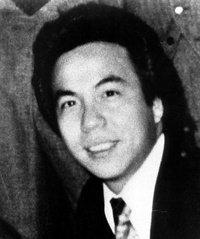

1982 Vincent Chin Murder in Detroit

We both remember the murder of the Chinese American, Vincent Chin. Until then I didn’t realize how visceral Anti-Asian hate, specifically against Japanese, was in America. What effect did Chin’s murder have on you?

JT: My short stay in Nagoya had compelled me to toy with the idea of applying to a university in Japan, and I learned that only two universities would accept kikokushijo (returnees). Sophia (上智大学) offered a humanities program that required me to start from Year 1. International Christian University (ICU) was liberal arts, with a limited offering of Sciences, but they would accept transfer students.

I wasn’t the least bit serious about actually applying, because the majors they offered were lame, but if I were to transfer to a Japanese university, ICU was the program that best fit me. ICU gave the impression of being a religious institution that would indoctrinate me into a Jesus freak. Regardless, I did complete my application with no real intent to attend even if admitted.

Vincent Jen Chin was a Chinese American man who was murdered in Highland Park, Michigan, United States, in 1982

Vincent Jen Chin was a Chinese American man who was murdered in Highland Park, Michigan, United States, in 1982Then the Vincent Chin incident happened. I was in Windsor, right across from Detroit.

As you know, Vincent was mistakenly killed for a Japanese by some agitated auto workers who were laid off thanks to Japan unfairly dumping its well-made Civics and Corollas onto the North American market. Interestingly, they were cheaper in America than in Japan. In effect, the Japanese automakers were giving away samples of their products at a loss, to get Americans hooked on their products, so that they would buy Accords and Preludes at a much larger profit.

Sounds familiar eh, like a drug dealer? I did not approve of the trade practices of my motherland, but I surely did not appreciate the reactions of the UAW destroying Japanese cars with their sledge hammers, and the media taking on a perspective with an anti-Japanese sentiment.

Vincent was not Japanese, but I was.

I felt like it was supposed to be me, and that this poor guy lost his life on my account. Surprisingly, I did not feel spite towards the perps, but more toward the sly Japanese businesses that were plotting to take over America. Apparently, I too was a victim of biased media agenda setting against the Japanese for the sake of protecting American pride.

My Japanese identity had been accentuated by the Vincent Chin incident. It was a wake up call. I was no longer safe for being what I was. Those who know me would fully recognize me as a Canadian, but strangers could not see beyond my Asian face, and their anti-Japanese sentiment could be easily felt.

I was torn between pursuing my goal as a geologist in Canada, or starting anew at an artsy-fartsy Christian mission school in Japan. If it wasn’t for Vincent’s killing, it would have been a no-brainer to remain in Windsor, but his incident prompted me to make the last minute decision to return to Japan.

So, it was off to Japan for your next phase of education?

JT: Having been raised a country hick in Northern Ontario, Nagoya was a better place for me than Tokyo, despite it being as big as Toronto at the time. It had this small town inaka atmosphere to it. I wanted to go to Nagoya University, but unfortunately, they had no programs for expat kikokushijo.

After graduating from ICU, I could have easily attained a job at a major corporation as did my fellow kikokushijo classmates, given that Japan was in the peak of its overseas expansion. Rather, I decided to follow my dad’s footsteps into the world of scholars, to obtain a PhD and become a professor. Nagoya University’s graduate admissions test was super challenging, and my Japanese ability was not quite yet ready to allow me to gain admissions, but their PhD exam was much less intensive, so I opted to attend a Masters program in Sociology at Saitama University first.

I was able to brush up on my Japanese at this big national university north of Tokyo. After finishing my Masters, I was ready to take on the admissions exam for Nagoya. They liked the idea that I was kikokushijo, and I got accepted, turning down an admissions offer from U of Minnesota, which was my back-up plan. Yes, Minnesota, back to the frozen wastelands, eh? But it was close to home in the Soo, and my parents.

