A month ago, I visited the Crocker Art Gallery in Sacramento during a weekend trip to the city. In California, the Crocker houses some of the most impressive collections in the state. Many of the collections in the museum focus on the history of “Old California,” in the period between the Spanish Colonial Period through Mexican Independence and into California’s early decades in the Union.

As I wandered through the hallways of the Early California exhibit, I was surprised to find a case of decorative ceramic ware that included several plates and cups with Japanese illustrations of people and creatures. All of them bore the distinct style of their creator, Toshio Aoki. Since the labels on the cabinet said little about Aoki’s life, beyond his residency in California at the turn of the 20th century and his death in 1912, I decided to do my own research into Aoki’s artistic career.

To be sure, Aoki’s name is not unknown to art historians. Aoki is featured in the Stanford University Press’s 2008 volume Asian American Art, A History, 1850–1970, and was described by coeditor Gordon Chang as “the most important Japanese painter in California” during the early 20th century. Japanese art historian Chelsea Foxwell has documented the influence of Aoki’s artwork upon the Japonisme movement in the United States during the early 20th century for the journal Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide.

Both rightfully argue that Aoki built up a significant cachet among artists in the U.S. for popularizing the Nihonga style, and helped foster interest in Japanese aesthetics among elite Americans. Yet less has been said about Aoki’s early travels across the United States, or about his connections to the Japanese American press. This article uncovers the story of Aoki’s early life in the United States, and provides a view into the bustling artistic scene among the Issei in the United States.

Little is known about Toshio Hyōsai Aoki’s early life. According to US Census records, he was born in 1854 in Japan. One newspaper account states that Aoki was from Aizu, and served as a soldier on the side of the Shogunate during the Boshin War of 1868-1869. When Aizu surrendered to the Emperor’s armies after months of brutal fighting, Aoki was taken prisoner by the Emperor’s army and abused in captivity.

After the war, Aoki moved to Yokohama to restart his life, and began studying ceramics. According to Chelsea Foxwell, Aoki joined the Deakins Brothers and Company, a Yokohama-based exporter of Japanese goods to the United States that employed artisans.

In 1874, Aoki migrated to the United States and settled in San Francisco with the intent of furthering his artistic career. In 1885, Aoki joined the San Francisco-based Japanese Village Company. Originally incorporated in Sacramento, the Japanese Village Company put together a travelling crafts exhibition featuring the work of Japanese artisans that toured the United States in 1886.

Within a short time after Aoki joining the company, his beautiful artwork and his gregarious personality began garnering the attention of reporters. One of the earliest mentions of Aoki in a U.S. newspaper was in the Philadelphia Times in March 30, 1886. Titled “A Wonderful Artist,” the article described the work of a new sketch artist, Toshio Aoki, at the Japanese village in the Horticultural Hall.

Providing one of the few existing accounts in English of Aoki’s early life, the article described Aoki’s long journey to the United States:

“He is only 34 years of age. In the revolution of 1865 he was in the army opposed to the Mikado, which was defeated. He was taken prisoner and treated inhumanely. Some years later he decided to become a painter. He had never been taught the art, but selling everything he had in the world he went to Yokohama and sat down on a mat in the street to paint. Settling in Yokohama he turned his attention to portrait painting and achieved great success at it, making the wonderful wages of one cent per day.”

The author declared that, among the ateliers at the Japanese Village, “there is always a large crowd around the workshop of Toshio Aoki.”

In September 1886, Aoki travelled with the Japanese Village Company to present its exhibit in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. On September 14, 1886, Toshio Aoki married Eva La France before a justice of the peace in Milwaukee. Several newspapers in the U.S. declared that it was the first time that “a Japanese has legally espoused an American lady in Wisconsin.” Interestingly, the justice listed Aoki’s race as “mulatto” on the wedding certificate, instead of the more expected term “oriental”.

Following the end of the Japanese Village Company’s tours in 1887, Aoki and La France moved to San Francisco, California. Although it is uncertain what happened to Eva La France – some sources claim she died, while others state the couple divorced – they ceased living together by 1900. During these years, Aoki began to build up his career as an illustrator and producer of ceramic ware.

