Donald K. Tamaki is intersectionality personified. As Senior Counsel at Minami Tamaki LLP, his lived experience and familial background give Tamaki unparalleled insight into civil rights issues. During a period in which there were hardly any Japanese American lawyers, he pursued the unpaved path and made his voice heard. He not only stands in solidarity with Japanese Americans, but with all disenfranchised groups.

Following the end of Japanese American incarceration in 1946, Tamaki was born in Oakland, California on May 26, 1951. Even though he was not incarcerated, he witnessed firsthand the impact that this experience had on his parents. He recalls that his family would just mention camp in the positive context, protecting him from what the harsh reality of camp was for them.

Tamaki attributes this to the “stain” on his father’s dignity, a very common mindset amongst the Nisei generation. He wouldn’t learn about the trauma and the economic losses experienced by his parents and other Japanese Americans arising from the mass removal until the 1981 hearings convened by the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians. Tamaki credits much of his development in his youth to this environment as well as the political climate at that time.

Growing Up Culturally Diverse

Tamaki grew up in a very ethnically diverse neighborhood in Oakland. The Tamaki family was a member of a Japanese Methodist church in the area, through which Tamaki was able to participate in many different co-curriculars including basketball and baseball. Tamaki also would go on to attend the public high school in the area, which was also very diverse. This diversity would lead Tamaki to participate in cultural exchange and making connections with his classmates.

Tamaki described his high school self as fun loving yet serious, which was very fitting for the time. He was going to high school during a very tumultuous period in American history. Tamaki recounts instances in which he was reminded that race mattered, including being asked, “No, where are you really from?” and getting into fights on December 7th every year due to someone blaming him for the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor.

Tamaki notes that at the time, Asian Americans were called “Orientals,” and at best were an invisible, subordinate population. At worst, they were regarded as second-class citizens, unequal and un-American. He stated that they began to challenge these perceptions and assert their rights as equal Americans as a result of consciousness-raising political events including the Black Civil Rights Movement, the Vietnam War, the assassination of Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., and the San Francisco State and UC Berkeley Third World strike for ethnic studies.

Tamaki, like many other students, was outraged with what he saw going on in the world and became motivated to change it. He became a student activist, co-led a citywide student organization called the Associated Student Union of Oakland, and organized a march on the Oakland School Board demanding ethnic studies curriculum and remedial programs to address educational disparities.

With respect to ethnic studies, students wanted to learn more about their own history, which had been erased. Don stated there was “nothing taught about the Japanese American Incarceration, nothing about Chinese Americans, except their role in building the railroad, and nothing about the discrimination and exploitation that they faced.”

Activist for Social Justice

Tamaki went on to continue his education at University of California, Berkeley during a time when the Vietnam War was escalating into a bloody conflict that divided the nation. At the time, Tamaki felt as though it was the right thing to speak out against the ongoing violence. He participated in numerous protests, speaking out against the war and other civil rights atrocities.

Tamaki even helped start a few organizations. These included Asian Health Services, which began as a student-led community health education program. It has evolved into a full service primary care provider with over 500 employees and serving over 50,000 patients.

Whilst protesting and community organizing, Tamaki took note of the community leaders, who were largely African American lawyers. He notes, “I modeled myself after black attorneys who were active in the Civil Rights Movement and who were leading demonstrations and risking their own physical lives and careers, professional careers, engaging in civil disobedience.” Tamaki wanted to embody similar passion within his own community and fight for social justice.

He continues, “Black lawyers fearlessly led sit-ins in downtown Oakland buildings that refused to lease commercial space to African Americans. And I thought, I want to be like them. And so that was one motivator for me to go to law school.”

Advocate for the Disenfranchised

Tamaki furthered his education at UC Berkeley School of Law, where he continued to be an advocate for disenfranchised communities. He jokes that he didn’t “fit the stereotype” due to his lack of proficiency in math or science, but he was always a gifted writer. He continued, “I could argue with a stop sign if I could,” which led to his natural fit in law.

