Twenty-five years have passed in what seems only a few moments: the Little Tokyo years of VC. Its founders pragmatically called it Visual Communications, Southern California Asian American Studies Central, Inc. in 1971 after a humble birth in the living room of photographer Bob Nakamura, where the first project emerged as an ingenious modular exhibition of the camps for the JACL “Visual Communications” committee. A cadre of dedicated media workers grew through a succession of offices from the Seinan district on Jefferson to Silver Lake and eventually to San Pedro and Boyd downtown.

Like a favorite movie seen years ago, some scenes now seem more vivid—while others are fading. The “movie” of VC in Little Tokyo has been an epic with enough location shifts and characters to keep the most jaded viewer intrigued. There have been love stories, comedy, enough tragedies to last a couple of lifetimes, and some nail-biting suspense: about whether a non-profit community media arts center could survive the good, the indifferent, and the hostile times.

We came to Little Tokyo through the doors of VC at the end of the ’70s—John, looking for new adventures after teaching middle school, an eager UCLA grad student in film recruited by Prof. Nakamura to volunteer on a real shoot over Spring break. Amy was fresh from East Asian Languages at USC where her true interests were in film-making. Recruited for her language skills, she assisted Nancy Araki as a casting assistant and liaison to Little Tokyo’s Japanese speaking community on VC’s landmark production, Hito Hata: Raise the Banner.

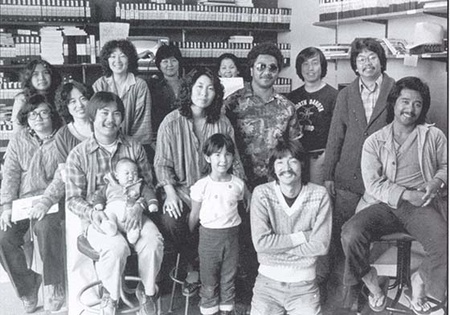

VC of the late ’70s was a thriving production center in Little Tokyo, funded by the U.S. Office of Education to produce videos about Asian Pacific Americans. The VC office was a 3,000 square foot loft at the northwest corner of San Pedro and Boyd, on the third floor of the Field Company, a large-scale hat factory. There were video and film editing rooms, a photographic darkroom, and an unequalled archive of Asian Pacific historical photographs gathered in the course of several projects. A spacious graphics area served several community groups, and there was even a big International Harvester truck parked outside on Boyd affectionately known as “the Blue Bomber,” as handy for lunchtime hops to Boyle Heights as it was for production.

More than a dozen staff would sit in a large circle to debate for hours the plot points in scripts about Issei living in Little Tokyo’s residential hotels or Pilipino manongs organizing farm laborers or Samoan college students struggling with funding cutbacks. For Hito Hata, historic Little Tokyo was literally recreated. The small VC crew wrangled hundreds of extras and closed down First Street on a Friday night to shoot an entire Nisei Week Parade from the mid 1930s, complete with kimono-clad dancers, kendo groups, farmers on festooned floats, and a Charlie Chaplin look-alike as grand marshal. With the help of community-minded actors such as Mako, Yuki Shimoda, Pat Morita, Saachiko, and Hiroshi Kashiwagi, Hito Hata was completed in 1981.

Hito Hata, directed by Nakamura and Duane Kubo, completed a trilogy of Japanese American life, begun in the mid-’70s with Bob’s tribute to the Issei, Wataridori: Birds of Passage and Duane’s portrait of the band, Hiroshima, Cruisin’ J-Town. But VC was also the leading edge for other Asian Pacifics in media. Linda Mabalot, longtime Executive Director who passed away this past May, began working on the documentary, Manong, in the late 1970s and was instrumental in transforming Carlos Bulosan’s Pilipino American novel, Quiet Thunder, into film. And members of the South Bay Samoan community were an integral part of the production of Vaitafe, a drama about recent Samoan immigrants.

While the VC crew ventured out on location, the late Charlotte Murakami managed the office, firm in her admonitions to complete our chores before we rambled out to Elysian Park to softball practice. Steve Tatsukawa, then the Executive Director, was lead prankster, trading suit and tie for an aloha shirt and Mickey Mouse baseball cap, smoking up a cloud—always cracking you up with an offbeat take when least expected.

In 1981, VC partnered with the National Coalition for Redress & Reparations (NCRR) to videotape the L.A. hearings of the Commission on Wartime Relocation & Internment of Civilians that were held in the State Office Building at Broadway and First. A VHS recorder was borrowed to economize the twenty-six hours of coverage, and everyone from directors to interns took shifts videotaping—no matter what their experience. In 1998, VC and NCRR once again partnered to preserve the deteriorating, original VHS tapes, digitalizing and making them available to the public.

