“Instead of a long-running and bloody battle with nature, to dominate her, we can walk in step with a tree to release the joy in her grains, to join with her to realize her potential, to enhance the environment of man.”

— George Nakashima

“The wood is our muse and our palette; its shapes and colors speak to those who listen.”

— Mira Nakashima

Mira Nakashima is the author of the new book The Nakashima Process Book which provides a window into the design traditions of her late father, famed woodworker George Nakashima. Mira has dedicated herself to continuing both the craft and legacy left by her father, who Time Magazine has called the “foremost master of his craft.”

Published in September 2023, the book is the culmination of a multi-year project to give a wider audience a “deeper understanding of what makes Nakashima unique.” It was my privilege to meet Mira in New Hope, Pennsylvania at the Nakashima Woodworking Studio. We discussed her family’s story and her father’s life, work, and legacy.

Continuing her Father’s Legacy

Mira is a lively, animated, and incredibly warm woman of 81 years who has lived in New Hope since about the age of three. Her professional biography includes degrees from Harvard and Waseda University in Tokyo, where she learned Japanese “by full immersion,” she says with a laugh.

She maintains a full schedule of travel. She had just been in Mexico before we spoke and was heading to Japan the following week to check on the factory there. Mira currently serves as the President and Creative Director for George Nakashima Woodworkers Studio and the President of the Nakashima Foundation for Peace.

Mira remembers her father as a master artist whose work was his life. George had a love and reverence for trees for as long as she can remember. This translated directly to how he treated the wood in his work. He aimed to unlock the potential of each piece of wood and provide it with a second life as an heirloom to pass on to future generations.

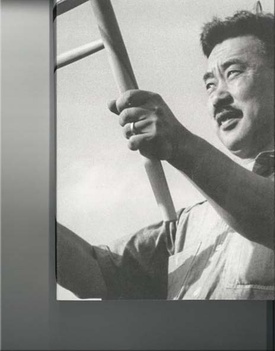

Pre-War Years

Mira tells how her father, a child of the Great Depression, became an adventurer in the early 1930s. After losing his job, he sold his car and bought a round-the-world steamship ticket. He spoke of those years fondly, especially the year he bummed around Paris.

He then married Mira’s mother Marion and settled in Seattle. There, he met Morris Graves, a painter also influenced by Eastern aesthetics. They were so close that Morris paid the hospital bill for Mira’s birth, as her parents had very little money.

George Nakashima did not establish his furniture business in New Hope, Pennsylvania until 1943. That’s because his family, along with more than 120,000 Japanese Americans, was incarcerated during World War II by decree of the U.S. government.

Wartime Incarceration

Then six weeks old, Mira has little to no memory of living behind barbed wire. Despite that, she has ongoing bone issues that were directly caused by her time at the Minidoka War Relocation Center in Idaho.

Meanwhile, much of her father’s strength came from his ashram studies in Puducherry, Indiain the mid-1930s. Mira’s father maintained a dedication to the practice of inner peace that he learned there. Her own name also comes from Mira Alfassa, then the Ashram’s Director.

Mira emphasizes that her family was lucky compared to other Nikkei imprisoned during the war. Not only did they stay in Minidoka for a shorter duration than others, but she and her extended family of grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins were able to stay together.

Minidoka was located in the desolate prairie flatlands of south-central Idaho. Many incarcerees forged social bonds by writing Japanese poetry, farming, and playing baseball. Others, like Mira’s father, collected the woody shrub known as greasewood or bitterbrush and carved and made small objects with it.

George also innovated pieces that made camp life more livable. These include a coal storage box that doubled as a bench; a wood baseboard that joined two small cots to form a larger bed; and a table that folded up against the wall when not in use. He was fortunate to work alongside the master carpenter Gentaro Hikogawa, a fellow incarceree who had trained in Japan.

Early Release

Fortunately, Mira’s family was sponsored by George’s former supervisor Antonin Raymond, for whom George had previously worked in Tokyo. For this reason, Mira and her parents were released from Minidoka after little more than a year to travel to Pennsylvania.

Despite this, they were still deemed “enemy aliens” and had limited employment options as George was banned from working in architecture. During the Second World War, construction projects were solely done through contracts with the U.S. Government. As a Japanese American, George didn’t qualify.

George, a trained architect with degrees from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and other prestigious institutions, was relegated to a menial job as a chicken farmer when he arrived at the Raymond Farm in New Hope. Mira laughs remembering her father saying, “Chickens and I are not psychologically compatible!”

Unlike many Nikkei who lost their household items, the Nakashimas were lucky that their friend Morris Graves stored their belongings. Mira recently found letters from Graves to her mother about keeping their household goods and car and figuring out ways to store them.

Neither parent talked much about their imprisonment. However, George wrote in his 1981 autobiography The Soul of the Tree: A Woodworker’s Reflections, “The incarceration I felt at the time was a stupid, insensitive act, one by which my country could only hurt itself. It was a policy of unthinking racism.”

Yet he set aside these issues and devoted his life to creating beauty. Mira explains that his resilience, perseverance, and strength during this time came from his faith. He never discussed the scars from these years, although he probably had many.

