One crucial aspect of Nikkei history that has not received due recognition from community chroniclers is the close relations between Japanese Americans and blacks, and especially the disproportionate support that African Americans offered Nisei during the World War II period.

In past columns, I have discussed the efforts of such outstanding figures as Hugh Macbeth, Loren Miller, and Howard Thurman to defend the rights of Japanese Americans. The activism of Black women was less visible, but arguably even more impressive, given their doubly marginal position in society. Such figures as lawyer Pauli Murray, scholar Edmonia White Grant and journalist Erna P. Harris, to name just a few, found ways to support Japanese Americans.

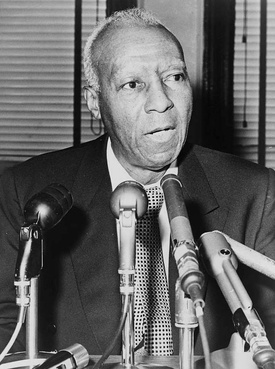

Perhaps no black woman was more eloquent in her defense of equality than Layle Lane, a New York-based educator, union leader, and newspaper columnist. Sensitive to the economics of racial and gender discrimination, especially in education, she provided powerful and insightful testimony in favor of fair treatment for confined Japanese Americans and recognition of the essential nature of their struggle for the survival of democracy.

Layle Lane was born on November 27, 1893, in Marietta, Georgia. She was the fourth of five children of Calvin Lane, a Congregationalist minister, and Alice Virginia Clark Lane, a teacher. Her father built the family house in Marietta, and established a church and school nearby. Following a threatened lynching, the family was forced to flee, first to Knoxville, Tennessee and then to Vineland, New Jersey.

Layle Lane graduated from Vineland High School, then entered Howard University. Unable to find a job after her graduation from Howard, she went on to earn a bachelor of science at Hunter College, and also attended Columbia University Teachers College, receiving her MA in 1919. She was hired as a social studies teacher, working at Benjamin Franklin High School and James Monroe High School in New York City.

Even as she pursued her teaching career, Lane grew interested in the Haitian Revolution and spent time living in Haiti. In the late 1920s, she took over a farm in Doylestown, Pennsylvania, and named the property La Citadelle—a nod to the fortress in Port-au-Prince that played a key role in the Haitian revolution. Beginning in 1929, Lane transformed La Citadelle into a camp where she hosted inner-city youth from Philadelphia and New York.

Meanwhile, Lane threw herself into writing, public speaking, and political activism both within black communities and in mainstream circles. In the mid-1920s, she began speaking at Citizens’ Forums sponsored by the Citizen’s Welfare Council of Harlem. In 1927 she presented at a Negro Labor Conference in New York. In 1934, Lane was appointed the first woman and first African American vice president of the teachers’ union American Federation of Teachers, a position that she would hold for a decade.

During the Depression years, Lane led efforts to unionize Southern black teachers—many of them women—who faced inferior pay and work conditions compared to their white counterparts. During these years, Lane became active in the Socialist party. She ran for elective office on the Socialist ticket, including three times for Congress, though she did not come close to winning.

In 1941, Lane joined famed labor leader A. Philip Randolph’s March on Washington Movement, with the goal of organizing a giant demonstration against racial discrimination in Washington DC. In exchange for calling off the March, they won a commitment from President Franklin D. Roosevelt to sign an executive order in June 1941 banning employment discrimination in war industries and creating the Fair Employment Practices Committee. Lane was part of the delegation of four, led by Randolph, that went to Washington in June 1941 and worked with government officials to hammer out the contours of the order.

In fall 1938, Layle Lane was granted a one-year sabbatical from public school teaching. During this time, she made a contract to contribute to the African American newspaper New York Age. Her column, titled “Land of the Noble Free,” began appearing late that year (just months after the debut of a fictional counterpart, the intrepid journalist Lois Lane, in the Superman comic books).

Meanwhile, Layle Lane set up plans for a bus trip across the country. The trip gave Lane her first chance to visit the Western United States, and brought her into contact with Japanese Americans, as she reported in her columns.

In her March 20, 1939 column, she compared her impressions of public markets in New Orleans, San Antonio and Los Angeles, and concluded that the latter was nicest, because Japanese farmers predominated there:

The faults of the Japanese imperial government are by no means those of the Japanese famers in California. They are hard-working, efficient and extremely kindly in their dealing, I have heard a few complaints that like most merchants they are ready to take advantage of a customer, but there was little evidence of any shady practices. Most produce is so reasonable in price that one would have to be a skin flint (sic) to complain.

Even after her trip, Lane remained attentive to the presence of Asian Americans. In January 1941, she spoke with pleasure of visiting International House in Chicago, where Black students lived and worked. “Conversation with a Japanese, a Filipino and a young girl from Georgia indicate that in the setting of the International House is an opportunity to realize in a small degree its program. Through personal association, people of all different backgrounds, races and creeds may learn to understand each other”

Following Tokyo's attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Lane asserted that the Japanese action mirrored past depredations of white imperialists in China and elsewhere in Asia: “The Japanese attack is portentous not only of the smoldering resentment of the darker world, but also of the efficiency with which this same darker world may use the method of imperialistic aggression.”

