THE OUTBREAK OF WAR

I bid farewell

to the faces of my sleeping children

As I am taken prisoner

Into the cold night rain— M. Ozaki1

In 1941 there were 158,000 people of Japanese ancestry living in Hawaii, 37 percent of the population. Ninety-four thousand lived in California, but they constituted only 1 percent of the population.2 There were 25,000 in the states of Washington and Oregon, with a total of 285,115 in the 1940 U.S. Census.3 On December 8, 1941, the day after the attack on Pearl Harbor, 736 Issei were arrested by the FBI. Within a week, more than two thousand Issei on the U.S. mainland and Hawaii deemed to be “suspicious” on the basis of the FBI’s secret intelligence were detained in camps operated by the Immigration and Naturalization Service.4 In Hawaii martial law was declared, and those considered “subversive” were interned at Sand Island and Honouliuli.

Authorized by President Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066, General De Witt established more than one hundred prohibited zones within the West Coast region and proclaimed the entire West Coast as well as southern Arizona as a restricted zone in which all Japanese Americans had to abide by travel restrictions and curfew laws. A key member of the Western Defense Command, Col. Karl Bendetsen stated: “I am determined that if they have one drop of Japanese blood in them, they must go to camp.” The public policy of mass incarceration was directed solely at persons of Japanese descent, despite the fact that America was also at war with Italy and Germany. Moreover, Japanese Hawaiians were never subjected to mass incarceration, although Hawaii was more susceptible to invasion.

The Supreme Court, charged with the duty of protecting citizenship rights, succumbed to public pressure. Seven of the nine justices were appointees of President Roosevelt. Justice Frank Murphy acknowledged, “Today is the first time, so far as I am aware, that we have sustained a substantial restriction of the personal liberty of citizens of the United States based upon the accident of race or ancestry.”

In late February of 1942, all Japanese Americans were removed from Terminal Island, California, by the Navy. A month later, to gain experience in the logistics of removal, the army moved Japanese Americans off Bainbridge Island, Washington. Sixteen temporary quarters were set at fairgrounds, racetracks, and other facilities in Puyallup, Washington; Portland, Oregon; Marysville, Sacramento, Tanforan, Stockton, Turlock, Salinas, Merced, Pinedale, Fresno, Tulare, Santa Anita, Manzanar, and Pomona, California; and Mayer, Arizona. Meanwhile, permanent barrack-style quarters were being established in Tule Lake and Manzanar, California; Poston and Gila River, Arizona; Minidoka, Idaho; Topaz, Utah; Heart Mountain, Wyoming; Amache, Colorado; and Jerome and Rohwer, Arkansas. A civilian agency, the War Relocation Authority (WRA), was established to administer these camps. Euphemistically called relocation centers by the government, President Franklin D. Roosevelt referred to them as concentration camps. Most of the internees in the Immigration and Naturalization Service Centers were Issei, joined by a few thousand immigrants from Mexico and Latin America. In total, the internees in all of the camp numbered over 120,000. Betrayed by their government, Japanese Americans became the victims of racial and wartime hysteria. Under the false premise of military necessity, Japanese Americans were singled out, uprooted from their homes, and confined in the internment centers. Not a single case of espionage was ever attributed to the Japanese Americans.

BEHIND BARBED WIRE

We lived one family to a unit, four units to a barrack, with knotty walls separating us from our neighbors. There was little privacy. Furtive love affairs were conducted in the shadows of barracks and in empty officer rooms. Family quarrels were stifled and swallowed. The latrines were the worst: rows of toilets back to back, one long trough for washing, a shower room with six shower heads. The modest met each other coming and going in the early hours of the morning.

— Wakako Yamauchi5

What was life like in the camps? The ten War Relocation Authority (WRA) camps were located in forbidding areas that were too hot during the summers and both muddy and freezing during the winters. Each block of a dozen or more barracks had a central mess hall, laundry, toilets, and showers. Food costs were limited to forty-five cents a day per person but soon a large part of the food supply was grown in the camp fields maintained by the internees. At Manzanar, inmates cultivated three hundred acres within four months. They constructed an irrigation system, planted corn, cucumbers, tomatoes, radishes, and melons, and revived some of the orchards nearby. Soon they were shipping surplus crops to the other camps.

