In the 1910s, a Nikkei visitor from Hawai‘i once wrote a newspaper column expressing his surprise in running into the sons of his Hawai‘i friends and acquaintances everywhere he went in Chicago. They had come directly to Chicago from Hawai‘i without stopping on the West Coast, despite its close proximity to Hawai‘i.1 As it turns out, one of the reasons that so many Nisei living in Hawai‘i moved to Chicago and not to the West Coast was because a man named Isamu Tashiro had encouraged them.

Tashiro himself had left Hawai‘i for Chicago, which was a very popular, dream-like place for young people in Hawai‘i, and established himself as a successful dentist. He considered himself an elder among the Nisei who migrated from Hawai‘i, and felt responsible for taking care of this community, many of whom were following his path.2

When Japanese in Hawai‘i were looking for ways to provide a better education on the mainland for their children or acquaintances, they consulted Tashiro about their plans.3 His efforts, more than anyone else’s, fostered the development of the Japanese Hawaiian community in Chicago. Tashiro organized a Hawai‘i student society and the ALOHA baseball team in the 1920s, helping these Nisei not only to maintain their identity, but also to strengthen their ties as Hawai‘i Nisei in Chicago.

Early Life in Hawai‘i

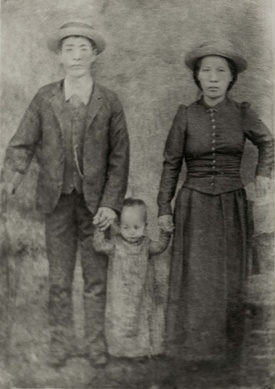

Isamu Tashiro was born in Hakalau, Big Island, in August 1895.4 Tashiro’s parents had immigrated from Hiroshima5 to Hawai‘i around 1889. They owned a small plot of land, ran a store,6 and, also engaged in the hotel business in Hilo.7

Tamotsu Murayama, a Seattle-born San Francisco-based Nisei journalist, comically described Tashiro’s childhood as follows: Tashiro “finished his primary education including an occasional banana stealing with Kanaka boys.”8

Tashiro moved to Honolulu to attend Hawai‘i Middle School9 and McKinley High School in Honolulu.10 He was well-known in Honolulu as a stellar catcher on the McKinley High School and Japanese High School baseball teams,11 and while on “Waikiki beach … he was greatly impressed with an atmosphere of international spirit.”12

Leaving Hawai‘i for the Mainland

Honolulu opened his eyes to the world, so Tashiro left for the mainland U.S. right after graduating from high school in September 1914.13 Although the boat he was aboard arrived safely in San Francisco, he was not allowed to disembark. Instead, he was sent to the detention quarter of the immigration office.

He rightfully fought for legitimate entry into California as a U.S. citizen, since he had a birth certificate issued in Hawai‘i. He urgently needed to start college in Indianapolis, Indiana, so he demanded that officials let him land and enter as a student. Luckily, his request was accepted.14

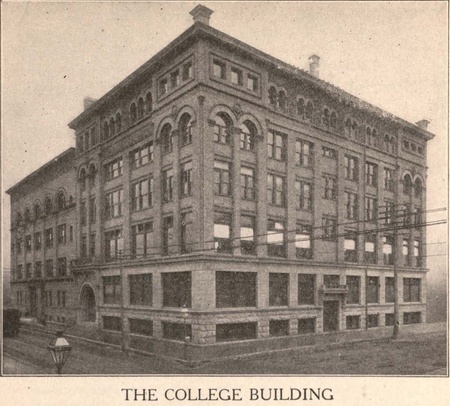

In 1915, Tashiro at first enrolled in the high school department at Valparaiso University in Indiana,15 perhaps because Hawai‘i was not yet a US State in the early 1900's. Tashiro had to complete remedial courses in order to advance to the Chicago College of Dental Surgery, which was part of Valparaiso University at the time.16 He may have come to Chicago occasionally to study at the college's campus in the hospital district of Chicago.

In the Fall of 1916 he moved to Chicago and lived at 519 Oakwood Blvd.17 By this time, he was a junior at the Chicago College of Dental Surgery.18 This college would later become the Loyola University School of Dentistry;19 Tashiro graduated from the dental school in 1918.