In 1888, Aoki listed himself as an employee of George T. Marsh’s import business designing curios and plates. Aoki worked with Victor Marsh, the head of the import firm G.F. Marsh and Company, to arrange exhibits of Japanese arts and craft. Some of the crafts they displayed included Aoki’s signature ceramic ware, which bore his illustration style and signature. Among these were caricatures of food personified as Japanese deities. Several examples of Aoki’s “Japanware” reside in collections such as the Crocker Art Museum – which houses his plates showing anthropomorphic food deities - as well as the Cantor Collection at Stanford University.

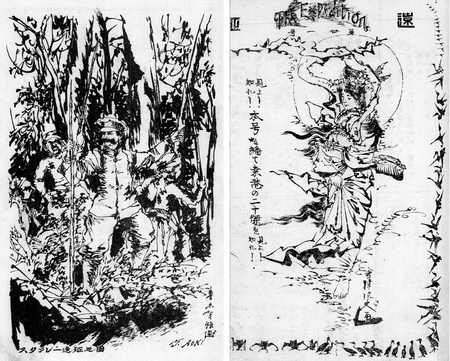

It is during these early years that Aoki began producing art for the Japanese American press. In 1891, Aoki began work as an illustrator for the new San Francisco-based Issei magazine Ensei, or “Expedition.” Described as a “pioneer paper” by scholars of early Japanese America, the magazine targeted readers in Japan and the US and offered adventure stories of expeditions outside of Japan.

One of Aoki’s illustration for Ensei from August 15, 1891, depicts Welsh-American explorer Henry Morton Stanley during one of his expeditions into Africa. Others, like his depiction of a man wandering an island, served as a cover image for an adventure story in the style of Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe. The dazzling imagery of Aoki’s illustrations well complemented the adventure themes of the stories.

Several of Ensei’s covers also showcased Aoki’s dazzling sketchwork. In one cover from August 1893, Aoki drew a profile of a geisha floating among the clouds – similar in style to his ceramic illustrations of Japanese deities. Others depicted children, swordsmen, and samurai in ornate fashion. Aoki continued to provide the cover art for Ensei until the magazine’s last issue in December 1893.

In later years, Aoki continued to illustrate for Japanese American newspapers in Los Angeles. For example, several illustrations in the short-lived Los Angeles Japanese Advertiser, or Rafu Maru Maru Chinbun, from April 1907 include illustrations in Aoki’s style.

Aoki engaged in freelance work for several publishers presenting Japanese stories. In 1892, Aoki provided illustrations for Flora Best Harris’s translation of Tsuruyuki’s classical story Log of a Japanese Journey from the Province of Josa to the Capital. Aoki received praise for his ingenious art style in several reviews, such as the New York-based literary review The Critic. In all, Aoki emerged as one the most distinguished and prolific graphic artists among the Issei in North America.

At the the close of the 19th century, Aoki came to Pasadena, California, in the company of Victor Marsh to open an exhibit of Aoki’s caricatures. He fell in love with Pasadena, and decided to permanently settle there. Once in Pasadena, Aoki opened the city’s first Japanese bookstore. It was during this time that Aoki received additional work as an illustrator for several newspapers throughout California.

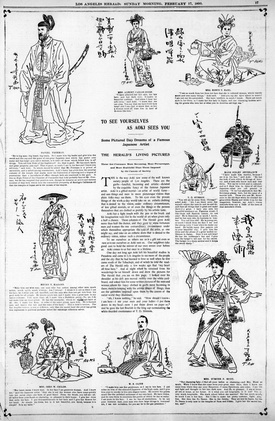

Between 1895 and 1900, Aoki’s art appeared in the Los Angeles Herald, the Los Angeles Examiner, and The San Francisco Call. Like his designs for Ensei, Aoki’s illustrations for The Call included whimsical portrayals of folklore and adventure.

Although Aoki made his mark on the art world by reproducing Japanese art for Western audiences, he had an eclectic style that drew on various techniques. For example, one of Aoki’s oil paintings in the Canter Collection at Stanford depicts persimmons in an Indian basket. Other examples from his newspaper collection depicted European characters, such as his drawing of Robinson Crusoe for an issue of Ensei.

