From November 1, 2023 to February 25, 2024, the Shiga Peace Museum in Higashiomi City, Shiga Prefecture, hosted Broken Promises: Japanese Canadians in the Pacific War, an exhibition on the wartime displacement and dispossession of Japanese Canadians. This exhibition, which was originally created by the Nikkei National Museum in Vancouver and toured across Canada, not only linked Nikkei studies in Canada with migration studies in Japan, but also created new connections among the communities within Japan where the migrants in Canada originated.

A Historic Day for Japanese Canadian Migration Studies

November 18, 2023 became a historic day for the study of Japanese migration to Canada. The largest number of Japanese migrants to Canada in the prewar period came from Shiga Prefecture, followed by Wakayama Prefecture. On this day, local study groups in former emigrant villages of these two prefectures gathered at the Shiga Peace Museum.

This exchange was made possible by the travel exhibition, Broken Promises: Japanese Canadians in the Pacific War. Broken Promises was an exhibition of the Nikkei National Museum in Canada, launched in 2020, on the wartime displacement and dispossession of Japanese Canadians. Japanese Canadians living on the west coast were forcibly relocated out of the area extending 100 miles inland from the coast. Not only that, the Canadian government sold off all of the property they had left behind on the west coast without their consent. It then sent a small cheque to the owners for the proceeds after subtracting the cost of the relocation it had forced on them as well as the costs of their living in the camps. This policy caused Japanese Canadians to lose all of the property they had worked so hard for decades to build.

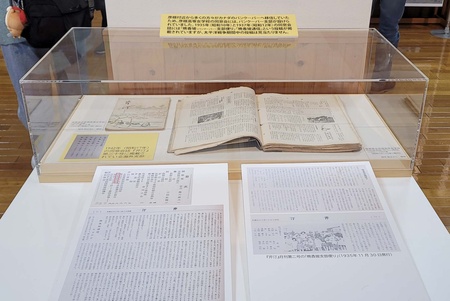

The Broken Promises exhibition tells the stories of seven of these families, providing information about their pre-war lives, their experiences of displacement and incarceration, the government’s policy-making process in deciding to sell off their property, letters from the exiled Japanese Canadians to the government protesting the sale of their property, and the inter-generational impacts this racist policy left on their families. The Nikkei National Museum in Canada created this exhibition based on the research findings of “Landscapes of Injustice,” a Canadian joint research project on Japanese Canadian dispossession.

For the traveling exhibition in Japan (Executive Committee: Masumi Izumi, Norifumi Kawahara, and Sachiko Kawakami), the Japanese research team replaced the French explanations in the original bilingual exhibits with Japanese explanations. The Japanese curators and immigrants’ descendants added materials and information from Shiga and Wakayama to localize the exhibition in order to enhance the Japanese visitors’ interest.

The traveling exhibition started at the Shiga Peace Museum (November 1, 2023-February 25, 2024). It will next go to the Canada Museum in Mio, Mihama-cho, Wakayama (April 1-June 30, 2024), the Doshisha Gallery, Harris Museum of Science and Chemistry, Doshisha University in Kyoto (late November to late December, 2024), and the JICA Museum of Overseas Migration in Yokohama (2025, date to be determined).

The fact that many Shiga Prefecture residents emigrated and worked in Canada before World War II is not commonly known even within the prefecture. It is quite significant that this exhibition is helping to spread the knowledge about the deep and close connections between Shiga and the rest of the world. Wakayama Prefecture has actively promoted its history as an emigrant prefecture over the past several years through a variety of projects. In particular, the Mio district, also known as “Amerika Mura (America Village),” is working to revitalize itself by bringing its history as an emigrant village to the forefront. The village sent so many villagers to Steveston, a fishing town south of Vancouver, that it is no exaggeration to say that Mio and Steveston were “one village extending across the Pacific Ocean.”

