Introduction

Studying the characteristics of the Japanese migratory process to Cuba in the first fifty years of the 20th century, from a holistic perspective and articulated with the migratory flows that arrived in Cuba at the same time, is a debt and a challenge for researchers. Multiple causes hinder this purpose: the absence of documentary sources, the distance in time, the lack of interest of Japanese descendants and the difficult access to information in the language of the issuing country.

Writing this brief work based on the compilation and analysis of data derived from previous research is an attempt to show some notes on the history of Japanese migration to Cuba in the first half of the 20th century, one of the least addressed migratory processes in historiography. regional and Caribbean. It is also an invitation to researchers to delve into the historical experience of Cuba as a host country, since its discovery in 1492, of different human groups, including the Japanese, who have shaped its ethnic profile, its identity and its culture.

This monument was donated by the Sendai Ikue Guken School and inaugurated on April 26, 2001. The sculpture is located next to the entrance channel of the bay of the city of Havana. (Photo by the author)

Notes for a history of Japanese migration to Cuba (1898-1958)

The year 1868 was transcendental in the histories of Japan and Cuba 1 . For the first it was the beginning of the so-called Meiji Renewal (1868-1912), with significant innovations in the social, economic and political spheres, aimed at modernization. For the second it was the beginning of a long period of war that lasted thirty years in order to achieve the abolition of the slave system and independence from Spanish colonialism.

Cuba, since its discovery, was characterized by welcoming people or population groups from various places in the world, which determined the formation of its national identity and its cultural development. In the opposite direction, Japan, closed for centuries to contact with other countries and to the foreign mobility of its citizens, arrived at the 19th century with an ethnic homogeneity that typifies its identity and culture.

The Japanese modernization process involved opening to the Western world. To do this, its policy was based on the fifth article of the Letter of Oath of 1868, which stated: “Knowledge will be sought throughout the world to consolidate the knowledge of imperial rule” 2 . That is why the advice of foreign experts and the sending of Japanese students was encouraged, especially to Europe and North America.

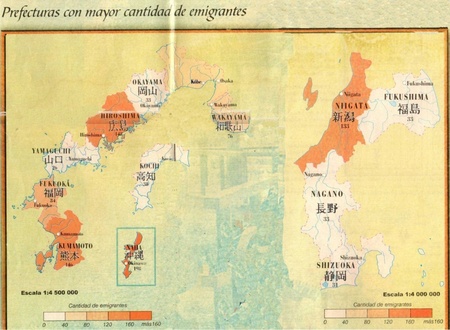

The set of transformations brought about a broad migratory process from rural areas to urban centers that could cause serious social friction and the Japanese government decided, as a strategy, to send its surplus population abroad, through free emigration or of government agreements to the Asian continent, to the Pacific islands, to the United States and Canada; in 1897 to Mexico, in 1899 to Peru and in 1908 to Brazil.

The Japanese presence in a general sense was not well received by the native populations, so its reception was prohibited from 1924 to the United States, then to Canada and Australia. The Japanese government was forced to redirect its migration plans to Latin America during the 1920s and 1930s 3 . The Caribbean and, especially, Cuba, could have been the object of his attention, since the sending of Chinese to it was known since the early days of the 19th century.

The development of the war against Spain, plus the intervention of the United States in the war conflict in 1898 4 turned Cuba into an unfavorable enclave for its population migration plan, much more so when the defeat of Spanish colonialism concluded with the North American military occupation. of the island as of January 1, 1899.

At the time when the direction of the national-liberation objective of the Cubans was being discussed with the negotiations between Spain and the United States, the Japanese Pablo Osuna 5 arrived in Havana, on September 9, 1898, with intentions of settlement. ship from Mexico, everything seems to indicate that it was free and by its own decision. Their arrival has been taken as the starting point of Japanese migration to Cuba. Already in 1899, eight Japanese were recorded living in Cuba, seven men and one woman.

