Nobuko Miyamoto, a third-generation Japanese-American, has had what is commonly called a "life full of ups and downs." However, if "life full of ups and downs" means being buffeted by the turbulence of the times and encountering unexpected situations, then in Miyamoto's case, in addition to that, her life is full of ups and downs, as she has moved forward while creating ups and downs based on her own beliefs.

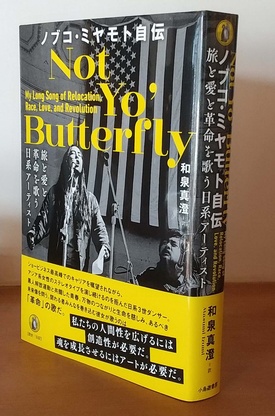

"Nobuko Miyamoto's Autobiography: A Japanese Artist Singing of Travel, Love, and Revolution" (translated by Masumi Izumi, Takanashi Shobo), published last November, is packed with her dense life of about 80 years since her birth in 1939. However, it is not suffocating to read.

As an artist who expresses himself through song and performance, and as a social activist, he faces one wall after another, never compromising his beliefs and always finding a way forward in the face of adversity, which is sometimes sad but also exhilarating.

No one can choose where they are born or the circumstances they are in. To a greater or lesser extent, everyone carries the fate of their birth with them. However, how they change it, or whether they just go with the flow, varies from person to person. In the case of Nobuko Miyamoto, she is strongly restricted by her Japanese origins, but as an extension of her intense awareness of this, she continues to live her life changing what needs to be changed.

This autobiography is a reflection of his life in his later years, summarizing the facts of his past. In other words, it is a summary of his way of life.

The turbulent times begin at her birth. Her autobiography begins thus:

——I was born somewhere I didn't belong. By the age of two, I was an enemy, a spy, a threat to America's internal security. Soon, along with 120,000 other people who looked like me, I was taken to what the adults called "camp" back then. But it wasn't summer camp. ——

Nobuko's mother's father was from Fukuoka Prefecture and came to California in 1905 to pursue his dream of rice farming. He married a Japanese woman who came from Japan as a "picture bride," and Nobuko's mother was born. Meanwhile, Nobuko's father's father was from Kumamoto Prefecture, traveled to America to work as a railroad worker, and eventually married a white woman, and Nobuko's father was born. Nobuko was a third-generation Japanese American, born to a second-generation Japanese mother with Japanese ancestry and a second-generation Japanese father who was half Japanese and half white.

Two years after she was born in Los Angeles, war broke out between the United States and Japan, and Nobuko's family, like other Japanese Americans, were interned, but her father volunteered to work harvesting sugar beets in Montana, and the family was sent to a farm in Montana. After that, those who had sponsors inland were released from internment, and they moved to Idaho, where her paternal grandfather owned land.

When the war ended, the family returned to Los Angeles and tentatively began a new life, but Nobuko became aware of her position as a Japanese minority in America, and at the same time, she became sensitive to what it meant to be a minority and to the discrimination and prejudice that come with racial differences.

Her home was in an area where blacks, Japanese, and other people of color lived, but her mother warned her, "Don't play with Kuro-chan's kids!" Meanwhile, a white boy yelled abuse at Nobuko as he passed by, calling her a "filthy Jap!" Furthermore, a Japanese girl told her, "We don't want to play with people like you!" This is because Nobuko has white blood in her.

Nobuko started to learn dance as soon as she went to school and devoted herself to practice. As a minority of Japanese descent, she was told that she had to be twice as skilled as the average person to be accepted in the dance world, so she worked hard. Perhaps it was because of this that she soon became a professional dancer. She also appeared in the films "The King and I" and "West Side Story," and performed on major stages.

But she realized that she was expected to play characters of Japanese, Asian or colored origin, roles expected of her by white people. She studied to become an actor, but found it hard to accept the types of roles she was expected to play: a geisha traveling the West in the TV series "Laramie," a maid on "The Doris Day Show," and a Japanese spy in Bill Cosby's first series, "I Spy."

Moving away from the model minority

"I was part of a confused generation that thought they were American even though they looked Asian," she says, but she gradually emerged from that confusion and became aware of and established her identity as a third-generation Japanese American. She was quiet, obedient, and patient. She "escaped from her model minority status" and aimed to build solidarity not only with Japanese Americans but with Asian Americans as well.

In the 1970s, he went to New York and worked for Asian Americans and was involved in the black movement. He searched for what his songs were and what culture and art should be. He thought of art for the people, not the elitist art of Western culture.

Around this time, in her private life, she gave birth to a boy with her black boyfriend, who had connections to the black liberation movement leader Malcolm X. At a time when single Japanese mothers were rare, she was troubled and thought, "I have committed a terrible sin against my Japanese family that I will never be able to undo." However, with the support of the head priest of a Buddhist temple in California, she gave birth to the baby and her mother eventually accepted it.

In 1978, he and his friends founded the nonprofit arts organization Great Leap and began grassroots multiculturalism initiatives, including Fantango Obon, a combination of the traditional Mexican gathering of music and dance, and the Japanese summer festival of Obon.

The attempt to combine efforts to spread Fandango among Mexican and Latino communities across the United States with a traditional Japanese event is the culmination of previous efforts to connect people of different cultural backgrounds.

Nobuko had been searching for horizontal connections that transcend race and culture in America, but it wasn't until the 21st century that she got in touch with her roots in Japan. On her first visit to Japan, she was filled with anxiety about whether her relatives would accept her. However, it turned out to be an unfounded fear, and she was welcomed with warmth and understanding, which made her realize something for the first time.

"Our relatives in Japan remembered us, missed us, and suffered for us, yet we barely knew them. We were all just trying to survive and trying desperately to become Americans."

Starting from his roots as a Japanese American, he seeks solidarity with other minorities and people, and eventually finds a connection with his roots. His autobiography is also a record of that long journey.

© 2024 Ryusuke Kawai