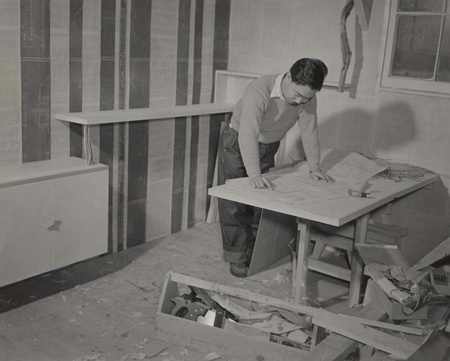

Woodworking Studio Opened

Mira emphasizes that relocating to New Hope was much better than being behind barbed wire. George called the move a “new hope” for all of them. Mira’s father saw this name as prophetic of their new life, full of hope and promise.

So it was in New Hope that her father opened his woodworking studio in 1943. The family was happy to find a huge emphasis on the arts in this small town that was, and still is, filled with many artists.

Mira’s mother served as the studio’s bookkeeper and business manager. Mira explains, “My father was her employee! She never worked alongside him with the wood. When Dad wrote his book [The Soul of the Tree], she tried to edit it, but threw up her hands in despair, as she was an English major!”

Unique Woodworking Philosophy

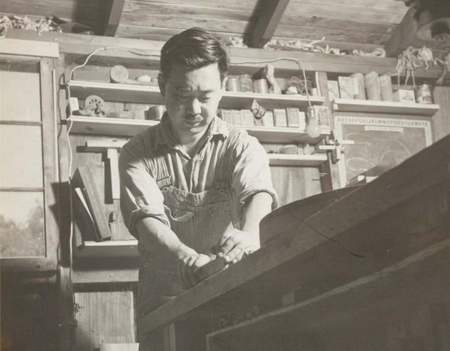

The unique woodworking philosophy that George created included the tenets of shibu, or the astringent and tautness of the form; wabi, or the spareness of the materials used; and sabi, or the rustic appearance and elegant simplicity of the finished furniture.

George also embraced the Japanese belief of kodama, or the “spirit of the tree,” which aligns with the Nakashima philosophy. He wrote that it “refers to a feeling of special kinship with the heart of a tree. It is our deepest respect for the tree...that we may offer the tree a second life.”

Another fundamental belief is to treat wood “with the respect due to other living beings.” He also firmly believed that each piece tells its own story that the woodworker must unlock so the furniture takes on “a life of its own.”

Selflessness in woodworking is a final tenet George learned from the Integral Yoga School and Yogi Sri Aurobindo. The woodworker must sublimate the ego to a higher purpose. They must not impose their ego or artistic methods upon the wood. For example, cracks in the beautiful boards are not filled but remain exposed for the user to admire.

Understanding Trees

A lot is written about the concept of “forest bathing” and the health benefits of being in nature and among trees. These scientific findings align with both the traditional importance of trees in Japan and the Nakashima philosophy.

Mira believes few people understand trees like her father did. She says, “You have to work with what you are given and the shapes that the tree decides to be and the colors that it decides to be, rather than imposing your ego and your sense of shape or something on a piece of wood. The piece of wood is your partner.”

She continues, “It’s really important that we realize these beings that are sharing this planet are actually very instrumental in preserving it and shouldn’t be just destroyed like they have no reason to be here.”

George also believed in the “soul of the tree.” Mira writes that the trees “certainly have vibrations and you can feel them…There is some kind of communication between human beings and wood and we try to preserve that when we make our furniture.” When clients come into the studio to choose wood, they often say that one piece speaks to them over another.

The Studio Today

By the early 1970s, Mira began to work alongside her father in the studio. After her father’s passing in 1990 and her mother’s passing in 2004, she took over their respective responsibilities. Her husband helps manage the studio now.

Mira continues to design. She also plays the guitar and other instruments. She has even collaborated with the world-famous Martin Guitar Company nearby to design a one-of-a-kind commemorative Nakashima guitar in recognition of her father’s legacy. This was personal for the guitar company since George worked closely with them when it came to milling lumber on the property at Martin Guitar in Nazareth, Pennsylvania.

Sustainability was also key to her father‘s work. Currently, an arborist cares for their well-being. The arborist does not harvest trees unnecessarily but waits until the end of their lives to harvest them or he collects fallen trees.

The more than 8-acre property is now a cultural landmark. In 2014, the National Park Service recognized the property as a National Historic Landmark. The World Monument Fund has also designated it as a World Landmark.

Mira is also proud of the Nakashima Foundation for Peace. The idea came to George in the 1980s after gallbladder surgery. He had a vision to make large wooden Altars for sites across the world, funded by donations from people worldwide to promote world peace. Currently, there are tables in New York at St. James Cathedral; Moscow, Russia in the Academy of Arts; and Southern India at the Auroville Ashram.

Continuing George’s Legacy

Mira and the other woodworkers try to stay true to her father’s legacy and keep his practices alive. Many have worked there for years. Even today, they ask, “What would George do? Would he be happy with what we are doing today?” Staying true to her father’s way of woodworking is deeply important to all. She continues to lead the studio’s design team.

Mira wants her father’s legacy to be “the continuation of our work and philosophy far into the future, including sustainable harvesting of trees and respecting that material.”

I highly recommend reading her wonderful new book.

* * * * *

Find out more about the life and legacy of George Nakashima:

- The Woodworkers Studio

- The Nakashima Foundation for Peace

*Process Book is available for purchase through her website and the JANM Museum Store.

I would like to express my gratitude to Mira Nakashima for allowing us to spend an afternoon with her to immerse ourselves in the Nakashima Woodworking philosophy. I hope that I have done justice to George and Mira Nakashima and the Nakashima legacy.

© 2023 Tai Bickhard