As the 1980s progressed, arts funding across the country declined dramatically as conservatives gained power in government. The VC staff reluctantly questioned whether “to fight or fold.” Many staff reluctantly departed to secure employment or start families, and VC dwindled to a core group of Nancy Araki, Linda Mabalot, and distribution specialist John Rier. Tatsukawa had become program director at KCET but continued to advise the staff, and Board President Doug Aihara played an increasing role in VC’s survival. We continued as part-time volunteers. Operations were moved to a small office on the third floor of the Japanese American Cultural & Community Center where community groups were given a rent subsidy.

The challenges became even more formidable with the sudden death of Steve Tatsukawa in 1984 at age 35. A brilliant strategist and beloved community activist, Tatsukawa’s passing was mourned across the nation and his funeral at Union Church drew one of the largest gatherings witnessed in Little Tokyo. Despite this major loss, the years at the JACCC were distinguished by several significant achievements. The L.A. Asian Pacific Film & Video Festival at the Japan America Theater (JAT) was begun in 1983 and a collaboration with Nisei veterans started in 1984 with the co-sponsored premiere of Loni Ding’s documentary, Nisei Soldier. Also in 1984, Little Tokyo: One Hundred Years in Pictures, written and edited by Mike Murase, was published by VC in collaboration with the Little Tokyo Business Association. It commemorated the centennial of Little Tokyo and is still sought after by Asian American students, teachers, historians, and scholars. The mid-’80s also witnessed the birth of ChiliVisions, VC’s unique “film-n-food” fundraiser that initially was met with much skepticism by the VC board, but which is now in its 16th year.

When the rent subsidy at the JACCC ended in 1987, VC moved to the 3rd floor of the Rafu Shimpo Building at Los Angeles and Third. The Japanese section of the Rafu was still typeset by hand and we would observe from our door the typsetters running up and down the stairs to the 2nd floor editorial offices. Located as we were on the outskirts of Skid row, we survived burglaries, car break-ins, thefts, and a mugging. The hostile environment did not, however, deter the many aspiring film and video makers who were drawn to VC’s innovative workshops and classes.

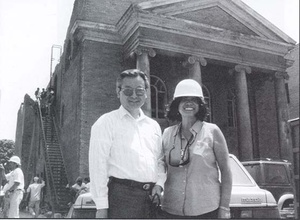

1997: Bill Watanabe, Exec. Director, LTSC, and the late Linda Mabalot, Exec. Director of VC, at Old Union Church as renovations were begun to convert to Union Center of the Arts, the permanent home of Visual Communications.

VC finally came home to its present location at Union Center for the Arts in 1998. In the early 1980s, architect and community leader Tosh Terazawa envisioned renovating the Old Union Church, an historic site built in 1920 which had been closed in 1979 when the congregation moved to San Pedro and Third. The East West Players Theater had worked on fundraising to renovate the building but with limited success. In 1990, Bill Watanabe of the Little Tokyo Service Center and Lisa Sugino of the CDC (Community Development Corporation) approached VC with the prospects of a space in a renovated Union Church. It was a longstanding dream of Linda’s that VC would be able to purchase its own building, and she agreed that VC would serve with LTSC as a general partner for the Old Union Church Partnership with East West Players and LA Artcore as tenants. In 1997 ground was broken for VC’s permanent home.

The roots of VC obviously extend deep within the history of Little Tokyo, its staff through the years having witnessed, documented, and participated in many of the significant events in this community’s storied past. The passing decades have seen changes in the organization, its technological tools and the surrounding landscape, but the one constant has been the idealism and commitment first expressed by the founders of VC to present accurate, sensitive, informed portrayals of Asian Pacific Americans in the media. That was the idea that captivated us back in our idealistic youth—and which continues to infuse today’s youthful, idealistic staff.

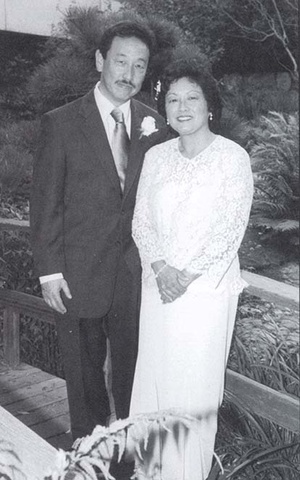

The year 2003 has been one of particularly dramatic changes. Sadly, in May of 2003, Linda Mabalot succumbed to a battle with lung cancer shortly before her fiftieth birthday. Before her passing, she asked us to marry at a VC event, having known of our long relationship that began with our meeting at VC twenty-three years before. In her honor, we were finally married this past October. That our marriage was integrated with a fundraising event for VC is an indication of our deep feelings for this special place—and our confidence in its future.

As our wedding invitations noted:

“Over the past two decades we’ve worked, played, shared struggles and triumphs at VC with a group we’ve come to think of as family. Our marriage on this day signifies our re-commitment to each other and to the organization that has been such a large part of our lives.”

*This article was originally published in Nanka Nikkei Voices Little Tokyo: Changing Times, Changing Faces, in January 2004. It may not be reprinted or copied or quoted without permission from the Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California.

© 2004 Japanese American Historical Society of Southern California