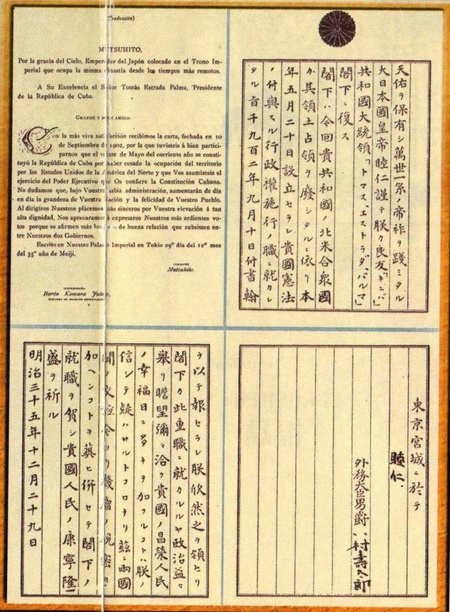

The republic that was born on May 20, 1902 in Cuba is strongly tied to the United States by the ties of neocolonialism. Although Japan 6 recognizes the newly created Cuban government, the complex economic panorama, the result of thirty years of war, together with the unstable political and social situation, as well as the intervening power of the US authorities in the country, hindered the establishment of an understanding between both.

Thanks to the peculiarities of the neocolonial status of the Republic of Cuba, a powerful American investment process is fostered, especially in the sugar sector, which makes it a privileged place in the Caribbean economic field and, incredibly, its attraction as a source of Progress reaches remote places in the country of the Rising Sun, favorably impressing those who craved easy enrichment for a quick return to their homeland.

Since the early days of the 20th century in Cuba we have had contracting agents for Japanese braceros 7 whose fares were paid, in whole or in part, by the Japanese government or by North American sugar companies based in Cuba. For example, Keitaro Ohira, settled in Havana since 1905, an agent of the Oversea company, frequently traveled to Japan in search of Japanese farmers to work as macheteros in the Las Villas and Camagüey power plants; We also have Tomishiro Ogawa, who does it starting in 1916 for the Constanza power plant in Cienfuegos.

In Japan, fabulous stories were told about Cuba 8 , either by those first Japanese who were there and returned to their country, or by letters from those who had settled here and asked for their family and friends to accompany them on their promising journey. future. In Cuba, it was said, there was wealth due to the rise in the price of sugar due to the First World War and the absence of hostile feelings towards foreigners, in contrast to the expressions of nativist hysteria found in other countries against Asians, who suffered discrimination. social and legal in the receiving countries.

Despite the strong restrictions established by the North American government regarding Japanese migration in these first years of the 20th century and the close relationship of the Cuban government with the United States, Japanese citizens arrived, generally salaried rural laborers, to work in the industry. sugar industry from different regions of Japan, from Okinawa to Hokaido 9 , even from the United States and Latin America.

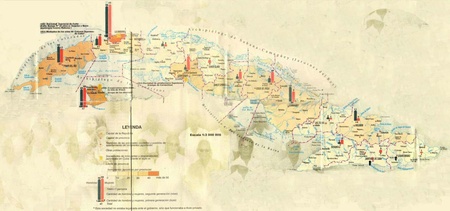

The 1920s of the 20th century were the scene of the largest wave of Japanese immigration to Cuba 10 . The main ports of entry were Havana, Santiago de Cuba and Cienfuegos. Supported by the economic problems and the requirements of labor immigration in the country, which led to the enactment of immigration laws favorable to the importation of labor, the children of the Rising Sun arrived within the group of Antilleans, Europeans and Asians who made up the cheap labor market of the time.

They entered legally, or sometimes illegally, as desirable or undesirable braceros and under different types: the pioneers, who traveled at their own expense and who for the most part did not arrive directly from Japan; those who traveled due to the subsidy of the Japanese government, at the call of relatives and friends; or by contractors related to Cuban or North American sugar companies.

Later, immigration through letters of invitation or under the concept of family reunification would be incorporated; The entry of “brides and grooms by letter” or by “catalog” was also facilitated, through the intermediation of their families or companies that were dedicated to this purpose.