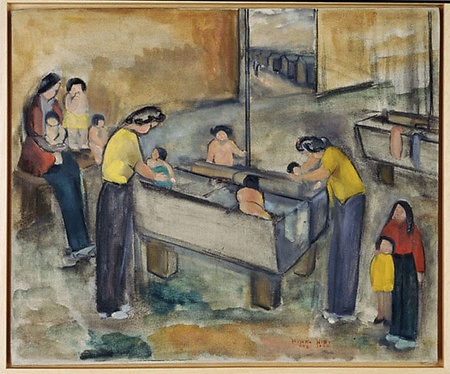

The internees organized and operated cooperatives. All necessary jobs—such as office workers, barbers, garbage collectors, firemen, doctors, janitors, and farmers-were quickly allocated. Wages were low, ranging from twelve dollars per month for menial laborers to nineteen dollars per month for professional such as doctors. The average wage was sixteen dollars per month. The work setting created anomalous situations. Journeyman doctors, for example, worked under less experienced Caucasian counterparts earning much more pay. Successful farmers were reduced to manual labor on the camp farms. For artists, ironically, incarceration brought some advantages. It provided them with compelling subject matter and the time to paint. Art schools were quickly organized and creative activities flourished.

The War Relocation Authority, as a means to control the internees, imposed a paternalistic self-governing structure which favored the second generation, which had not yet assumed leadership in the prewar communities. Camp administrators banned the use of Japanese in camp meetings and placed the Americanized Nisei into positions of responsibility, widening the generation gap.

Resistance in the WRA camps began within a few months. It took the form of strikes, riots, and beatings, and even the assassination of those who were suspected of informing to the authorities. The internees were factionalized by differing strategies of whether to cooperate with or resist the WRA authorities. In Poston the conflict escalated from beatings to arrests and a major strike. In Manzanar soldiers killed two internees when protests escalated into a major confrontation. Other forms of resistance tactics included the posting of anonymous flyers that protested injustices, work slowdowns, hunger strikes, stealing, defiance through gambling, the distillation of spirits, and other forbidden acts. And, most important, messages of protest appeared in poetry and art.

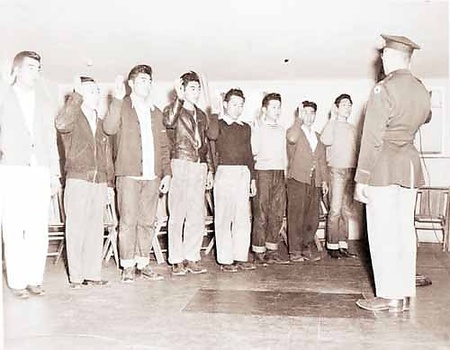

The circumstances under which the internees lived led to conflict. The army’s decision to induct Nisei into the 442nd, an all-Japanese American combat team only exacerbated the situation. To separate the loyal from the disloyal, the army instituted a questionnaire. Male citizens were asked: “Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty, wherever ordered?” and “Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attacks by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor or any other foreign government, power or organization?” This brought mixed responses from the internees.

After the draft was reinstated, resisters in the Heart Mountain camp organized the Fair Play Committee, maintaining that they should uphold American democracy at home and resist the denial of their constitutional rights. The three leaders of this movement were sent to the Tule Lake camp which became a segregation center for the “disloyals.” Subsequently, sixty-three men who refused induction were given a mass trial and sentenced to federal prisons for three years. A total of 267 men were convicted of draft evasion and sent to prison.

Under these circumstances, it is amazing that some one thousand young men in the internment camps volunteered for service in the armed forces of the United States. About eight hundred of them were accepted. The Japanese American Citizen’s League (JACL), founded in 1930 by a group of Americanized Nisei, lobbied for the formation of an all-Japanese American unit that would enable them to prove their loyalty. The league urged the Nisei to cooperate with the army when the draft was reopened. It is ironic that the Nisei felt compelled to volunteer to serve in segregated units “to defend democracy” while their families remained incarcerated.

When Tule Lake Camp became a segregation center, many of those answering yes to both questions on the loyalty questionnaire were moved to other camps or left the camps for the Midwest and the East. The Nationality Act of 1940 was amended, making it possible for the internees to renounce their U.S. citizenship and to take the ultimate step of “repatriation” to Japan. Yet, fewer than 5 percent of the internees left the camps to return to Japan at the end of the war.

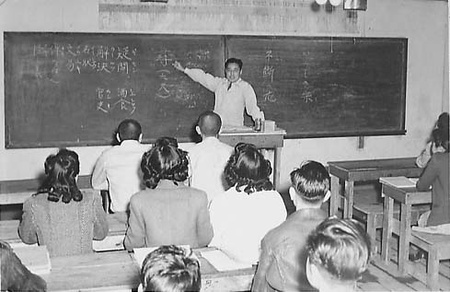

The camp communities exhibited resilience, persistence, and strength. The internees established schools, hospitals, and police and fire departments. Churches flourished, with their multitude of activities. The internees joined singing, dancing, flower arrangement, doll making, wood carving, bonsai, and poetry clubs. Adult education included classes in dress making, design, English, psychology, photography, journalism, and technical areas. For children and teenagers, there were various activities during school classes and after hours: clubs, socials, dances, and sports such as baseball, football, and basketball.