He saw that attorneys, particularly African American attorneys, were able to serve as pillars of the community at a time where they needed to come together. Whilst in law school, Tamaki volunteered at the Asian Law Caucus, the first-in-the-nation public interest law practice co-founded by Dale Minami representing Asian Americans in civil rights and poverty law cases. Many cases arose out of San Francisco Chinatown, which had one of the highest concentrations of poverty in the city. As a law student volunteer, Tamaki wrote funding grants and was able to secure stable core funding necessary for the survival of the organization.

After Tamaki graduated from law school, he received a Reginald Heber Smith 3-year fellowship to do poverty law and civil rights cases. While the “Reggie” program was designed to recruit young lawyers to deliver badly needed legal representation to underserved communities, Tamaki recalled that a right-wing congressman referred to “Reggie” fellows as “the shock troops of the Left.”

Tamaki was placed in the San Jose area in the Legal Services Corporation office. There, Tamaki began working with the Asian American Law Students Association at the Santa Clara University Law School to found the Asian Law Alliance, which was modeled after the Asian Law Caucus in San Francisco. The mission of the Asian Law Alliance continues to be providing legal counseling, community education and community organizing. This institution has served thousands of first-generation immigrants, many of whom are very low-income and non-English speaking.

Case of a Lifetime

After his time with the Asian Law Alliance and work as a Reggie fellow ended, Tamaki was named the Executive Director of the Asian Law Caucus. There, Tamaki learned a different aspect of nonprofit work. He had always been an entrepreneur in a sense; working to lay the foundation for the future of the organization. As Executive Director, Tamaki spent much of his time on fund development to ensure the organization’s financial survival. But during his tenure, a case of a lifetime was brought to the organization.

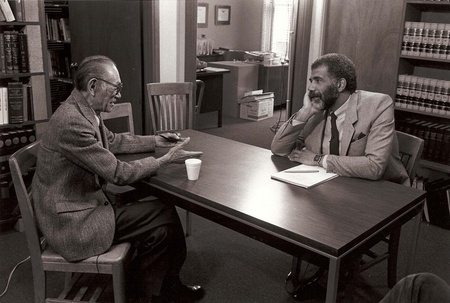

Dale Minami, who had departed the Asian Law Caucus to form his own private practice, was approached by Peter Irons, a lawyer, historian, and political science professor at the University of California, San Diego. Irons claimed he had discovered secret World War II government intelligence agency reports and Justice Department memoranda indicating that the government had lied to the U.S. Supreme Court in order to manipulate the outcome of the landmark 1944 decision Korematsu v. United States. After conferring with Professor Irons, Minami called Tamaki to see if the Asian Law Caucus was interested in becoming part of a legal team to reopen this case almost 40 years after the Supreme Court had issued its decision.

By way of background, Fred Korematsu, an American citizen born in Oakland, California, refused to obey the government orders forcibly removing Japanese Americans and incarcerating them in concentration camps. For his defiance, he was arrested and convicted. He appealed his case all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, and in 1944, the Court ruled against him.

It declared that in times of war, the government could suspend the rights of Japanese Americans and imprison them without charges, trial, and for no offense on the Army’s mere assertion that Japanese Americans were spying and therefore, locking them up was “military necessity.” For Japanese Americans, that meant being forcibly removed from their homes, unsure of when they would return and what they would return to. Over 120,000 Japanese Americans lost their homes, property businesses, family members, and dignity due to the forced removal.

The secret wartime documents that had surfaced were reports from the FBI, Naval Intelligence, and the FCC that categorically denied that Japanese Americans were spying. There were also Justice Department whistleblower memoranda admitting that the Army’s claims were “intentional falsehoods” and urging disclosure of this evidence to the Court. However, instead of disclosing this evidence, the Solicitor General suppressed the evidence and stood by the Army’s claims, knowing them to be false.

Tamaki stated that this case was personal, not just for himself but for all the legal team. Their families were put into these concentration camps. In Tamaki’s words, “There were no charges. There were no prosecutions. There was no opportunity to defend yourself. And so, they were simply rounded up because they happened to look like the enemy. So, this was, in essence, the trials that they should have had.”

© 2023 Drew Yamamura