find the tune a little bit catchy. Even if people don't know the language, at least it might start a conversation because a lot of people don’t even realize there is an Okinawan language. And they might even repeat some of the words or maybe even look up some of the words online.

I wuz at Ukwanshin Kabudan’s Loochoo Identity Summit on O‘ahu dis past summah and you told one story about how one reporter from Okinawa said YOU no can be Uchinaanchu, Brandon! Wassup, wassup?

This reporter was interviewing me for a short film that some friends [Jesse Shiroma, Derek Fujio, Aiko Yamashiro, Yukie Shiroma, Carolina Higa, Joseph Kamiya, Hanale Bishop, Norman Kaneshiro] and I made called Chijuyaa. It was just like a short music / poetry / dance video we made for the virtual Okinawan Festival. After putting it together, I thought we gotta apply for some film festivals, we can’t just put it on YouTube. And then it got picked up by a film festival in LA and then also one in Oregon.

So this journalist, she came to Hawai‘i from Okinawa. I had seen other interviews published in Okinawan newspapers before and I noticed that in those, articles written about Uchinaanchu living outside of Okinawa, they’re always identified as Okinawa Kenkei. So I brought this up with her and I said could you please identify me as Uchinaanchu or Uchinaanchu from Hawai‘i.

I told her, it’s because when you say “Kenkei,” to me, there’s really no connection to the culture or the history or ancestry, because Okinawa Ken or Okinawa Prefecture is something that was created by the Japanese government and that’s the government that tried to wipe out our culture, our language, and our history.

And what she said kind of shocked me, and she wasn’t trying to be mean at all. She was a younger person, she herself Uchinaanchu and she told me that when she thinks of the word Uchinaanchu, she just thinks of someone born and raised in Okinawa. To her, that was an Uchinaanchu.

It didn’t really sink in when I told her that as Uchinaanchu from outside of Okinawa, we grew up calling ourselves Uchinaanchu, that’s our identity, so that’s what we want to be called. She just said, “Oh, that’s interesting. We have different viewpoints.” So of course when the article got published, it came out as Okinawa Kenkei.

Did that make you cry?

Small kine.

Now your chance Brandon. Now you can talk about how come you not particularly fond of da term “Nikkei.”

“Nikkei” is a word I had never heard growing up. Basically “Nikkei” means you’re Japanese. And for myself and I think a lot of Uchinaanchu in Hawai‘i have this similar experience, but we go almost our whole lives trying to tell people that we’re Okinawan or you know in my case, Okinawan and Chinese. Nobody argues with the Chinese part but they would always say,“Okinawan? Oh that’s like Japanese, right? Same thing.” So you spend your life defending your identity, telling people you’re not Japanese. So to call myself Nikkei, to me, it doesn’t fit.

From what I understand the word “Nikkei,” it was invented to differentiate Japanese people not from Japan from the Japanese people that are in Japan. It’s a word that separates.

So the thing about being able to call ourselves Uchinaanchu, it unifies. It’s like we’re saying Okinawans, we’re the same. Whether you’re born in Okinawa, whether you’re outside of Okinawa, whether you’re anywhere in the world, we can all use the same word, Uchinaanchu to identify ourselves. So to me, that’s the beauty of that word.

*All photos are courtesy of Brandon Ufugusuku Ing.

© 2024 Lee A. Tonouchi