On March 11, 2011, we all witnessed the triple disaster: human, material and nuclear that resulted from the Pacific region earthquake in the Tōhoku part of Japan with a magnitude of 9.1 on the Richter scale. Many of us witnessed, in real time, the devastation of the earthquake and tsunamis. It would not be an exaggeration to say that it was one of the most documented disasters due to the extensive digital telecommunications network that, despite its temporary collapse, allowed all users, with a mobile or cell phone, to record the events they witnessed. and broadcast them on your social networks.

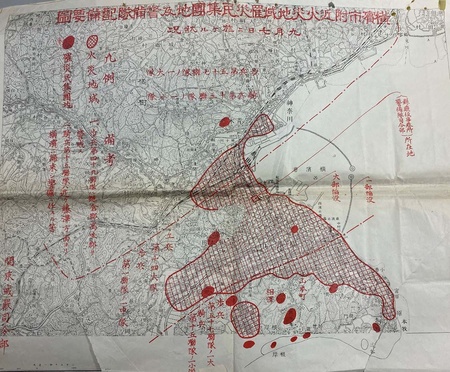

On a different scale, the Great Kantō Earthquake of September 1, 1923, which had an intensity of 8.2 on the Richter scale, generated (not only due to the earthquake and its aftershocks, but also due to the countless fires) a wave of destruction that devastated, mainly, Tokyo and Yokohama, as well as other nearby cities. Despite the damage to the infrastructure, the world was able to find out in great detail through the extensive news dispatches of The Associated Press (founded in the United States in 1846) reproduced by the world's newspapers.

Through this medium, readers were able to follow the depth of the damage from that conflagration and the number of estimated deaths just one day later. The above was complemented by the information (initially scarce) that could reach the Ministries or Secretariats of Foreign Affairs about the status of their diplomatic and consular representatives in Japan, or of the embassies or legations themselves located in that Asian country.

In Mexico, as in many Latin American countries, the information arrived immediately. The national newspapers filled their front pages with the colossal disaster that Japan was facing at that time. Shows of solidarity were presented through monetary contributions from governments, the organization of collections among the population and expressions of sympathy from people who went to the various diplomatic representations.

The government of Álvaro Obregón announced, in the written media, on September 8, 1923, the contribution of 50 thousand gold pesos and instructed the Secretary of Foreign Affairs, Aarón Sáenz, to consult with Minister Furuya Shigetsuma, accredited in the Mexican capital. , to indicate the means to send that contribution to Tokyo. The reaction was immediate from the Obregonista administration, but also from the expressions of Mexican society.

Various support campaigns were organized within the resident Japanese community. To mention one case, Jesús Minakata, a businessman from Jalisco and president of the Japanese Association in that state of the Republic, received the contributions.

These actions were replicated in other parts of the country. Various people who wanted to support the Japanese people in the face of this tragedy also contributed and went directly to the diplomatic offices of Japan in Mexico to deliver contributions whose total, according to information from the Japanese government, amounted to 2,326 pesos. 1 Likewise, it is noteworthy that the Japanese press, on September 15, 2 covered the news that Mexico was one of the nations that had supported Japan and by November 20, the financial support sent was already accounted for.

Regarding the great response of Mexicans to show solidarity with the tragedy that the Japanese people were experiencing, the newspaper El Democrat reported the following in a note:

“And in addition to this official aid, all our social classes have hastened to respond to the call that human fraternity is currently making to all well-born men; In recent days, there have been cases of people who have brought their sympathies and assistance to the legation.” 3

That is, there were two quantifiable channels of contribution: the government itself and through the various members of Mexican society. However, a third party can be added through the sending of money (today we call it remittances) that members of the Japanese community could have sent (by various means) to their relatives.

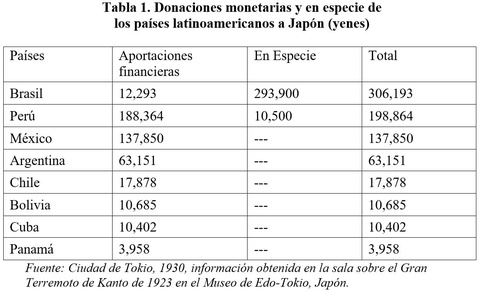

By 1930, the Tokyo government counted 137,850 yen total contributed by Mexico, being third after Peru, with 198,864 yen, and Brazil, with 306,193 yen. The interesting thing about the Brazilian case is that the contributions in kind (food and manufactured goods) were greater than the monetary resources sent. On the other hand, in Peru the process was reversed, since their financial aid was greater than the in-kind contributions. It is interesting that the newspapers reported that Colombia 4 had sent wood, but in the official data they were not counted, unlike the contributions from other countries such as Argentina, Chile (9,230 yen, donated by the Association of Saltpeter Producers), Bolivia, Cuba and Panama. (See Table 1).

