Tsunezō Wachi 1 (和智恒蔵) was born on July 24, 1900 and graduated from the Naval Academy in 1922, simultaneously studying Spanish at the Tokyo University of Foreign Studies where he also learned English. He was assigned to the Army Cavalry Regiment and in 1932 he entered the Imperial Navy Communications School in Yokosuka, where he specialized in the area of radio transmissions and cryptography.

Upon completing his academic training, Wachi was assigned to the communications area of the ship Naka . Between 1935 and 1937 he was a member of the Military and Naval Intelligence Division, in which he was assigned to go to Shanghai to intercept British communications, as well as – through other Japanese agents – to spy on high-ranking officers of the British Army to photograph their code books.

After his return from China, Wachi was sent to the Owada Radio Communication Station, located in Saitama Prefecture. The following year, he was transferred to a training ship to be an instructor and responsible for the radiocommunication area, and later, he was appointed by the Ministry of the Navy to be responsible for the radio-intelligence area against the United States in which he monitored the movements of the American fleet in the Pacific.

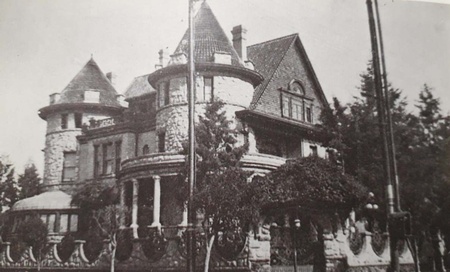

In November 1940, he was appointed assistant to the naval attaché of the Japanese Legation in Mexico, for this purpose he embarked on the Hie Maru heading to the port of Manzanillo, Colima. At that time he was the object of interest by the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) for discreet surveillance due to his status as a diplomat.

Wachi arrived in San Francisco on December 9, on a short stopover, and it is reported that during his stay he met with an employee of the Yamato Hotel, to whom he gave two packages and an envelope; The same one who was well known to the intelligence services, since many Japanese soldiers and sailors contacted him upon his arrival in the United States, so he was under constant surveillance.

After his arrival in Mexico City, Wachi had two very particular assignments. On the one hand, assist his boss Kyoho Hamanaka (浜中匡甫), naval attaché of the Legation, in his socialization tasks with Mexican soldiers. According to him, there was great competition with their counterparts at the American embassy to gain relevant information through social gatherings where alcohol and food had no limits.

On the other hand, he was responsible for the actions of intercepting communications and decoding them to know the movements of the American fleet in the Atlantic and, in particular, he had been asked in Tokyo to know in detail the scope of the “support fleet” that operated. in the transatlantic zone, which turned out to be a group of ships for the protection and surveillance of other ships.

As part of the actions undertaken to communicate to the Japanese government the information obtained through the interception of messages and that provided by Mexican officials, Wachi sent his reports in invisible ink by postal mail to Argentina, where they were retransmitted to Tokyo. . In the same way, it used secret German radio transmission stations located in different parts of the Mexican Republic, to later be sent to Japan.

Wachi's intelligence activities also included knowing the movement of the United States fleet through the Panama Canal, which were later corroborated by the interception of messages made by Wachi and his team. Likewise, he refers to the fact that Colonel Yoshiaki Nishi (西義章), the military attaché, had a friend who was already retired from the US army and provided him with various information about the number considered for the deployment of troops in Europe and Australia, the plans for the establishment of a military base in Brazil, the establishment of production and supply of military supplies in China and Washington's plans for the construction of more submarines.

Although there was no shortwave transmission equipment in the legation, there were, according to Wachi, several reception devices where they could clearly capture the messages from the ships to the naval stations located on the coast. According to the diplomat, the altitude of Mexico City favored the interception of these communications.

An interesting aspect that Wachi refers to was the use of Mexicans to help in intelligence work. He refers to the fact that he made a friend in a cabaret who was a student and who worked in a tourism agency, and he paid him to go, with his girlfriend, to San Francisco, and report the number and location of ships in the bay. . For that service - apart from paying for his trip - that person received 3 thousand pesos, even though he did not trust his information or his person much.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, and the breaking of diplomatic relations with Japan, Wachi along with the Legation staff were confined in the diplomatic representation under surveillance by the Mexican authorities and the FBI. When his departure from the country was confirmed, in February 1942, Wachi decided to get rid of the radio communications and encryption equipment, for which, he says, he threw most of it into a well located on the Legation grounds and one of them was lost. He was buried in the Cuajimalpa area, in Mexico City. However, it was seen by local residents and the incident was reported. The press followed the news and, later, he was required to testify before the public prosecutor's office about this fact; however, since no crime was proven, he was released.

