Among the five accomplished children of Aijiro Tashiro, daughter Aiko was perhaps the one who had the most disparate and far-flung career, as musician, journalist, and activist.

Aiko Susanna Tashiro was born on July 2, 1911 in New Haven, Connecticut. As a girl, she moved with the rest of the family to Seattle, where she graduated Broadway High School in 1927. Later that year, she enrolled at Keuka College, a women’s college in upstate New York (where she was apparently the first Japanese American to enroll).

She was a popular student, and was elected secretary of the sophomore class. Her extracurricular activities were several times featured in the local Elmira Star-Gazette newspaper—when she headed the Decorations Committee that did up the class dining room for Colonial Day, her photo appeared in its pages! While at Keuka, Aiko joined a "deputation team" made up of students of color (an African American, a Native American, a Puerto Rican, and a Japanese woman) who together toured the region, performing concerts and speaking about racial tolerance.

Although Aiko Tashiro had started playing piano at age 8, it was during her time at Keuka that she began attracting attention as a piano soloist, performing at various events. Following her graduation in 1931, she moved to Los Angeles, near her brother Ken, and found a job as English editor of Rafu Nichi-Bei, a short-lived Los Angeles offshoot of the San Francisco newspaper.

Meanwhile, she threw herself into composing and performing music on a full-time basis. In early 1932, she performed at a farewell concert for cellist Michiyoshi Kono, who was moving to Japan. Soon after, she appeared at a Japan Night sponsored by the Southern California Music Company. She also joined the local Japanese symphony orchestra.

In April 1932, she accompanied soprano Kyoko Inouye in a recital, and in September 1932 played with Inouye and violinist Jimmy Yamamoto on a Nisei radio program broadcast over station KRKD. In spring 1932 she accompanied soprano Tomi Kanazawa in a lecture at the Barker Brothers auditorium, then in December 1932 the two performed together at a program at the Nishi Hongwanji temple. Aiko meanwhile performed a series of two-piano duets with Julia Suski. For example, in November 1932 the two played Kowalski’s “Hungarian March” together on a KRKD radio program.

In January 1933, Aiko accompanied the soprano Madame Sugi Machi in her recital at the Japanese Union Church, then in April performed at the same church alongside Madame Sugi Machi and violinist Kenshu Wanifuchi. In July and November 1933 Aiko performed mini-recitals for the Lion’s club in their regular meeting at the Biltmore Hotel. Her program included Edvard Greig’s March of the Dwarfs, works by Chopin, Rubenstein, Arensky, and Debussy, plus compositions by Japanese composer Kosaku Yamada.

In addition to performing music, in January 1933 Aiko began publishing a regular music column in Kashu Mainichi, titled “Overtones”. As she explained her first column, on January 15, 1933: “Writing about music is as simple as holding the enthused technocrat down to a 3 minute explanation of his new love. It is customary to begin by defining the subject, but consider this a departure from Hoyle.”

In the months that followed, she discussed trends in music, notably the lives of composers such as Richard Strauss, Giuseppe Verdi and Kosaku Yamada, combining a chatty style with erudition (though occasional mistakes on details—she wrote that Verdi’s opera Aida was commissioned by the Shah of Iran, not the Khedive of Egypt). She encouraged Nisei music lovers.

In February 1933, she proclaimed, “For a generous minute the playful spotlight of the Japan-Califomia Dally News focuses its rays upon the lovers of Orpheus. One knows they are legion, but their public appearances are limited, and as yet they have not banded themselves together as have the Thespians.”

In March 1934, Aiko Tashiro accompanied two colleagues in a KRKD broadcast, as part of the Japanese Cultural Broadcasting society’s weekly program. She again performed for the Lions, at a “Japan Day” event at the Biltmore Hotel with Tomi Kanazawa and Kenshu Wanifuchi. It was her last U.S. appearance for several years.