It is still an open topic of research to know the number of deaths of Latin Americans (including naturalized issei or nissei ) during the Great Kanto Earthquake. In very recent investigations, we found the fact that three members of a Mexican family, perhaps the only one at that time not counting that of the members of the Mexican foreign service accredited in Japan, died.

They were: María Soledad Enrique, María Rosa Enrique and María Luisa Enrique, whose father, Joaquín Roberto Guadalupe Enrique Cerecero, had been consul in Yokohama and after the end of his diplomatic responsibility, obtained a contract in a foreign trade office. The tragedy of the Enrique family was unknown for many years.

In general, the frequent displays of sympathy from Mexican society generated widespread gratitude from Japan. Minister Furuya expressed it with the following statement published in the Mexican press:

“The Japanese government has sent telegraphic instructions to this legation, in the sense that the Japanese and Mexican people be made aware of the deep gratitude of His Majesty the Emperor... on the occasion of the sympathy and help received... on the occasion of the earthquakes that occurred last September… a resolution was taken by each of the aforementioned chambers in the sense of expressing deep gratitude to Mexico and other foreign nations.” 5

After formalizing bilateral diplomatic relations between Mexico and Japan in 1888, in the face of a regrettable and tragic event like that experienced in Japan in 1923, the immediate response of the government, and in particular of the Mexican people, was the first show of broad sympathy towards Japan. in dramatic moments after the wave of destruction derived from the earthquake that devastated the Kantō region.

Although Japan was visible as an emerging actor in the Pacific and the Mexican newspapers reproduced various news about friction with the United States, issues about Japanese politics and culture, or even coexistence with members of the Japanese community, one could learn about its traditions and way of life; The immediate and massive information from the news agencies about the Great Earthquake undoubtedly expanded their knowledge about Japan in all segments of Mexican society.

The gratitude of the Japanese government also resulted in the decoration to the Mexican president, Álvaro Obregón, which was received on November 23, 1924. Likewise, a couple of months before, through Minister Furuya, he notified Foreign Minister Aarón Sáez that the The Japanese community living in the country had decided to suspend the claims process for material damage caused to their properties during different moments of the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920).

It is also relevant to add that within the framework of the Treaty of Commerce and Navigation signed on October 8, 1924 between the two countries, Article XXV included the resignation of both governments in the event of any claim by their citizens due to any insurrection or civil war.

Likewise, the diplomat pointed out that Tokyo supported this initiative, indicating that it had been instructed to persuade Japanese residents who have not done so to renounce their pending claims. The reasons given focused on the cordiality shown by Mexican society to residents of Japanese origin throughout the national territory and, in particular, the support shown towards the Japanese people during the 1923 earthquake. 6

100 years after the Great Kanto Earthquake of 1923, it can be considered to have been the precedent for the constant and frequent expressions of support that have existed between Japan and Latin America in the face of natural disasters. In the particular case of Mexico, in the earthquakes of September 19, 1985 and 2017, adding also the examples of Latin American solidarity in the aforementioned earthquake in Tōhoku in 2011. That is, a link, little documented, was forged between the ties of friendship existing today and in the future.

Grades:

1. “各国義金”, 『国民新聞』 November 20, 1923.

2. “全世界が延 べた救ひの手”, 『神戸又新日報』 September 15, 1923.

3. “For 6 days Japan has…”, El Democrat , September 8, 1923, p.7.

4. “既に二百万円 : 紐育だけで集まった”, 『大阪朝日新聞』 September 8, 1923

5. “The Japanese cameras express their gratitude to the Mexican people,” El Mundo , December 18, 1923, p. 1.

6. “Communication from Minister Shigetsuma Furuya to the Secretary of Foreign Affairs, Aarón Sáez”, September 3, 1924, Historical Archive of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan.

© 2023 Carlos Uscanga