Author’s note: Summer is festival time for Japanese Americans, who honor the memories of their ancestors with prayers and folk dances, with taiko drumming and rice dishes. I republish this blog post each year in honor of my late parents, grandparents and family spirits. It’s a reminder of what is most important in life, beyond the next quarterly earnings release.

WATCH VIDEO: The Nisei Week Festival 2010 in the "Little Tokyo"

district of downtown Los Angeles >>

Hard to believe. But 75 years ago, my late mother and aunt as young teens performed Japanese dances on these same streets. Their spirits are strong. Video courtesy of RafuShimpoOnline on YouTube.

THE QUEST TO better one’s life is universal. Leaving rice farms and their loved ones in Meiji era Japan, my grandparents boarded ships to the United States before the first Ford Model Ts rolled off the assembly line. Like the legendary industrialist Henry Ford (photo: right), Japanese American entrepreneurs had business in their blood, and blood in their business. My grandfathers and grandmothers raised a flock of kids, grew fruits and vegetables on leased land, ran a store near “Little Tokyo” in downtown Los Angeles. Despite legal barriers and brutal discrimination, Japanese Americans rose in the agricultural and florist industries, and launched restaurants, metal shops, tofu factories, commercial fishing firms, and other small businesses.

THEIR SAGA REFLECTS the spirit and work ethos of all U.S. immigrants and their kin, from 19th-century Irish laborers to 21st-century India-born entrepreneurs. In our modern U.S. economy, immigrant-owned startups churned out $52 billion in sales in 2005, according to research by Vivek Wadhwa, Ben Rissing, and Gary Gereffi at Duke University and AnnaLee Saxenian at the University of California at Berkeley. For old-schoolers who like digging through voluminous yet enriching history, my late uncle Masakazu Iwata, a UCLA scholar and Biola University dean, wrote about Japanese American farmers in Planted in Good Soil: A History of Issei in United States Agriculture (Peter Lang Publishing, 1992).

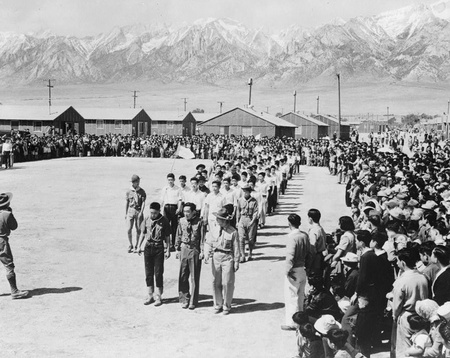

MY FOLKS LEFT their store and farm work when World War II struck. How do you value that economic loss? While uncles served honorably in the U.S. Army, 19 family members—nearly all U.S. citizens—were bussed to the Manzanar military internment camp in the high desert of California. On work leaves from camp, my late father toiled in potato and sugar beet fields in Idaho and Oregon, and in the produce market in Chicago. My late mother, a speedy typist, whipped out letters as a secretary for the U.S. War Relocation Authority. Aunts contributed to the war economy by making camouflage nets. How do you measure that productivity? They kept on. They persevered. Seven times down, eight times up, goes the old Japanese folk saying.

"Manzanar Boy Scout Memorial Parade" by Frances Stewart of the War Relocation Authority, U.S. Department of the Interior, via Wikimedia Commons.

AFTER THE WAR, Japanese Americans scattered throughout the Western U.S. I grew up in South-Central Los Angeles, a cultural fusion over the decades of middle-class European Americans, black migrants from the South, and Latino immigrants. The once-thriving Japanese American enclave in the Crenshaw district—with its down-home sushi joints, summer festivals, and obon folk dances—was a cultural sanctuary and an economic hamlet for Japanese American small businesses. But it died long ago, as my generation found the suburbs, middle-class jobs, and interracial marital bliss. The early waves of Japanese immigrants and their entrepreneurial drive symbolize the vast ethnic and demographic forces growing stronger by the day in the U.S. Those same forces are cascading worldwide, transforming cities, nations, the economy. The local tales and global story are playing out on millions of like stages.

IN A RITE of passage, I spent part of my early career tracing the family arc, hounding my parents for shards of their personal histories. Spring pilgrimages to the windswept Manzanar site. A trek to Japan, to Buddhist temples and family farms in the green hills of Wakayama and Okayama. Closure came with President Reagan signing the historic redress bill in 1988 that gave each interned Japanese American $20,000 for what legal scholars call the greatest civil rights violation in our nation’s history. A generation of economic dreams deferred, though not killed. During pilgrimages, Grandma always brought cool water to the Manzanar cemetery. The spirits are thirsty, she told my aunt. Beyond the politics of identity, my soul-searching and dusty boxes of documents honored the ghosts and their legacies. It was time to move on.

"Cemetery shrine, Manzanar Japanese internment camp" by Daniel Mayer, under a Creative Commons license via Wikipedia.

*This article was originally published on Edward Iwata’s blog, Cool Global Biz, on July 12, 2013.

© 2013 Edward Iwata