The staff of Mio’s Canada Museum, together with junior and senior high school students and their teachers in “Kataribe Junior” (a group studying local history in Mio), visited Shiga to meet for the first time with descendants of Japanese Canadians there. Also on this day, a local research group that studies the Iso district of Maibara City, and a local historian from Kaideima, Hikone (both of which are major emigration villages in Shiga), met for the first time. They exchanged information about their ancestors and efforts to uncover their local emigration histories.

Memories of the Pacific War Slowed Down the Evolution of Historical Research on Japanese Emigration

To help readers understand the significance of this exchange, I would like to explain a little more about the current state of Japanese overseas migration studies in relation to the memories of the Pacific War in Japan and North America. The venue for this event, the Shiga Peace Museum, is a prefectural museum that opened in 2012 to preserve and pass on war-related materials and memories to the next generation in the prefecture.

The idea for the museum came about nearly three decades earlier (around 1984), and efforts to collect materials and information from war survivors began in 1993. The youngest people who experienced the Pacific War were already over 50 years old then and are over 80 in 2024. The materials and memories gathered and heard over the past 30 years are extremely valuable in preserving the facts related to the war for future generations. The Shiga Peace Museum plays an important role in preserving these materials and sharing them with visitors through permanent exhibitions, special exhibitions, and peace education lectures and classes.

Preserving memories and artifacts related to Japanese overseas migration is also a race against time. The history of Japanese emigration is marked by the period from the 1880s, when a full-scale migration to Hawaii began, to the end of the Pacific War. Although the postwar Japanese government promoted emigration efforts to Brazil and the Dominican Republic, etc., the number of emigrants decreased as Japan’s economy grew. Many Japanese were subsequently sent by companies and other organizations to work overseas, but they rarely identified themselves as immigrants, and only a few renounced their Japanese citizenship or acquired the citizenship of the countries to which they were dispatched.

Furthermore, the overwhelming majority of Japanese overseas were those who lived in the colonies such as Manchuria, Korea, and Taiwan, and their experiences are inseparable from Japan’s memory of defeat in the Pacific War. This led to the erasure of emigration history from the collective memory of the Japanese people in the postwar period. Thus, a situation developed that made it difficult for the former emigrants to talk about their experiences and for the next generation of returnees to take an interest in their transnational roots. Only recently is this trauma being resolved.

On the other hand, Japanese immigrants and their descendants living in Canada, the U.S., and other areas that became Japan’s enemy nations experienced wartime relocation, incarceration, internment, and dispossession. Through this experience, the Nikkei communities lived through the postwar period with the trauma they felt from “being Japanese.” Japanese Americans and Japanese Canadians strived to integrate into mainstream society as Americans and Canadians, and in the process, many lost their connection to the Japanese language, Japanese culture, and the land of their ancestors.

In recent decades, ethnic diversity has become linked to cultural richness in Canada and the United States. Genealogy and roots tourism, in which people trace their ancestral cross-border histories, are becoming increasingly popular. Now every year, larger numbers of the Nikkei wish to visit their ancestral lands.

Research conducted in Japan on overseas migrants did not become established as “migration studies” until the 1990s, and it was not until the 21st century that the interest in Japanese emigrants and their descendants expanded beyond academia into the general public. The field of ethnic studies, which has developed significantly in North America since the 1970s, has long focused on the integration of immigrants into mainstream society, and research that takes into account the situation in the immigrants’ countries of origin did not come until the “transnational turn,” which took place in the 1990s.

In the studies on Japanese immigrants, it is only recently that immigration and ethnic studies in Canada and the U.S. were linked with emigration studies in Japan. Nowadays, the surviving former emigrants, like war survivors, are rapidly aging, so finding and preserving emigration-related materials and interviewing those survivors is becoming more difficult with each passing year. In light of these trends in immigration history, this traveling exhibition is a historic moment that has not only linked Canadian and Japanese research, but also established a link between people from the former emigration centers in Japan.

Part 2 will describe the presentations given during the public lectures at the Shiga Peace Museum in conjunction with the Broken Promises exhibition.

© 2024 Masumi Izumi