In an interview with the Los Angeles Herald, Aoki described himself as a friend of the famous Scottish American artist William Keith, who made California landscapes famous through his oil paintings, but told readers that he actually preferred Russian art. Unfortunately, his art also reflected racist views of the period. In one of his illustrations for the Los Angeles Herald, he depicted himself next to a table of severed heads of Chinese men. He later stated in an interview that he despised the Chinese and thought poorly of them.

From his studio in Pasadena, Aoki travelled frequently to San Francisco and Los Angeles for business meetings and social gatherings. His work attracted the attention of several elite Californians fascinated by Japanese culture, and they began inviting Aoki to join their Japanese-themed parties. For example, at an 1895 fundraiser for the San Francisco Pioneer Kindergarten Society, Aoki “dashed off artistic Japanese sketches in watercolor for the benefit of the society. He painted birds, storks, figures, bits of landscape and humorous subjects, every one of which was highly praised.”

In a special piece for the Los Angeles Herald, Aoki produced caricatures of Los Angeles’s elites as Japanese lords and geishas, including lumber baron Thomas Douglas Stimson, Mary Hunt, the wife of famed architect Sumner Hunt, and land developer Daniel Freeman. At a cherry blossom-themed dinner held at Toshio’s studio in Pasadena in March 1903, guests included the likes of John D. Rockefeller, James Pierpont Morgan, and Madame George Pullman. For his obituary, journalists claimed that Aoki was bestowed with a gold medal by Queen Victoria for his artistic feats.

Although Toshio Aoki frequented social events, he lived a solitary life. Newspaper accounts and Census records list Toshio as a bachelor after 1900. Over the years, Toshio’s health declined. Nonetheless, he became a family man. During a trip to San Francisco in 1898, Aoki adopted a seven-year-old girl, Tsuru. The niece of the famed geisha Sadayakko, Tsuru was brought to San Francisco by her aunt and by her uncle Kawakami Otojiro, who booked a tour of the United States. According to Chelsea Foxwell, they sought out Aoki, with whom they were previously acquainted, to design a set for their tour. In the end, the couple decided to entrust Tsuru in Toshio’s care.

As a father, Toshio provided Tsuru with opportunities to foster her artistic creativity. In 1903, when Broadway producer David Belasco hired Aoki to design the sets of his Japanese-themed melodrama The Darling of the Gods, Toshio took Tsuru with him to New York City and enrolled her in ballet classes. Ultimately, Toshio decided to enroll Tsuru in a boarding school in Colorado Springs and visit her during his trips across the country.

In later years, Toshio Aoki struggled with health problems. He lived in the Hotel Green for several years, and eventually left Pasadena and moved to San Diego. He died in San Diego on June 26, 1912. After Toshio’s death, Tsuru was entrusted to the care of an anonymous woman reporter working for the Los Angeles Examiner. The woman, likely an acquaintance of Toshio, enrolled Tsuru in drama classes. From there, Tsuru became famous in her own right as one of the first Japanese American women to appear on the silver screen. Aoki regularly appeared in silent films alongside her future husband, the famed star Sessue Hayakawa, as well as directing and producing. As an homage to Toshio’s impact on Tsuru’s life, Hayakawa and Aoki included one of Toshio’s paintings in the 1919 film The Dragon Painter.

Toshio Aoki’s career in the United States offers a rare glimpse into the world of the Issei and the early formation of art circles among Japanese Americans, long before the heyday of more famous artists like Chiura Obata. His work also captured the “pioneer spirit” that was embraced by the Issei, which sadly included anti-Chinese sentiment.

More broadly, Aoki also captured the spirit of Japonisme that was popular throughout the United States in the late 19th century. For the rich of California society, Aoki provided exoticized views of Japan and portraits of Japanese. Ironically, it was at this time that the anti-Japanese movement began to gain momentum in California, and within a decade Japanophilia gave way to bitter anti-Japanese racism. Today, his artwork should be remembered as relics of a bygone era in California history, one that prominently features the early immigration of Japanese to California. Although his artwork remains as a tangible legacy of Aoki’s influence, perhaps his most noteworthy accomplishment was as the adopted father of Tsuru Aoki – one of the first major Asian American actors in Hollywood, and a true pioneer performer.

© 2023 Jonathan van Harmelen