>> Part 1

As in Japan, taiko’s function in the United States took a dramatic turn once it was taken out of a ritualistic context. Putting the drum away after the Bon odori in the summer of 1969, Reverend Masao Kodani of Senshin Buddhist Temple in Los Angeles and a temple member George Abe started playing the drum. Hours later, with blistered and bloodied hands, the two young Nikkei men decided that “it was fun!” They were soon joined by other sansei who were looking for activities that allowed them to express both their heritage and cultural hybridity. They formed Kinnara Taiko, and it became the first taiko group formed for Japanese Americans by Japanese Americans.

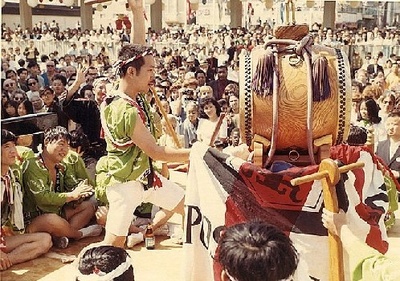

San Francisco Taiko Dojo, the first kumi daiko group in the United States, was founded by Seiichi Tanaka in 1968. Gift of San Francisco Taiko Dojo (2005.97.2). Japanese American National Museum.

A year earlier in 1968, Seiichi Tanaka, a postwar immigrant from Japan, had started performing taiko in local Japanese community festivals in San Francisco. Tanaka studied with Osuwa Taiko and O Edo Sukeroku Taiko, and his important contribution to American taiko history is that he brought drumming techniques and forms from Japan to the United States. He started teaching taiko in San Francisco, eventually forming San Francisco Taiko Dojo. Taiko Dojo’s stoic teaching style was similar to Japanese martial arts training that emphasized discipline and physical/mental strength, while Kinnara’s laid-back and egalitarian approach was based on Reverend Kodani’s philosophy that taiko could be used for Buddhist training and as a means to help individuals overcome their ego. These two groups pioneered the two contrastive approaches to taiko in North America.

The third group, San Jose Taiko, which was organized in 1973, combined these two different ideologies and developed its own style of taiko, both as a performing art and as an organization. San Jose Taiko pursued rhythmic and visual aesthetics and at the same time insisted on maintaining egalitarian and democratic organizational principles, which its principal members, Roy and PJ Hirabayashi, considered essential in order to preserve taiko’s original tie with Japanese American community activism.

The three pioneering taiko groups, San Francisco Taiko Dojo, Kinnara Taiko and San Jose Taiko, inspired many Japanese American community activists, because taiko was a loud and powerful tool of self-expression for Japanese Americans, who had been stereotypically considered to be quiet, submissive, and well assimilated into the mainstream American society and culture. Community activists formed taiko groups in New York, Denver, Mt. Shasta, Seattle, Vancouver, and many other North American cities. As a tool of self-expression, Japanese American taiko developed its own style, rhythms and songs that were distinctively different from the taiko tradition in Japan. Reflecting their multicultural musical environment, American groups utilize rhythms that tend to be more jazzy and syncopated. Additionally, they seem to place more attention on rhythm patterns and visual aesthetics, in contrast to Japanese taiko groups who tend to emphasize the purity of the sound.

Initially Japanese Americans started taiko as a cultural movement to claim a positive and powerful image of their cultural heritage at a time when ethnic and racial minorities in the United States engaged themselves in civil rights and ethnic power movements. In recent years, however, taiko has become a popular cultural activity among Americans of both Japanese and non-Japanese heritage. There are over two hundred taiko groups in the United States, and although a majority of them are still run by Japanese American or Japanese members, there are groups that have no Japanese or Asian members in the group. There are taiko groups in Canada and Latin America—places in the world where Japanese immigrant communities exist. There are also taiko groups in countries without a large number of Japanese immigrants, such as Russia, Germany, and the United Kingdom.

We do not yet know whether or not taiko will become the next Judo, Karate, and Aikido—Japanese cultural forms whose popularity has expanded so much beyond Japanese ethnic boundaries that the majority of practitioners and students have no connection with Japan or Japanese communities abroad. Neither do we know how taiko will change if this happens. Will taiko become one of the many percussion instruments played with any style of music? Will the taiko community create a global standard to police the boundaries of the definition of taiko as in Judo? Will taiko develop into various local styles of music as it migrates to different parts of the world, as has happened with African forms of drumming?

Historically, taiko has met various human needs—religious, recreational, artistic and political. It has engaged people on physical and spiritual levels. Nowadays, taiko provides a means through which some people may explore their curiosity for “exotic” cultural art and philosophy. This may explain in part the rapid increase of taiko drummers and fans in non-ethnic-Japanese communities. In any case, the power of taiko—and its profound sound and deep vibration that goes straight to the kokoro (heart) and hara (guts)—no doubt has a universal appeal, especially at this time in human history when people in the world are becoming increasingly open to different cultural traditions.

© 2006 Masumi Izumi