When a collections representative for Pacific Gas and Electric sent out a regular utility bill to Mr. Yoshiyuki Akiyama of San Francisco in late January 1942, the company received no reply. Mr. Akiyama, a former resident of Apartment 5 of 1920 Pine St., San Francisco, was unable to respond. Earlier that month, he was taken by the FBI and sent to the Fort Missoula internment camp in Montana, arriving at the camp on January 30, 1942.

In the months leading up to December 7, 1941, Japanese nationals like Akiyama—along with German and Italian nationals—were documented and added to a national registry. Immediately after the bombing of Pearl Harbor, the Department of Justice conducted mass arrests of enemy aliens based on these lists and sent them to a series of internment camps across the U.S. For Japanese nationals—who were barred from becoming U.S. citizens due to immigration laws—such arrests targeted first-generation Japanese immigrants (Issei) and devastated the wider community, stripping households of fathers and husbands, and communities of teachers and community leaders.

Akiyama and hundreds of other Issei from San Francisco were then sent by train to Fort Missoula Internment Camp in Montana. Conditions in camp were bearable enough to face the bitter Montana winters, but nonetheless painful. For internees like Akiyama, their future depended on hearings with Department of Justice officials that decided if they could join their families in newly built War Relocation Authority camps, or face further detention and deportation. While living on meager rations and facing below zero temperatures, internees like Akiyama had enough to worry about with their own and their family’s safety, let alone paying the monthly utility bill for their apartment.

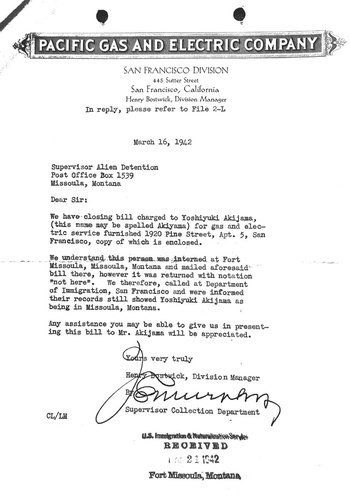

However, PG&E went out of their way to find Akiyama. At first, PG&E wrote to the camp officials inquiring about his whereabouts. When the commandant responded that he wasn’t there, the collection’s officer called the Department of Immigration’s San Francisco office and confirmed that Akiyama was, in fact, at Fort Missoula. A second letter arrived on March 16, 1942 to Fort Missoula requesting the commandant to deliver the bill to Akiyama.

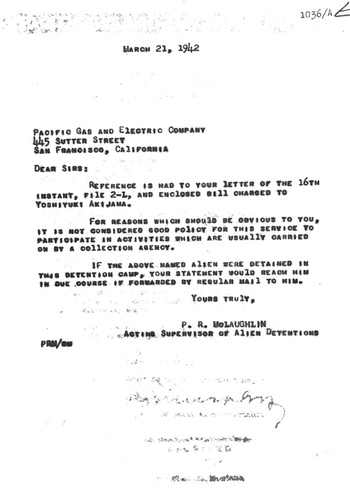

The camp authorities were so stunned by the company’s persistence that they wrote in their response: “for reasons which should be obvious to you, it is not considered good policy for this service to participate in activities which are usually carried on by a collection agency.” While the letters stopped, the company’s persistence is telling. At a moment when many individuals faced dire times in internment camps, PG&E insisted on collecting on a utility bill and have the government use its power to extort an individual like Akiyama.

Although the callousness of PG&E’s decision to write to Fort Missoula in 1942 seems farfetched, it was not the only case. Whether as active supporters or as concerned parties fearful of losing workers and customers, corporations on the West Coast were affected by the incarceration of Japanese Americans in 1942. In the case of PG&E, the forced removal of Japanese Americans presented a number of dilemmas and opportunities to the company.

After December 7, PG&E facilities such as powerplants, water supplies, and gas lines were cited by the War Department and Department of Justices as strategic areas and potential sites of sabotage that legitimized forced removal. As Northern California’s primary utility company, PG&E suddenly found itself without thousands of customers as they were sent away to ten concentration camps or INS internment camps across the United States.

Initially, PG&E presented itself as supportive of Japanese Americans. Before forced removal in early 1942, Robert R. Gros, PG&E’s public relations representative, served on a nonprofit committee that supported voluntary resettlement of Japanese Americans. The non-profit group, which included Galen Fisher of the Institute of Pacific Relations, initially proposed in February 1942 that Japanese Americans leave the West Coast for farm cooperatives instead of camps. When forced removal was ordered by the Army’s Western Defense Command in March 1942, the group was dissolved.

Nonetheless, business went on as usual despite the ongoing tragedy. For Japanese American unable to sell their homes or businesses during the last-minute fire sales before removal, paying utility bills did arise. In some cases, friendly neighbors agreed to cover the expense. When the Takagi family was sent to Tule Lake, they left behind the Takamum Nursery in Mountain View. J. Elmer Morrish, the Vice President of the First National Bank of Redwood City, agreed to cover the Takagis’ utility bills for the family business during their incarceration. Morrish became known for his help of other Japanese American families throughout San Mateo county, a story documented in Linda Ivey and Kevin Kaatz’s book Citizen Internees.

But for most Japanese American families who did not have outside support, unattended houses and businesses led to accumulated bills, leading to collections cases like Yoshiyuki Akiyama. The incarceration made the war years a harrowing experience for Japanese Americans, and the incoming bills from houses and businesses left behind reminded the confined of the outside world, in negative ways. It also stirred new anxieties of what would happen to their abandoned houses. News reports of vandalism and theft occurring on the former properties of Japanese Americans, and eager debt collectors willing to prey on Japanese Americans in camp left many with a sense of uncertainty.

Mr. Akiyama’s PG&E bill tells two stories—one of corporate interactions with the camps, the other of intervention of the outside world into the lives of confined Japanese Americans. It also reminds us of the financial precarity Japanese Americans lived with during and after the war. The Federal Reserve froze the bank accounts of all Issei immediately after Pearl Harbor, with the restriction later relaxed to monthly withdrawals of $100 thanks to lobbying by Eleanor Roosevelt, yet bills trickled in uninterrupted. Mr. Akiyama’s bill tells a greater story of not just corporate insensitivity towards confined Japanese Americans, but also how life for Japanese Americans was thrown into chaos as a result of their incarceration.

© 2020 Jonathan van Harmelen