The great mass of Japanese immigrants was almost always located in the sugar mills of the central region of the country. They were to remain there for three months and then agricultural colonies would be promoted, but that was not the case, the lands were never given to them, they were only assigned to cutting cane as macheteros and they quickly found themselves covered in debt.

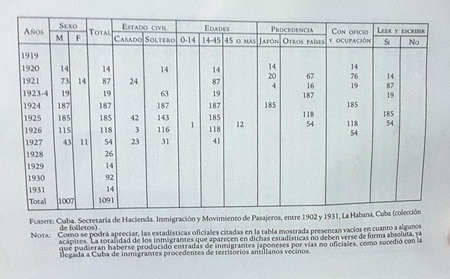

In a short time there was a process of desertion among them due to the difficult working conditions, the intense heat and the problems with the payment of salaries. Many began to explore new horizons in other places in the country, which caused them to wander throughout almost all of Cuba 11 , in a fan movement whose epicenter was the center-southern of the island, which ranged from Matahambre in Pinar del Río to Guantánamo. It is estimated that there was representation of Japanese migrants in the six former provinces of the country and already in the early 1930s it is proposed that there were around 1,091 native Japanese 12 .

The struggle for subsistence was intense and traumatic in a country that was suffering the consequences of the great economic depression of 1929, with the price of a pound of sugar on the world market at less than two cents a pound. But nothing stopped them and they remained for years alone or dragging their families, traveling in both rural and urban spaces, performing the most dissimilar jobs, with an unusual dynamic, compared to that of other immigrant groups existing in the country, but also discriminated against by poor people and also by Asians.

To be continued...>>

Quotes and Notes:

1. When Christopher Columbus touched Cuban lands on his first voyage to discover the American world, he believed he had arrived in Japan (Zipango) in 1492.

2. Bonifazi, M. (2009). “ Japan: Revolution, Westernization and Economic Miracle ”, Japanese Observatory of Economy and Society . Vol 1, No.5 (May 2009).

3. Inés Sanmiguel (2006). “Japanese in Colombia. History of immigration, their descendants in Japan”, Journal of Social Studies , April 23, 2006, pp. 81-96.

4. In 1898, the Maine, a North American warship, exploded in Havana Bay, killing five young Japanese who were part of the crew who acquired knowledge about the navy to later apply it in their country. This event is taken as a pretext by the United States to declare war on Spain. Data provided by Mercedes Crespo, Cuban researcher on Asian issues, 2017.

5. Rolando Álvarez and Marta Guzmán (2002). Japanese in Cuba. La Fuente Viva, Fernando Ortiz Foundation, Havana, p. 13.

6. In 1906 letters of representation were not accepted and in 1907 the Cuban consul Enrique Ramsden was not received. Japan's negative attitude is explained by the fact that it did not recognize representatives of an occupied country. In 1908, the representative of the second American intervening government in Cuba closed the consulate in Yokohama.

7. Álvarez and Guzmán. Japanese in Cuba, pp. 15 and 55. See The Japanese presence in Cuba: Centenary of the beginning of relations between Cuba and Japan , 2002, Fernando Ortiz Foundation, Ediciones GEO, Havana (folding).

8. Jaime Sarusky (2010). “The Japanese, a journey without return” in The Two Faces of Paradise , Ediciones Unión, p. 89.

9. R. Álvarez. Op. Cit., pp. 25, 26, 32 and 33.

10. See tables in Álvarez and Guzmán, Japoneses en Cuba , pp. 25 and 26.

11. Jaime Sarusky (2010). “The Japanese community on the Isle of Youth” in The Ghosts of Omaja , Ediciones Unión, Havana, p. 38.

12. Álvarez and Guzmán. Japanese in Cuba , pp. 24 and 26. Author's note: From the Island of Cuba it was divided into six provinces and the Isle of Pines as part of the archipelago. Already in 1976, a new administrative political division was produced that constituted it into fourteen provinces and a special municipality on the former Isle of Pines, now called the Isle of Youth.

© 2020 Lidia Antonia Sánchez Fujishiro