After his repatriation as part of the prisoner of war exchange program, and his confinement with other members of the Japanese Legation in the United States, he was finally able to board the Gripsholm , which had been rented by the State Department for the repatriation. and exchange of prisoners, citizens and diplomats of the Axis powers in August 1942, bound for Lorenzo Marques, in Mozambique, where they would board the Asama Maru . Arriving in Singapore, he took a plane to return to Japan that way.

After his arrival in Tokyo, Wachi was appointed head of the radio intelligence unit at the Ministry of the Navy, and was later transferred to Iwo Jima Island as garrison commander, where he commanded more than 1,300 sailors. The Japanese knew the strategic value of the island and Tokyo began fortifications and the construction of three landing strips, as well as the construction of long-range radio antennas.

Some time later, Wachi was sent to the Philippines as a naval attaché and later as commander of the 32nd assault section, located in Kagoshima, which was destined to carry out preparations for a hypothetical North American invasion of the Japanese archipelago. Wachi points out that they carried out exercises with small submarines, torpedoing practices, including human torpedoes. In that city he was detained by the Allied Forces when Japan signed its surrender on August 15, 1945.

On July 29, 1946, he entered Sugamo prison as a prisoner of war, where he was interrogated by the intelligence services of the SCAP (Supreme Commander for Allied Powers). His defense managed to prevent him from being tried in the International Military Tribunal of the Far East and he was released on October 4, 1946.

Wachi made a radical change in his life by becoming a Buddhist monk of the Tendai sect, changing his name to Tsuneami Jushoan (寿松庵恒阿弥). Indeed, after obtaining his religious training in Kyoto, Wachi joined the White Lotus Society, which was a Buddhist organization, founded in 1948 by Kazumasa Onishi (大西和正), with the initial objective of carrying out donation and charity activities. to needy groups and seek the rejuvenation of Buddhism in the Post-War context. The CIA monitored the activities of the Society, which increasingly included former members of the army and navy; and paid attention to the increasingly important role that Wachi assumed in it.

In that sense, the Buddhist organization added to its activities, already with Wachi, providing spiritual guidance to the prisoners of the Japanese navy and army who were confined in the Sugamo prison. Likewise, its activity was aimed at commemorating the Japanese fallen on Iwo Jima, by requesting the American authorities to return the skulls of the bodies of the Japanese combatants that had been extracted from the island; as well as spiritually assist and help comfort the families of the soldiers who lost their lives.

This activity placed him again as a person of interest to the CIA and different reports were made in particular when he obtained authorization from SCAP to go to Iwo Jima to collect the remains of his war companions and return them to Japan offering religious services, in addition to honor them with the placement of a memorial. Contrary to what one might think, Wachi found a quick response to his requests from the US authorities. Perhaps an element to consider is that, according to him, he instructed US personnel in the area of interception and decoding of messages coming from the Soviet Union, which could have been a negotiating factor with SCAP officials.

In addition, Wachi achieved media attention and fame by raising the issue of Iwo Jima, even renting a charter plane to go to the island carrying three journalists. Media notoriety was not diminished by the scandal in which Wachi and Onishi had been involved with the resale of used clothing donated by other Buddhist organizations in the United States to Japan. In the 1953 elections, he participated as a candidate in the Progressive Party, championing the issues of the complete rearmament of Japan for defensive purposes, he advocated implementing a pension for war veterans and for the families of fallen soldiers and sailors, the return of Okinawa, as well as the release of prisoners of war. However, he only obtained 18 thousand votes, which were insufficient to win a seat in the Japanese Diet.

Despite losing his election, he continued with the Iwo Jima issue by founding an association of which he was its first president and member until his death on February 2, 1990 at age 90. A couple of years later, the writer Fukuyo Ueaka ( 上坂冬子) wrote the book Iwo Jima Has Not Yet Been Crushed (硫黄島いまだ玉砕せず), in which he recounts Wachi's experience on the island and his subsequent activity for the recovery of the remains of Japanese soldiers.

Thus ends the unusual life story of Tsunezō Wachi who, from being a faithful member of the Imperial Navy in charge of intercepting and decoding messages from the Allied Forces transmitted by radio in the prelude to the Pacific War, turned his life into embrace Buddhism and become a monk who dedicated the rest of his life to commemorating his fallen comrades-in-arms on Iwo Jima.

Note:

1. The order is first name and last name, however in Chinese characters it is last name and first name.

© 2021 Carlos Uscanga