“Anti-Chinese sentiment is on the rise yet again, especially since 2020 with the COVID-19 pandemic, and with it a dramatic increase in anti-Asian violence. Fanned by anti-China sentiment, animosity and blame extended into a pan-East Asian discrimination that targeted vulnerable people, especially lower-income seniors and women, which in turn became its own epidemic. If there was ever any doubt about whether events in the past impact our current lives, this is yet more proof.”

— Author Henry Tsang (1964- ), White Riot: The 1907 Anti-Asian Riots in Vancouver (2023)

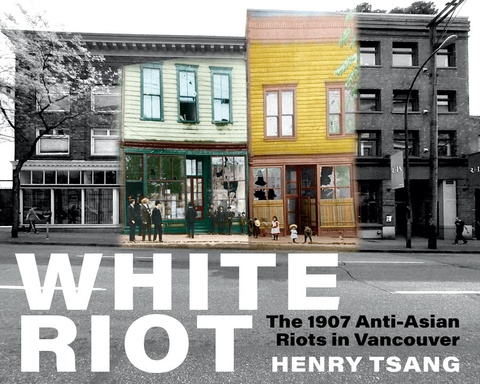

Henry Tsang’s new work, White Riot: The 1907 Anti-Asian Riots in Vancouver, puts the spotlight on one of the first anti-Asian riots in Canada: the three-day riot in the city’s Powell Street/Japantown and Chinatown districts.

Henry Tsang—a visual and media artist, associate professor at Emily Carr University of Art + Design in Vancouver, and author—launched the 360 Riot Walk, a 360-degree-video walking tour that traced the route of the riot as part of the 2019 Powell Street Festival in Vancouver, BC, just prior to the Covid pandemic. The tour takes participants through Vancouver’s old Japantown (Paueru Gai) and Chinatown area, following the route that was taken by the mauradering white mob that attacked Chinese and Japanese businesses from September 7th-9th, 1907.

Tsang has been critically examining Asian Canadian identity and history for some time mostly through art including his 2021 Hastings Park: a series of colour photographs and infrared projections depicting the four remaining buildings in Hastings Park at Vancouver’s Pacific National Exhibition where more than 8000 Japanese Canadians were imprisoned before being sent off to labour and concentration/prison camps. He’s also worked with Vancouver’s Chinese Cultural Centre and at artist-run centres to produce curatorial projects such as Self Not Whole; Cultural Identity and Chinese Canadian Artists in Vancouver (1991) and City At The End of Time: Hong Kong 1997 (1997), among others.

Revisiting 1907, is an important reminder of Canada’s own anti-Asian narrative, certainly ongoing since the first recorded JC immigrant, Manzo Nakano, arrived in Victoria, BC in 1877.

The in-person guided tours are not exclusive to the Powell Street Festival, as they organize tours before, during, and after the festival from July to September, follows the same route as the rioters would have taken. Otherwise, it’s available online on any web browser via the site 360riotwalk.ca. The tour pauses at 13 locations, beginning at Maple Tree Square, Gastown and includes Shanghai Alley (Chinatown Heritage Alley), across from 122 Powell Street; passing by “Fish Market Grocery T.S. Maikawa” at 264 Powell Street; 374 Powell Street (Tamura Building AKA New World Hotel), designed by Shinkichi Tamura who arrived in Vancouver in 1889; the Japanese Language School; concluding at Powell Street Grounds (Oppenheimer Park).

One of the challenges of presenting the 1907 riot in this manner is that, yes, it is a “walking tour” that is really best experienced by being there. Describing 360 video technology, Tsang says, “Editing plays a key role in shifting perspectives or location or time. VR is most commonly experienced with 360 headsets and handheld controllers.”

Tsang’s 360 Riot Walk as a “documentary, a mapping project, and an artwork” sets the context of the riot by incorporating historical pictures like a cover illustration of an 1879 Canadian Illustrated News depicting “The Heathen Chinee in British Columbia;” an 1877 illustration “The First Blow At The Chinese Question” from San Francisco’s Illustrated WASP; The Vancouver Daily Province newspaper September 9, 1907 headline “Chinese Buy Revolvers For Defence In Case of Riots;” colourization of the archival images like White Canada: Men of Canada; and a picture of Vancouver’s first city Council meeting after the Great Fire of 1886, Shanghai Alley after riots and a RIOT FOOD HERE menu perspective (including Daal and Chapati) inspired by 1907. Also included is the script for the walking tour which Tsang co-wrote with Michael Barnholden.