The reason I thought about studying in the USA was that Japanese universities would not give you a PhD degree in the humanities and social sciences at that time, because the professors did not have PhDs, and you did not need one to become a professor. My dad was known as Dr. Takai, and I yearned for that title too (other than “Chink”). However, I chose to remain in Japan, and pursue a career in academia.

But why the USA and not Ontario? Ontario universities did not offer programs in Communication at that time. If they did, I sure would have opted for a school in Ontario over Minnesota.

Two years into my program at Nagoya, a lot of things happened. My parents got divorced, my dad remarried a woman from Kochi, Japan, and he was diagnosed with terminal cancer. Dad chose to return to Japan since they could not treat his illness in the Soo. Hence in 1989, our whole family was back in Japan, although at different places.

I got a job offer from Hiroshima University, a leading research university, and while I was still not finished [with] my PhD program, I thought of how much dad was proud of me when I announced that I wanted to become a professor, and now that he was terminally ill, I decided to withdraw from the program without the ABD (all but dissertation) qualification.

I was appointed Assistant Professor, my first position as a professor, and Hiroshima was relatively close to Kochi, where my dad was undergoing treatment. My dad passed away soon after, and losing him made me worry about my mom. I suddenly got the urge to go back to Nagoya to take care of her.

There was an opening at Nagoya City University, so I applied only three months into my term at Hiroshima, and they gave me an offer. I spent just one year there before moving back to Nagoya to be with my mom and brother. Not that I was a mama’s boy mind you. Our family had always been tight, having spent so much time in a place where we were the only Japanese.

Nagoya City University promoted me to Associate Professor not long after transferring, and because I would play a central part in their future plan for an international oriented department, they gave me a sabbatical leave to attain a PhD in Communication, allowing me to spend two years at University of California, Santa Barbara (UCSB). I finished my coursework, and took the necessary exams to become ABD (All-but-dissertation), and returned to my job at Nagoya City University to concurrently work on my dissertation, which I eventually finished to obtain my degree.

1992 Rodney King Riots

I was living on an island off the coast of BC in 1992. I remember watching the LA riots on TV after the police assault on Rodney King occurred; this added another layer of complexity to my sense of being Japanese Canadian. I remember seeing Korean-owned businesses being looted, destroyed and burned. My idea of self was evolving into a more pan-Asian sense of being…

JT: In 1992, during the LA riots, I was in Nagoya. I went to California in 1994, so by that time, things had settled down, but the relations between Af-Am and As-Am were still sour, and I would get a huge load of dissing just for walking by. I was astonished at first, like, ‘Jesus, what’s eating that dude? What did I do to piss him off so much?’ I got used to it. A Nikkei friend who came from Gardena (which borders on the infamous City of Compton) taught me a lot about the street history between our two groups.

I fully stand with my Asian-American brothers and sisters on this issue. White cops beating up a black guy, but why did the Asian community have to get into the mix? It’s that grocery store thing, where a Korean store owner opened fire on a black girl who was leaving the store without paying for her stuff. Immigrants seeking a new life in America have little choice on where to set up their businesses, so they can only afford to have a store in the rough areas.

You can imagine they would be victimized by theft and robbery on a daily basis. The people of the community should be appreciative of their courage and perseverance to open a store to serve the people in their neighbourhood, yet when the riots happened, they were the ones to be attacked. Maybe the patrons perceived themselves hounded by the store clerks whenever they entered their stores, getting ripped off on higher prices (to recover losses from theft). Without them, though, they would not have any store in their vicinity, and they would need to drive miles away to shop.

The Aftermath of the Rodney King Riots (Photo by Mick Taylor from Wikipedia)

The Aftermath of the Rodney King Riots (Photo by Mick Taylor from Wikipedia)Of course, I am not saying that shooting an unarmed teen is condonable, regardless of the circumstances, but why is it all about the teenager, and not the Asian proprietor, and the troubles she had to bear leading to it? We don’t hear about her side of the story. BLM, of course, but how about a bit of ALM too?

© 2023 Norm Ibuki