Decades ago, when I was studying for my degree in journalism, I had an extremely tough professor. He was a gruff, cynical curmudgeon who constantly berated us for failing to scrutinize any statements made by politicians, government officials, and others in power. “When interviewing them,” he advised, “always, always, ALWAYS bring your bullsh*t detector with you.” I got a “B” for that class (my first “B” ever in school), mainly because I wasn’t adept at investigative journalism. I couldn’t always see through people’s artful dissembling, convenient half-truths, and outright lies. In other words, my bullsh*t detector needed a serious recalibration.

Since then, throughout my more than thirty years in the publishing industry, I would always hear my professor’s voice whenever I was duped into believing someone — a business exec asserting that his failing company wasn’t perilously close to bankruptcy, a government official claiming no ulterior motives for her agency’s decisions, a scientist touting the results of fudged research. And I usually think of my professor when I encounter a euphemism like “workforce rightsizing” (i.e., employee firing) or “enhanced interrogation” (i.e., torture).

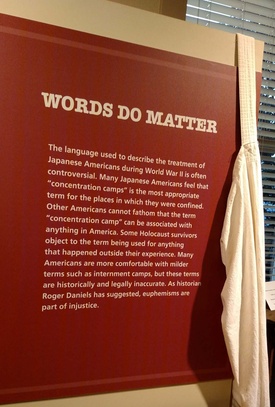

Of course, euphemisms aren’t necessarily bad, and many are useful for softening the blow of something painful or unpleasant — she “passed away” (instead of died) or he’s “between jobs” (instead of unemployed). And for that reason I believe that I’ve subconsciously been reluctant to let go of certain euphemisms used during World War II.

I don’t want to think of my Nisei mother and her family being incarcerated in a concentration camp on Arkansas swampland. Instead I much prefer imagining her being comfortably “interned” in a “relocation camp.” But those types of euphemisms do tremendous damage by obfuscating and minimizing the egregious injustices suffered by our community during that time.

As such, I have continually reminded myself of the need to deploy more accurate language in my writing and, over the years, I thought I had been relatively successful in eradicating the usage of deceitful euphemisms. But then, recently, I came across a report written by Atsushi Archie Miyamoto, a Nisei man who, like my mother, had been aboard the MS Gripsholm in an exchange of civilians between the U.S. and Japan during WWII.

Many people, even Japanese Americans, might not be familiar with this ugly chapter in U.S. history. Just to recap: After the Pearl Harbor attack, borders were quickly shut down between the United States and Japan, stranding thousands of civilians who found themselves stuck in enemy territory. These included U.S. businessmen in Japan, as well as many U.S. missionary families in China and other parts of Asia then occupied by Japan. It also included Japanese nationals, such as Japanese businessmen and their families, who were stuck on the West Coast and other parts of the United States.

So the initial goal to repatriate those individuals was ostensibly humanitarian. The problem, though, was that there were far more Americans stuck in Asia than there were Japanese stuck in the United States. So, somewhere in the offices of the U.S. government, it was decided that Issei men and their families would be included in the exchange to even the body count. (Note: The Densho website contains an excellent summary of the two Gripsholm exchanges.)

Whenever I’ve read government documents about the exchanges, I’ve bristled at the use of the term “repatriation,” which might have been an accurate description for the Americans stuck in Japan, Shanghai, Hong Kong, and other parts of Asia, but it certainly wasn’t true for my Nisei mother who somehow found herself on a ship to Yokohama. She was a U.S. citizen by birth who had never been to Japan. The only country she could have been repatriated to was the United States. That aside, I had gotten accustomed to the government’s use of the terms “diplomatic exchange” and “civilian exchange” to describe how my mother and her family ended up in war-ravaged Japan during World War II.

But in Archie Miyamoto’s detailed report, he rejects those words and instead uses the term “hostage exchange,” which at first took me aback. I just couldn’t fathom the idea that my mother had been a hostage. The more I thought about it, though, the more I realized that that, in fact, was what she was.

In essence, she and her family had been shipped from their home in Honolulu to a concentration camp in Arkansas, where they were held captive, and then they were exchanged for U.S. citizens who had been held captive by Japan. So, yes, she was a hostage of the U.S. government, used as barter to secure the freedom of Americans incarcerated by Japan.

My mother was 16 years old when the actual exchange of hostages occurred in Goa, India, in October 1943. Like many Nisei, my mother rarely talked about the war, but the one thing that stayed burned in her memory was the way in which the trade took place. Like cattle, the hostages held by the U.S. were exchanged one-for-one for the hostages held by Japan, with a long line of people from one side having to pass a long line of people from the other side. In my mother’s teenage mind, it did not escape her notice that she, a U.S. citizen by birth, was being traded for another U.S. citizen but of a lighter skin.

My mother passed away ten years ago, and I think she would have objected to the term “hostage exchange” to describe her traumatic experience during WWII. In her mind, the word “hostage” would probably conjure up images of airplanes being hijacked, banks being robbed with people held at gunpoint, and children of wealthy parents being kidnapped. But stripped of any anodyne euphemisms, that is what she was. With my bullsh*t detector on full blast, I reject the terms “diplomatic exchange” and “civilian exchange,” and I now say this: My mother was a hostage.

© 2023 Alden M. Hayashi