Tsang reminds readers about the chronology that led up to the riots. In 1882, the US banned Chinese immigration; Canada imposed a head tax of $50 on Chinese in 1885, increasing it to $500 in 1903. Vancouver’s first anti-Chinese riot was in 1887. It began at a Coal Harbour encampment and continued to Chinatown where homes were looted and buildings set on fire. After Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905), about 2000 Japanese immigrants arrived in Canada in 1905-1906.

Anti-Asian racism swept up from San Francisco where in 1905 the segregation of a small number of Japanese students resulted in whites boycotting Japanese-owned restaurants. There was a riot against Japanese businesses, fomented by the Asiatic Exclusion League and the local press. In August 1905, there was an attack on Japanese cannery workers in Blaine, WA.

On September 5, 1907, in Bellingham, WA, there was a race riot where 500 Punjabi sawmill workers were attacked by white workers and marched out of town. They headed to Canada where they were allowed to enter because they were British subjects, arriving just in time to witness the Anti-Asiatic Riot in Vancouver that was fomented by the Asiatic Exclusion League.

In 1907, Vancouver mayor, Alexander Bethune (1852–1947), asked the federal government for permission for use of the Kitsilano Indian Reserve, land that is still unceded today. It was also an area that had a thriving Japanese Canadian community prior to 1942. Today, Kitsilano is one of the city’s most ‘exclusive’ neighbourhoods.

The city of Vancouver was booming, experiencing a population explosion from 21,000 in 1901 to 70,000 in 1907. Also, in that same year, the Grand Trunk and Pacific Railway lobbied the federal government to import 10,000 Japanese workers to build a line in northern BC (a job that Japanese Canadians would be assigned to do as ‘forced labour’ during the internment years). More than 8000 Japanese immigrants arrived in Vancouver in the first 10 months of 1907. In July, 1,100 Japanese men arrived on the S.S. Kumeric. They were contracted to work for the Canadian Pacific Railway. Racial tensions were running high.

* * * * *

Having personally taken the 360 Riot Walk in 2019, I recall that the experience was a little surreal, overlaying images on the iPad and the sounds imposed on the real-time images was jarring at times and certainly challenged my perceptions of the past. Tsang manages to create a time machine of sorts that bridges time periods and layers of cultural change and perception.

Before taking the 360 Riot Walk, I did a little research which made the experience extra meaningful. The tour took me past businesses that were formerly owned by the descendants of friends (e.g., Maikawa, Kay Mende) and, most poignantly, 247 Hastings Street, where my grandfather had settled for a time, now part of the Shiloh Place home.

I am reminded too that it was a young William Lyon MacKenzie King (1874-1950), who was sent by Ottawa as labour minister to conduct a Royal Commission to assess the damages after the 1907 riot. He submitted his PhD thesis, “Report of the Royal Commission Appointed to Inquire into the Methods by Which Oriental Labourers Have Been Induced to Come to Canada” to Harvard (1909). The Chinese Canadian community was recompensed with $26,000 and the Japanese Canadian community, $9000. It was the same Mackenzie King who, in 1942, as prime minister, ordered that 21,000 Japanese Canadians be put into prison camps (1942-1945).

Subsequent to Vancouver’s Anti-Asian riot, in Seattle on September 13, 1907 there were attacks on 32 Punjabis who had fled the Bellingham mob, boarding a ship heading to Alaska looking for work. White passengers protesting to the captain had them removed. There were riots in Danville, WA (October 3, 1907); Everett, WA (November 2, 1907) under the banner of “The Hindu Must Go;” and in Live Oak, CA (January 1908) when 78 Punjabi railroad workers were driven out by racists in that community. Two were arrested. The case was dismissed.

Rethinking the 1907 Riot: Six Essays

By recontextualizing 1907 through a 2024 Asian Canadian lens, these insightful essays shed new light on this Canadian race riot that few still know about. More importantly, these essays help readers understand where the Chinese and Japanese communities that were affected by the riot stand today: “Uprooting the Racism in Our Ranks: Reflections from a Labour Perspective,” “Why We Say Powell Street and Not ‘Japantown’,” “The Bellingham Riot,” “A Changing Chinatown: On Gentrification and Resilience,” “Census Making and City Building: Data Perspectives on the 1907 Anti-Asian Riots and the Development of Vancouver,” and “An Urban Rights Praxis of Remaining in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.”

As Patricia E. Roy, professor emerita of history at the University of Victoria and authority on anti-Asian policies in BC writes in the introduction, “Let’s hope that this virtual tour, by introducing people to the area, its history, and its residents, will contribute to the demise of that evil.”

WHITE RIOT: THE 1907 ANTI-ASIAN RIOTS IN VANCOUVER

By Henry Tsang

(Arsenal Pulp Press, 2023, 192 pages, $32.95 Canada/$26.95 USA paperback)

@ 2024 Norm Masaji Ibuki