While she had previously opposed U.S. intervention in the war like other Socialists, she now insisted that with the declaration of war, African Americans would do their part to defend the nation, like other citizens: “We Negroes are as much America as the signers of the Declaration of Independence of the Constitution; therefore, its ideals are ours to preserve and defend.”

She argued that blacks had a special responsibility to help ensure that the war’s primary goal was the liberation of darker peoples: “In this struggle for the ultimate good we must not confine its benefits only to Americans. We must abolish European, American and Asiatic imperialisms whose rivalry is basically the case of the present war. We Negroes who have suffered so long the evil effects of human greediness have a special obligation to make the white world aware of the human exploitation in seizing the lands and resources of others for material gain.”

Lane was generally silent in her column about the plight of Japanese Americans at the time of their mass removal, though she mentioned them in passing in January 1943 in championing The Militant, organ of the Socialist Workers party, and its stand against racial discrimination. “The Militant is charged with “stimulation of racial issues.’ This paper was started in 1928. [Are we to believe that] Up to that time Indians, Negroes, Japanese and Chinese were quite content with reservations, jim-crow laws, exclusion acts and the arrogance of white supremacy?”

Layne was more forthright in a March 1943 meeting in New York of the Civil Rights Defense Committee. There she referred to the placing of Japanese Americans in concentration camps as “a disgraceful blot” on the country’s record, and analyzed its economic ramifications. Lane pointed out that Japanese American teachers in the camps received a maximum salary of $19 per month, while white teachers performing the same work received $150 per month. “This is why I believe,“ she noted acidly, “that when it comes to the stimulation of race issues, the government is unquestionably the greatest offender.”

She also addressed in her column questions of discrimination against Asians. In May 1943, at the time of President Roosevelt’s meeting with British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, Lane urged them to grant India self-determination and end legal barriers against Chinese immigrants. She affirmed: “One word from you, Mr. President, and the Chinese Exclusion Act with all its prejudiced amendments, stigmatizing Orientals, will be reported out of the Committee of Naturalization and Immigration and passed by our Congress immediately.”

A month later, Lane devoted an entire column to denouncing the Supreme Court’s decisions upholding legal restrictions on Americans of Japanese ancestry:

[T]he June 21 decision of the court in the cases of Gordon Hirabayashi and Minoru Yasui—both American citizens of Japanese ancestry—indicate that the court not only heard its ‘Masters Voice’ but also under the impact of war justifies the disregard of the constitution and the practice of race discrimination. The decision…places the imprimatur of the Supreme Court upon the American-Japanese war as a race war.

Shortly after, the New York Times reported that the Socialist Party’s National Executive Committee, on which Lane joined Socialist leaders Norman Thomas and Maynard Krueger, had issued a report urging an investigation of the “growing evil of racism in America” and expressing specific regret over the Supreme Court’s Hirabayashi ruling, which it termed a ”sanctification” of the principle “of race differentiation and race discrimination.”

In February 1944, Lane deplored the bloodthirstiness of Christian groups who recommended bombing and destroying Shinto shrines in Japan to shatter popular beliefs in the protective power of the emperor. Lane objected that such calls would not only lead to pressure for more inhumane forms of warfare against Japan, but would trigger further discrimination against Japanese Americans, who were associated with the Japanese enemy in the public mind. Lane warned of an existing climate of hate in New York.

She remarked that a judge in a lawsuit brought by a Mr. Sakamoto had felt obliged to order jury members to take an oath to ensure full protection of his legal rights, while a police guard attended the ordination of a Japanese minister [Toru Matsumoto] to protect against hostile mobs. Worse, anti-Japanese forces on the West Coast were inciting “intolerant and vicious race prejudice” against Japanese Americans. Lane pronounced that “The bitterest witches’ brew since the days of Reconstruction is boiling on the Pacific Coast.”

In July 1944, Lane’s column again addressed the question of racism against Japanese Americans: “We Negroes live so constantly with our own problems that we are likely to forget that others have similar difficulties. The Pacific Citizen, the paper of the Japanese American Citizens League gives many incidents to show how vicious is race prejudice and how allied its manifestations are.” Lane noted a bill introduced in Canada by Secretary of State Norman Alexander McLarty to disenfranchise all citizens of Japanese ancestry. “[If] the McLarty bill is passed Japanese Canadians would be even worse off than our Negro brothers in the South.”

She concluded her column by underlining the larger importance of fighting racial discrimination against Japanese Americans, “Living in relocation centers, which are really concentration camps, our fellow citizens of Japanese ancestry are subjected to conditions which would strain the loyalty of the most ardent patriot…What happens to the Japanese in the United States is indicative not only of the strength of race prejudice here but also of the white race’s determination to maintain its position of dominance in the world. We Negroes should have no illusions about the kind of world we will face if that dominance prevails.”

Layle Lane retired from teaching in the 1950s, lived in Doylestown, then relocated to Cuernavaca, Mexico, where she died on February 2, 1976. After her death, the street that ran through La Citadelle was named Layle Lane in her honor. Although her collected papers are housed at the Schomburg Library in New York City, her career is little studied. Her commitment to freedom for people of all backgrounds deserves to be noted and celebrated.

© 2023 Greg Robinson