David Mura is an Asian American poet, novelist, playwright, critic and performance artist whose writings explore the themes of race, identity and history.

In 2018, Mura published a book on creative writing, A Stranger’s Journey: Race, Identity & Narrative Craft in Writing, in which he argues for a more inclusive and expansive definition of craft. Mura has published two memoirs, Turning Japanese: Memoirs of a Sansei, which won the Josephine Miles Book Award from the Oakland PEN and was listed in the New York Times Notable Books of the Year, and Where the Body Meets Memory: An Odyssey of Race, Sexuality and Identity (1995).

His most recent book of poetry is The Last Incantation (2014); his other poetry books include After We Lost Our Way, which won the National Poetry Contest, The Colors of Desire (winner of the Carl Sandburg Literary Award), and Angels for the Burning. His novel is Famous Suicides of the Japanese Empire.

As a playwright, novelist, and poet, what do you enjoy about each writing process? How do you approach your different projects?

In creative writing, you should be engaged in a process of discovery—of new ideas and analysis, of narrative and character, of perceptions, feelings, memories, of language and new verbal combinations—and this is because you are trying to connect with the unconscious sources of your creativity. In my book A Stranger’s Journey: Race, Identity & Narrative Craft in Writing, I define creative writing as the search for and creation of a language to express what we know unconsciously but don’t yet have a language to express.

So an emphasis on critical judgement or conscious planning can often inhibit rather than aid in the process of writing. I know this because I was drummed out of grad school with seven incompletes and had a severe case of writer’s block. But then I read these essays in Writing the Australian Crawl by the American poet William Stafford where he emphasizes that writing is a process rather than an activity geared toward product, and he completely changed my thinking when he declared, The key to writer’s block is lower your standards.

What he meant was that we can all produce sentences, but then our conscious or critical mind starts to critique those sentences and eventually we clam up—or rather our unconscious stops working and says to the conscious mind, Screw you, we’re not going to work anymore for such a judgmental boss.

The mistake is in thinking the conscious mind is more intelligent and creative than the unconscious mind. This is why I hate the five paragraph essay which so many are taught in school—it emphasis conscious planning and organization rather than discovery and the unexpected.

This is not to say I don’t write a lot of things that don’t work; I do. But as I always tell my students, You can revise something, you can’t revise nothing.

Moreover, writing is a process and if you’re writing regularly, you’re telling your unconscious to stay open, and this occurs not just when you’re writing but in between the writing times. And so again, there’s a process of discovery which, if you enter into it, your conscious mind does not control and perhaps may not understand at first.

My essay books and poetry books often start with a core of essays or poems at the beginning. Gradually a structure, a theme, a way of proceeding arises, and there’s a process of putting things in and taking things out, refining the direction and organization of the manuscript, and a discovery of the true subjects of the book.

I find the process of revision enjoyable. Yes, sometimes it’s frustrating, especially when I’m at the point where it’s hard for me to see what’s working and what isn’t. It’s far easier for me to look at other’s or student writing and to detect where the writing is strongest—where it’s almost always the unconscious is digging up something new, something deeper, and if the writing is really working, something scarier or more threatening or painful or difficult.

But you can’t get to that in an instant or often in the first draft. You have to keep chipping away, to keep digging. Again I often tell my students, You don’t get ten feet deep with the first shovel. But you can’t get to ten feet if you don’t make the first shovel.

With narrative work, there’s often a point where I have to stand back and try to consciously organize or outline the material, and then story board it—look at it for ways of improving or restructuring the narrative. This takes place not at the level of the sentence or paragraph or even the chapter, but more in mapping the overall structure of the narrative. It’s important work, but often writers are not taught the techniques and structures of traditional Western narratives (narratives in African and Asian cultures often use different structures); it’s these Western narrative structures that I examine in the second half of A Stranger’s Journey.

Overall I am amazed at the writer I’ve become, in part since so much of my work deals with my own ethnic and racial identity and the subject of race. Much of my writing has been against the grain of my upbringing. Mostly in reaction to their unjust imprisonment as teenagers during WWII in the Japanese American concentration camps, my parents tended to eschew their ethnic roots and tried to raise me to assimilate into a white middleclass identity.

It was only in my late twenties, after beginning to read Black writers, that I finally realized I was not white, I was never going to be white, and I had to begin trying to discover my own identity–what it means for me to be a third generation Japanese American (Sansei), an Asian American and a person of color; how my life and my family’s history fits into the story of race in America.

In many ways then I wrote my books because when I looked at my book shelves there were few books about anyone remotely resembling my own racial and ethnic identity and so I had to write myself into that identity, into an understanding of my family’s and America’s racial past.

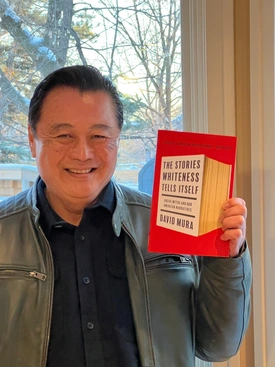

This has culminated in my last book, The Stories Whiteness Tells Itself: Racial Myths and Our American Narratives, which contrasts white and Black historical and fictional narratives and how white narratives tend to follow the rules of Whiteness as an ideology—a set of beliefs, ideas, rules and practices for white identity.

I hope to learn more about the Vancouver literary community and the Asian American community and how they might differ from my own communities in Minneapolis/St. Paul as well as learn about the differences between Canadian and American culture. I’ll be working on a set of essays on Asian American issues and identity during my residency.

*This article was originally published in LiterAsian 2023.

© 2023 Sophie Munk