Ever since I could remember, a large, colorful tapestry of the Great Torii of Miyajima was displayed prominently in the living room of my Nisei parents’ house. Visitors couldn’t help but notice it when they entered our home in Honolulu. As a kid, though, I never thought much about that artwork; to be honest it was like wallpaper that was always silently there, unnoticeable in the background of my youth. Over the years the tapestry became badly faded from exposure to the brilliant Hawaiian sunlight, but my parents always kept it there, a permanent fixture in their living room. Only after my parents passed would I finally realize its deep emotional significance.

Although my parents were both born and raised in Honolulu, they had met in Japan after World War II and were married there in the early 1950s. My father was in Japan because he had traveled there from Hawaii to attend his grandfather’s funeral. In contrast, the reasons for my mother’s presence in Japan at that time were far more complicated.

During World War II, my mother and her family were shipped from Honolulu to a concentration camp in Arkansas. From there they were then sent on a ship to Japan in a hostage exchange: the U.S. wanted the return of Americans who had been stuck in Shanghai, Hong Kong, Singapore, and other parts of Japan-occupied Asia when the war broke out, so in exchange it sent hundreds of Nikkei, including my mother, who was a U.S. citizen by birth, to Japan. This was in 1943, during the middle of WWII. My mother and her family ended up living in Iwakuni, the town next to Hiroshima, and they were there during the atomic bombing two years later.

My parents rarely talked about the past, and as a young kid I learned that there were many topics too taboo to discuss. As such, I resigned myself to just accepting what I didn’t understand—all the huge gaps in my knowledge of who my parents were before they became my parents. I never understood, for example, why my mother was always so worried about her health, with any slight change in her body of such profound concern. As a young child I had no idea that she worried for decades about cancer because of any potential exposure to radiation that she might have suffered from the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

I also didn’t understand why my parents talked so differently from each other, my father in the heavy pidgin of the Islands while my mother spoke in perfect English, even enunciating certain words like “issue” with a British pronunciation (“issyu” instead of “isshu”). Another peculiar thing in our household was that my father used the shared bathroom in the hallway, along with my three brothers and me, while my mother alone used the bathroom off her and my father’s bedroom. I guess I just assumed that her bathroom was the “women’s restroom” and ours was for males. Only later as a teenager would I learn that married couples typically share their en suite bathrooms.

So many family mysteries that I would slowly unlock throughout my adult years, especially after I began to uncover more of what my parents, especially my mother, had endured during WWII. I learned, for instance, that at the Jerome concentration camp in Arkansas there was sometimes friction between the Nisei from the mainland versus those from Hawaii, with the former teasing the latter about their unrefined, crude-sounding pidgin English. I also found out that there were no private bathrooms at Jerome, only communal showers and latrines. Worse, the toilets were in rows with no stall dividers.

With such knowledge, I could understand why my mother spoke such proper English, even though she was born and raised in Hawaii, and I felt such compassion for her insistence on bathroom privacy, even from her own husband. But I still had so many other family mysteries that I couldn’t quite explain.

Unfortunately, both my parents suffered from dementia in their final years so, although they became more willing to talk about their past, their memories would often be suspect. On the same afternoon when I visited my mother who was then in an assisted-living facility, she talked about how she had helped me to get settled in Los Angeles when I first moved there for college, and she told me she had had another child (in addition to my three brothers and me). I know for a fact that the first memory is false (I moved to L.A. by myself) but was the second memory also faulty, or did she miscarry or have a baby that I knew nothing about?

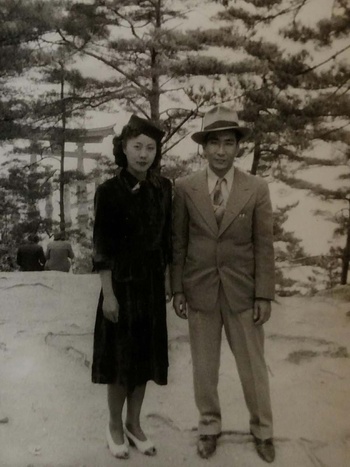

After both our parents had died and my brothers and I were cleaning out their house before putting it on the market, we discovered shoeboxes filled with so many photos that we had never seen before. In one black-and-white image, which must have been taken in the early 1950s, you can see the Great Torii of Miyajima in the distance, just to the left of my mother and father.

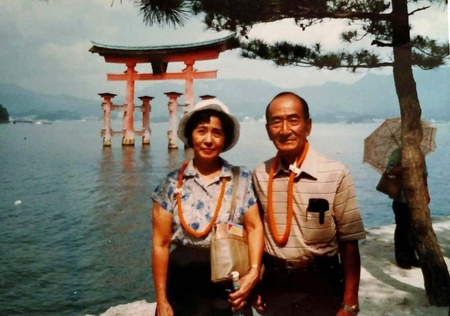

And then, almost 50 years later, my parents would essentially take the same picture, but this time in color.

After seeing those photos I realized that that tapestry in our living room wasn’t of some beautiful random scene in Japan. There was some deeper meaning there. Was Miyajima where my parents went on their first date, after having been introduced by a nakodo, or matchmaker? Or maybe Miyajima was where they spent their honeymoon before moving back to Honolulu?

As an engineer who later became a writer, I find that the two sides of my brain are often at odds with each other. The left, logical side of me wants cold, hard facts and rational answers, whereas the right, emotional side prefers to let my imagination take flight. That uneasy tension is usually there whenever I try to make sense of the myriad memories I have of my parents, all in hopes to one day arrive at a coherent story that can explain those many mysteries.

Yet, over the years, I have come to the sad realization that, when it comes to my parents, I may never be able to fill in all those gaps in my knowledge. And a more sobering thought: I may never even know just how much I don’t know. So in my novel, Two Nails, One Love, this is what I wrote: “The next day, Dad took Mom on a ferry to Miyajima, a small island just off the coast of Hiroshima. There, in the early evening, with the waning sunlight striking the giant red torii, or ‘floating’ gate, in the shallow waters just off the coast, he proposed and Mom accepted.” And this, now, has become my own “memory” of that beautiful tapestry that was once so prominently displayed in my parents’ living room.

© 2023 Alden M. Hayashi