POSTWAR: REDRESS AND REPARATIONS

Japanese Americans began to leave the camps and to reintegrate into the larger society as early as 1943. In the postwar period, the Nisei were able to make great strides in fields that had previously been barred to their parents and themselves, such as civil service, education, and law. Their reentry into society provided the impetus for re-asserting the rights which the U.S. government had abrogated during the war. The campaign for redress and reparations officially began in the 1970s when Japanese Americans call upon the United States government to acknowledge a wrong, to correct the record, and to require that the Constitution of the United States and the Bill of Rights be applied equally to all. The Commission on Wartime Relocation and internment of Civilians (CWRIC) was established by Congress in 1980 to study the internment of Japanese Americans. The commission was charged to review the facts and circumstances surrounding Executive Order 9066. Issued February 19, 1942, and the impact of such an order on American citizens and permanent resident aliens. The commission’s charge also included the review of directives of the United States military forces that led to the relocation, and in some cases, detention of American citizens including Aleut civilians and permanent resident aliens of the Aleutian and Pribilof islands, and to recommend appropriate remedies.

The hearings of the commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians began in Washington, D.C., on July 14, 1981, and continued throughout the summer and fall in Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, the Aleutian and Pribilof islands, Chicago, and New York. At these hearings Japanese Americans presented hundreds of written and oral testimonies on the Japanese American concentration camps. On August 10, 1988, House Resolution 442 was signed into law by President Regan. It provided for individual payments of twenty thousand dollars to each surviving Japanese American internee and a 1.25 billion dollar educational fund, among other provisions.

Redress and reparations, however, are not the end of the internment story. There all still stories waiting to be told. Let all the voices be heard: the Issei who are still alive, the Nisei, Kibei, and Sansei, the resisters, veterans, and renunciants. We need all of their voices to discover and understand fully the story of the Japanese American internment.

The internment is a story of the reaffirmation of an ethnic culture in our multicultural society. It is a story of oppression, resistance, and the ability of a people to challenge their circumstances. It is a story captured by artists whose canvases reflect the emotional impact of removal and imprisonment, feelings of shock, dismay, and sorrow. In the work of Japanese American artists who were interned, we discover panoramic views of camp and wilderness, and feel the harsh wind, sand, and heat that were part of the environment. The artists also provided us with intimate views of day-to-day life: meals in the mess halls, work and leisure—all through periods of outrage, terror, and joy. Life did go on, despite the barbed-wire enclosures.

Yes, it’s right that we’re here

to see first hand where

18,000 of us lived

for three years or more

to see again

the barbed wire fence

the guard towers, the MPs

the machine guns, bayonets

and tanks, the barracks

the messhalls, the shower rooms

and latrines.I wish I could share

the feelings I have now

with the Issei and Nisei

they who lived here

they who do not speak of it

who pass it off

as a good time experience.Whatever we did here

the commitments we made

loyal or disloyal

compliance or resistance

yes or no

it was right!

Because they young people

make it so because they seek the history

from those of us who lived it.— Hiroshi Kashiwagi6

Notes:

1. M. Ozaki, in Jiro Nakano and Kay Nakano, editors, Poets Behind Barbed Wire (Honolulu: Bamboo Press, 1984), 86-87.

2. Takaki, Strangers, 379.

3. David O’Brien and Stephen Fugita, The Japanese American Experience (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991), 137.

4. Sucheng Chan, Asian Americans: An Interpretive History (Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1991), 123.

5. Wakako Yamauchi, The Christian Science Monitor, November 8, 1988.

6. Hiroshi Kashiwagi, “A Meeting at Tule Lake,” in Kinenhi: Reflections on Tule Lake (San Francisco: Tule Lake Committee, 1980).

*This article was originally appeared in the exhibition catalogue for The View From Within: Japanese American Art from the Internment Camps, 1942-1945 in 1992, which was published in conjunction with the exhibition organized by the Japanese American National Museum, UCLA Wight Art Gallery, and the UCLA Asian American Studies Center at the Wight Art Gallery October 13 through December 6, 1992, to commemorate the 50-year anniversary of the Japanese American incarceration.

© 1992 Japanese American National Museum, the UCLA Wight Art Gallery, and the UCLA Asian American Studies Center