In fall 1934, Aiko sailed to Japan. Once settled in Tokyo, she took up piano study with the esteemed virtuoso Maxim Schapiro, and began teaching pupils and accompanying soloists. In October 1934, she played at a benefit for the Meguro Baptist Church. In December, she took part in a reception for the Finnish ambassador to Japan. She continued producing

“Overtones” columns, reporting on musical activities in Japan. In mid-1935, she played a series of concerts in a summer festival at Karuizawa, then reported on it for Nichi Bei. “Early June days bring the first few ‘gaijin,’ by motor or train, up from all parts of Japan. Hardly any of the shops along the machi are open. Still, there is activity afoot, or on wheels.”

In May 1936, Aiko accompanied Madame Sugi Machi in a recital at Sanshi Kaikan hall in Tokyo, then appeared at a recital of Maxim Shapiro’s students. In summer 1936 she returned to Karuizawa for another summer season. In August 1936, the Japan Advertiser reported:

“Miss Tashiro is well remembered by those who were in the resort last year for her performances at several of the summer concerts in Karuizawa….Her playing shows much skill and understanding, and her accompaniments on Tuesday evening were especially well rendered.”

Columnist Larry Tajiri noted in Nichi Bei that “Aiko Tashiro, one of the moat accomplished of Nisei pianists, is winning note in Nippon. She has given concerts in several Japanese venues and is contemplating a recital in Tokyo.”

Aiko Tashiro traveled to the United States in 1937 (by good fortune, she arranged free passage on a Japanese oil tanker) and spent the summer vacationing there. During this time, she wrote regularly for the Japanese American press. She contributed to Nichi Bei a piece on fellow pianist (and Schapiro pupil) Miwa Kai. For Rafu Shimpo, she published a humorous essay describing the living space of Nisei in Tokyo:

“Jennie has one room, with papered sliding-doors separating it from the tiny gas jet and sink which comprise the kitchenette. The sliding-doors are a last stand in winter against the icy draughts which find their unerring way through the two sliding-windows, or against the fierce sun which bakes the room in summer. If Jennie were any sort of a housekeeper. her apartment could look respectably Japanese, or passably American.”

In fall 1937, Aiko returned to Tokyo. Her activities during the next years, following the Japanese invasion of China, remain obscure. She worked as a secretary for Rev. Henry Topping, a Baptist missionary associated with the Japanese evangelist and social worker Toyohiko Kagawa. She later claimed to have taken a teaching job in the Soviet embassy in Tokyo. Her musical activity fell off, and she made only a few public appearances.

In early 1939, she accompanied the Tokyo Volunteer Choir in a performance of Handel’s oratorio Messiah. In March 1940 she participated in a broadcast of Nisei musicians on station JOAK, which was later rebroadcast in California. In Summer 1940 she toured Hokkaido and northern Honshu with violinist Temasaburo Kato and cellist Ushichi Omura. Their performances at Sendai and Hakodate were broadcast over Japanese radio. Aiko later related that she was harassed by Japanese security police during her tour. In November 1940, she performed at a dinner of the Overseas Japanese Convention marking the Emperor’s Birthday.

Shortly after this last Tokyo performance, Aiko Tashiro returned to the United States. After touring the country, she settled in Hartford—while she had left New England as a child, she continued to call herself a “Japanese Connecticut Yankee.” In an interview soon after, she noted that Japanese society had grown increasingly militarized and authoritarian, and foreign-born Japanese were the targets of suspicion. As a result, she had heeded the advice of the American embassy to depart Japan. Perhaps thinking of her teacher Maxim Shapiro, who had been forced to leave Japan, she deplored the persecution of Jews there:

“The Axis influence is beginning to be seen in the treatment of the Jews, Miss Tashiro said. Jewish travelers have great trouble with passports and visas, and Jewish residents, even those of long standing, are feeling adverse pressure. The Jews are considered a menace to the welfare of Japan, even though here are but 200 of them in the entire country.”

