Rear Part 1 >>

Can you give me a rough chronology of your career path?

I stayed briefly in Mio (about one month) and went to Tokyo and got a job with the U.S. Occupation Forces at Haneda Air Base. The job came with housing (barracks type) and we could eat at the G.I. Mess Hall, so it was very comfortable. The housing was not good. The heating was poor and there was no hot water, but at that time, I still felt fortunate with what I got.

I worked for the Occupation Forces for about four years and was not making much progress on the job and the passing of time made me feel that the future lay in the civilian world. One of the officers suggested that I go for an interview with a Japanese businessman that he knew, on the proviso that I do not tell the commanding officer about the recommendation. He was afraid the commanding officer would not look too kindly upon anyone having anything to do with my leaving, but we did not have to fear. The commanding officer was very understanding and he told me that unlike military personnel, he had no power to promote me and thinking of my future, he readily agreed that I should try my luck elsewhere.

At this point, around 1950, my life in Japan really started. Up to then, working for the Occupation Forces, I was in a very protected environment with food and housing provided, but leaving the Occupation Forces meant trying my luck in the real world.

Through this interview, I got a job with an American company that imported food and daily essentials which were sold to the foreign community in Japan. Military PXs served the military personnel and dependents and civil service personnel of the occupation forces, but there was a niche market for foreigners non-related to the Occupation and the company was serving this market. The company joined with a department store and opened a store in Osaka and they assigned me to the Osaka store as their representative.

As time went by and the Peace Treaty was signed, the Occupation Forces started to return buildings and homes they had taken over. The main store and head office building of our department store partners had been taken over as the PX, but when it was returned, they re-opened the main store and our partnership dissolved, but I was asked to stay on with the department store, which I did.

Throughout all this time, aside from my regular job, I was asked by friends or friends of friends who needed English language help in running their businesses. It was a time when there was a scarcity of people with useful English knowledge. Although like most Nisei at that time, my English and Japanese were limited, but to some of my friends, there was no one else available. It was a situation sort of like, “If you don’t know electricity, a candle is a pretty good thing.”

I tried to accommodate everyone who approached me for help. There was a case where I was helping a man with his business letters and one day he received a cable that his New York customer wanted to telephone and talk to him and asking what day and time he should call. He called me at my office at my regular job and we set up a time when I could sneak out of the office and take the call. When I answered the phone on behalf of my friend, the New York customer wanted to talk directly with my friend. I told him that he does not speak or understand English too well; the New Yorker insisted that he writes English so he must understand. Of course, I had to explain to him that I wrote the English, etc. before we could start the conversation.

Digressing a bit, at that time the availability of good interpreters and translators was very limited. I think that we were fortunate that although most of us were employed by the Occupation Forces, it was not as interpreters, but since we could speak English, we made good employees for non-Japanese speaking military personnel. Of course, at times, we had to act as interpreters, but not on a full time official basis since the military had trained personnel for that purpose.

Soon, when the economic situation improved, many Japanese friends became successful businessmen and they wanted to hire me on a full time basis. I had a number of choices and of course, they knew me so well that I did not have to go through the customary tests to join any company.

From the department store, I went to a medium-sized trading company to work in their textile export division. Quite frequently, I was asked by the parent company, a spinning mill which had bought technology from an American company and I was sent on loan to help in the contract negotiations and the transfer of technical expertise. This experience was of great help later when while still an employee of the trading company, I was moonlighting with another company that was trying to buy technology from overseas.

After leaving the trading company, I joined a company making expendable supplies for business machines. It started as a carbon paper and typewriter ribbon manufacturer progressing into more sophisticated products for high tech business machines, including word processors, bar code printing machines and computers.

The company invented the thermal transfer media (printing medium) used in word processors and bar code printers. I was involved in licensing this technology to a U.S. company in Buffalo, New York and a French company in Nantes, France.

The company had subsidiaries in the U.S.A., Hong Kong, Malaysia, and United Kingdom and I was involved in one form or another in all of its overseas businesses. My work entailed a lot of travelling to North America and Europe. During the height of my career, I was off to some foreign country once every two months.

I travelled so much that I have two passports which ran out of pages and had to have pages added. This was in the days when, unlike now, I had to have my passport stamped each time I entered or left the country.

The president of the company was a long standing friend of mine and he liked to tell people that the interview took 17 years and we could not find anything wrong with each other so Tak joined the company.

My final position with the company was as managing director, in charge of overseas operations and upon reaching retirement age (65) they asked me to stay on as an advisor to the company which I did until I finally retired when I was 78.

Can you tell us a little about your family?

I have three daughters and six grandchildren. The eldest daughter has two boys, the second daughter has a daughter and a son and the third daughter has two daughters. The oldest grandson finished university and is working now whereas the youngest granddaughter is just starting her second grade in elementary school.

What are some things that you want young Canadian Nikkei to know about the experience of Nisei who ‘returned’ to Japan after WW2?

I hope they will remember the reason why the JC Nisei were sent to Japan and that they will work to ensure that something like that will not happen again not only to Japanese Canadians, but to other minorities as well in Canada.

When forced to live in a “foreign” country, language, customs, food, etc. can make things unbelievably difficult. Even for Nisei with the advantage of racial origin, the conditions in Japan were so severe that I think many never could adapt. Although I have lived in Japan for so long, at times, I still get the feeling that I am not completely used to the country.

Any bitterness?

Not now.

How do you define yourself now?

I have a Canadian Passport and a permanent residence visa for Japan. I don’t travel as much now, but when I was still working, I used to go back and forth between Japan and Canada/USA. On one occasion when I was clearing through immigration at a Canadian port, the official quipped, “So you do come back once in a while.” On the other hand, although there is a permanent residence visa stamped in my passport, I have to obtain a re-entry permit before I leave Japan in order to come back in. (This might finally change soon.)

Any advice for younger Nikkei about the value of their Japanese roots?

My parents taught me to be hard working and diligent in whatever I do and I think those traits were Japanese, but I don’t think that the Japanese have a monopoly on those values.

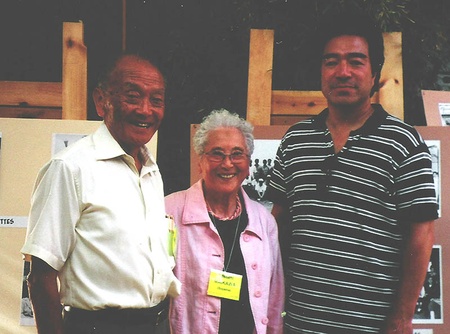

L.C. Reunion Aug. 16, 2007 at the Momiji Seniors Centre. From left: Taku Matsuba, Susan Maikawa, and Norm Ibuki.

© 2014 Norm Ibuki