Playing Baseball in the Midwest

Tashiro did not lose interest in playing baseball after he left Hawai‘i and played baseball on the Valparaiso University’s baseball team, The Engineers,20 as catcher.21 One newspaper article praised Tashiro as follows: “Tashiro, the little Jap catcher was the sensation under the mask.”22

In 1916, before moving to Chicago, he also played catcher for The Knox, a baseball team in Indiana. He enjoyed being praised for being “quick-witted” and “fast playing” and for his “unusually good support” of the pitcher.23

In 1918, he joined the All Nations baseball team, a semi-professional team managed by the Chicago Exhibition Company.24 When All Nations played against the Michigan City team in 1918, it was reported that “Tashiro’s work at second base and with the stick was good.”25

As the name indicated, the All Nations team had players of various ethnicities such as African Americans, Native Americans, Japanese Americans, and European Americans. Probably as a means of emphasizing their uniqueness, the players were called “red, white, yellow, and brown perils.”26 Featuring players “from all races and nationalities” was a marketing strategy and that, according to Robert Fitts, “in a way their race was used as a commodity.”27

Tashiro also played for Chicago’s ALOHA baseball team, formed in 1922, and later a church league as well. Isamu Tashiro’s son, Wayne, said that his father once jammed his finger while catching and realized that playing baseball could affect his ability to practice dentistry. A hand injury, or the threat of it, might have been the reason that he gave up baseball.28

Opening His Dentistry Practice

After he graduated from dental school in 1918, he opened his own clinic at 3456 Cottage Grove Avenue in 1922.29 Tashiro eventually became one of the wealthiest and most popular dentists in Chicago.30 Ninety-five percent of his patients were white Americans; the remaining five percent were Japanese and Japanese Americans.31

One newspaper reported, “Tashiro first came into prominence when it was reported that he had Mary Pickford as his patient.”32 The following comical report in The Kashu Mainichi newspaper depicts what a surprise it was for Chicagoans to see the “Sweetheart of America” film star at Tashiro’s office:

Mary Pickford once gracefully sat in the chair at Tashiro’s clinic and received a fine treatment. Newspapers rushed out with ink and paper as if they had forgotten their rare treasure of gun and powder furnished by the gangsters of their own.33

Furthermore, his friendly personality and Hawaiian accent added to his charm and most certainly helped business.34 After the rumor of Mary Pickford’s satisfaction spread, Tashiro was able to charge higher fees, and even non-Japanese American patients were happy to pay for his services.35 By 1928, Tashiro had moved his office to 841 E 63rd Street and continued his successful dentistry practice in Chicago for more than sixty years.36

Establishing a Nisei Group from Hawai‘i

In May 1922, Tashiro established the Hawaiian Student Society of Chicago.37 and served as its honorary president. The purpose of the society was to foster friendship and understanding among the Nisei from Hawai‘i, enlighten them with knowledge, and cultivate and improve their morals.

In the context of starting the Hawaiian Student Society, Tashiro offered the following opinion about the status of Nisei from Hawai‘i:

Hawaii Nisei do not have a good reputation. But in Chicago they are doing well in school. I believe that Hawaii-born Nisei in Chicago, many of whom are better at school and have good morals, are somewhat different from the Hawaii-born Nisei in other areas. We are going to have five college graduates this summer and they will be medical doctors and scientists. Their school performance is excellent. Among less than thirty Nisei around Chicago, five college graduates is a significant number!38

The Society used the address of the Japanese Young Men's Christian Institute (JYMCI) on East 36th Street.39 Due to their close relationship with JYMCI, members of the Society were expected to attend Bible lectures twice a month.40 The Society also published the newsletter “Aloha ‘Oe,”41 which fostered friendship and solidarity among the members.

Manabu Mitsunaga, a dental student at the Chicago College of Dental Surgery, expressed his appreciation to Tashiro in a report to his friends in Hawai‘i, as follows:

Dr. Isamu Tashiro is our main contact and he always takes care of us very well so that we are always at ease. We have monthly meetings at his office. We were invited by many people for New Year’s Day, […] We believe we are treated nicely because they left a good impression on Hawaii Nisei for us.42

Modeling Leadership and Values

In Tashiro’s mind, the Hawaiian Student Society was part of his plan to nurture leaders. He wrote:

We are born in America, but because of our Japanese race, we cannot easily gain the socioeconomic status other Americans enjoy. We are racially handicapped. Because of that we, Nisei, have to strive first to show our goodness to other Americans. Once we succeed at that, intra- and inter-race problems will be fewer. Unless we aim to be of high character, high virtue, overcoming any bad reputation assigned us, and show how we Nisei contribute to society, we will not be given a chance to raise our heads in America.43

Tashiro himself was a very stoic person; he did not smoke or drink and he had a deep respect for Japanese customs and culture.44 According to Takayuki Asano, who was the principal of Seikei Higher School of Tokyo and had taught Tashiro at Hawai‘i Middle School, Tashiro received marriage proposals from many women, but he was determined not to marry unless the marriage prospect accepted his filial duty to his parents.45

Asano commented on Tashiro’s deeply humble manner as well:

He is very successful as a dentist and is highly respected in American society, and yet he did not hesitate to polish my shoes when I was staying at his place. I cannot begin to express my respect for such a person, who does such mundane things for others.46

The Society had arts-oriented clubs such as music, book, and theater groups, and their members enjoyed tennis, boxing, football, sumo, and other indoor sports clubs.47 The importance of sports clubs may have been based on Tashiro’s belief in the traditional Japanese value, bunbu ryodo, which recommended “excellence in both literary and military arts” as a way to make people into good leaders.

We are not sure how long the Hawaiian Student Society was active, but in May 1932, about fifty members of the Society held an annual party, with dinner and dancing, at the JYMCI.48

Notes:

1. Nippu Jiji, July 8, 1916.

2. Nichibei Jiho, April 24, 1926.

3. Maui Shimbun, August 24, 1923.

4. WWI Registration.

5. Hawaii Hochi, September 3, 1937.

6. Author’s correspondence with Wayne Tashiro, September 7, 2022.

7. 1910 census.

8. Kashu Mainichi Shimbun, July 21,1935.

9. Nippu Jiji, August 1, 1932.

10. Nippu Jiji, July 3, 1923.

11. Ibid.

12. Kashu Mainichi Shimbun, July 21, 1935.

13. Nippu Jiji, July 5, 1914.

14. Shin Sekai, August 28, 1914; Nippu Jiji, September 1, 1914.

15. Valparaiso University Bulletin 1915-16.

16. Old School Catalog 1917-18 Chicago College of Dental Surgery (Valparaiso University).

17. WW I Registration.

18. Dentos 1916; Old School Catalog 1917-18 Chicago College of Dental Surgery (Valparaiso University).

19. Chicago Tribune, December 21, 1983.

20. Valparaiso University yearbook, The Record, 1915.

21. The Torch, May 1915.

22. Ibid.

23. Knox-Starke-country-Democrat, July 5, 1916.

24. Gary Ashwill, “Isamu Tashiro, 1918 Chicago All Nations,” Agate Type (October 11, 2013); Chicago Defender, May 11, 1918.

25. Chicago Defender, May 11, 1918.

26. The Joliet Evening Herald-News, June 10, 1912.

27. Author’s correspondence with Robert Fitts, April 25, 2018.

28. Author’s correspondence with Wayne Tashiro, September 9, 2022.

29. Nichibei Jiji, April 24, 1926; 1923 Chicago City Directory.

30. Shin Sekai Nichinichi Shimbun, August 21, 1933.

31. Nichibei Jiji, April 24, 1926.

32. Shin Sekai Asahi Shimbun, May 10, 1936.

33. Kashu Mainichi Shimbun, July 21, 1935.

34. Ibid.

35. Nichibei Jiji, April 24, 1926.

36. 1928 Chicago City Directory; Nichibei Jiho January 1, 1932.

37. The Honolulu Advertiser, June 1, 1922; Nichibei Jiho May 19, 1923, May 30, 1925, and April 24, 1926.

38. Nichibei Jiho, April 24, 1926.

39. Nippu Jiji, November 29, 1922.

40. Nippu Jiji, November 12, 1924.

41. Nichibei Jiho, April 24, 1926.

42. Hawaii Hochi, January 29, 1927.

43. Nichibei Jiho, April 24, 1926.

44. Hawaii Hochi, September 3, 1937.

45. Hawaii Hochi, July 22, 1930.

46. Ibid.

47. Nichibei Jiho, April 24, 1926.

48. Nippu Jiji, June 4, 1932.

© 2023 Takako Day