Aiko’s Japanese experience seems to have inspired her to involve herself in movements for peace and racial justice in the United States, using both her voice and her music. In March 1941, she delivered a lecture on Kagawa at the First Congregational Church in Meriden, Connecticut. She played in Hartford at a forum led by African American clergy on “The Negro in Hartford” which discussed ways of overcoming discrimination. In November 1941, she visited New London to play a recital, and gave a lecture on World Friendship, during which she related stories of her education and travel. (During her trip, she lectured on traditional Japanese costume before the Williams Memorial Institute!).

Aiko Tashiro, unlike her brother Ken, was not confined as a Japanese American during the war. Instead, she spent the war years in Hartford as a piano accompanist for singers and dancers, performing at several recitals at the local YMCA. She worked as a camp counselor for several summers. She was also active with the Hartford Seminary Foundation.

In November 1942, she was the guest speaker at a meeting of the Christian Endeavor Society. She sent a letter to be read at a World Day of Prayer on February 19, 1943, the anniversary of Executive Order 9066. In July 1943, while visiting her brother Aiji in North Carolina, she attended a 7-week Quaker International Seminar at Guilford College, during which she spoke and played music. In September 1944, she performed for delegates at a three-day conference at the Hartford Seminary on aiding Japanese Americans released from camp.

In fall 1944, Aiko Tashiro was hired as musician and faculty member at Bennington College in Vermont. She continued her musical and activist work. In January 1945 she accompanied soprano Ruby Yoshino in performance at an Allied Relief Ball sponsored by the Japanese American Committee of the New York War Fund, an event reported in multiple WRA camp newspapers. In May 1945, she performed at Bennington’s Second Congregational church, and spoke on Japanese American “relocation centers.”

Shortly after, she addressed the Bennington girls club with stories of Japanese-Americans, “both before the war and since they have been moved to relocation camps.” For her efforts, Aiko was singled out for praise as an outstanding, visible Nisei in the JACL pamphlet, “They Work for Victory.”

After the war years, Tashiro moved to New York. where she worked as a piano accompanist for voice and dance performers path. While she had previously described anything outside music as a “distraction,” she met a California-born Nisei, Shigeki Hiratsuka, and married him in July 1947. He would spend his career as a mechanical engineer with the Army Corps of Engineers. When the Korean War broke out, he moved to Tokyo.

During these years, Aiko remained in New York, and continued her musical activities. She played with the American Opera Youth in Washington DC, and toured as an accompanist for Marion Downs, an African American soprano from Baltimore. In the 1950s, Aiko taught piano in New York and played at dance classes at Brooklyn College. In 1951, she wrote an article for the Pacific Citizen’s Christmas issue, titled “Music is Their Way of Life,”on Japanese Americans in the music world.

In the early 1950s, Aiko moved to the Far East to join her husband, first in Japan and then in Okinawa. They returned in 1956. In later years, Aiko lived in Arlington, VA, where she cared for her husband and one son, Jon Hiratsuka. She continued to perform as an accompanist for dance classes, and to teach piano to pupils.

She died of cancer in September 1979. After her death, her family endowed the Aiko Susanna Tashiro Hiratsuka Memorial Scholarship for the Performing Arts, which provides assistance to future performers to study their craft, through the JACL.

Aiko Tashiro contributed to the musical culture of the Nisei, both by her piano playing and by her pen. Her accomplishments and cosmopolitan outlook made her a much-sought after model and ambassador for Japanese Americans on the East Coast at the end of World War II.

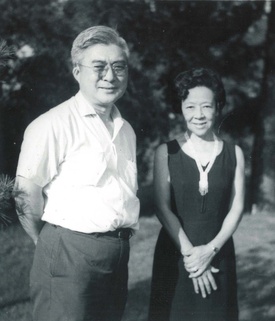

*All photos courtesy of Jon Hiratsuka

© 2023 Greg Robinson