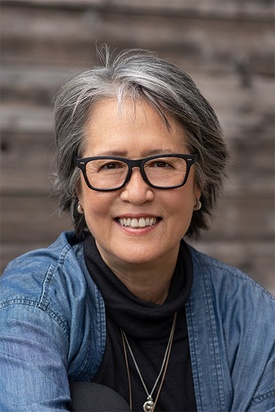

During the book tour for A Tale for the Time Being, author Ruth Ozeki shared how her characters speak to her when she writes. Speaking to a crowd of readers at a library, she explained that she hears the tone, attitude, and inflections of characters’ voices in her head. An audience member asked Ozeki to compare the experience of hearing characters’ voices inside her head to that of his son, who heard voices outside his head and was considered unwell.

For Ozeki, the question sparked questions of her own. Often for authors and creators, hearing voices inside your head and making up stories is celebrated. Meanwhile, the subjective experience of hearing voices outside of your head is pathologized and considered abnormal.

“I was thinking about this relationship we have to voices as a spectrum. When do we call it normal, and when do we call it pathological,” Ozeki tells Nikkei Voice in an interview. “As a creative person, I’m very grateful that we live in a culture where the fictional voices that I hear of characters are considered to be valuable and creative instead of pathological.”

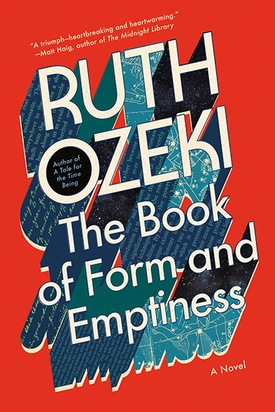

Ozeki explored these questions in her new book, The Book of Form and Emptiness, which hit bookstores on Sept. 21. The 560-page book is an exploration of loss, growing up, and our relationship with things.

Ozeki is an American-Canadian author, filmmaker, and Zen Buddhist priest, who teaches at Smith College. Her books have garnered international acclaim, and her third book, A Tale for the Time Being, won the LA Times Book Prize and was shortlisted for the Man Booker prize. Her novels ask questions about science, religion, environment, and pop culture through interweaving narratives and empathetic characters.

Narrated by the very book in the readers’ hands, the sentient book tells the story of 13-year-old Benny Oh. After his father, Kenji, dies in a traumatic accident, Benny begins to hear voices in the objects around him. A Christmas ornament cries out in pain when stepped on, a windowpane laments the death of a little bird that flew into it, and toys at his therapist’s office empathetically whimper for the pained children who play with them. Once Benny’s mother, Annabelle, begins hoarding clutter in their tiny apartment to deal with her grief, the voices multiply and become unbearable.

By giving voice, feeling, and sentience to all of the inanimate objects in Benny’s life, Ozeki raises questions about our relationship with all of the stuff that occupies our life. Annabelle’s relationship with clutter is sentimental, and she feels a deep connection to everything she collects, they could be used for crafts, connect her to her dead husband, or remind her of a more hopeful version of herself.

As Annabelle tries to get rid of the clutter in her home, she follows the guidance of a Japanese Zen Buddhist priest’s decluttering book. The fictional Zen priest was inspired by the real-life Japanese cleaning guru, Marie Kondo. In Kondo’s decluttering regiment that took the West by storm, Ozeki found the practices felt distinctly Japanese. There are Japanese customs and traditions that foster a sense of gratitude and caring for objects, like there is a spirit or being within them, which Ozeki explores in the book.

“I’ve always been fascinated by our relationship to things. One of the things I noticed about [Marie Kondo] is a lot of the practices that she’s advocating are practices that are simply Japanese. In Japan, historically and culturally, we have a more attuned relationship with our belongings and with our possessions,” says Ozeki.

This belief exists in traditions like the Buddhist and Shinto Festival of Broken Needles, called Hari-Kuyo. Once a year, communities hold a ceremony for all the broken sewing needles at the local shrine. Locals place the long-serving sewing needle in a block of tofu as a way to thank it with a soft eternal resting place, explains Ozeki.

“I think that would help us all if we lived more like that. The way capitalism works, obsolescence is built into objects. It’s a design feature, not a bug. The world is filled with too much broken stuff,” says Ozeki. “I think that we all feel that there’s something wrong with treating objects as if they’re just disposable things, we have an attachment to objects, and I wanted to kind of investigate that.”

Benny, a sensitive and receptive boy, can sense the spirit or being in all objects by hearing their voices. Like Benny, Ozeki also had her own experiences hearing voices outside of her head, a memory sparked by her talk at the library. For a year after her father died, she would hear his voice. Behind her, while doing something ordinary like folding laundry or washing dishes, Ozeki would hear him clear his throat and say her name.

“I would turn around, and then, of course, he wouldn’t be there,” says Ozeki. “It would be very surprising because it felt so real, and then I’d remember, oh no, he’s dead. And those feelings of grief and loss would come back.”

Another voice Ozeki hears—which many may relate to—is the voice of her inner critic, a negative voice in her head that criticizes and questions her work. These voice-hearing experiences are common for many and raised questions for Ozeki about what is considered “normal” which she explores in the book.

“If you really think about it, even for a moment, you realize that “normal” is a cultural construct. What I’m hoping, is that we widen what our definition of normal is. We allow normal to become more inclusive, and widen that spectrum until it includes everybody,” says Ozeki.

To escape the noise of his mother’s clutter, Benny finds refuge at the public library. There, books are on their best behaviour and only talk when pulled from the shelves and opened. At the library, Benny meets a cast of characters like Slavoj, a Slovenian poet, and Alice, also known as The Aleph, a compassionate and creative artist with a pet ferret nestled in her sweater.

Ozeki creates characters often dismissed or ignored in society and portrays them as complex and layered people. When Benny first sees Slavoj on the bus, he looks away. Slavoj is a homeless man with plastic bags stuffed with bottles swinging from the handlebars of his wheelchair and a tattered briefcase on his lap. The Aleph is a teenage runaway struggling with drug addiction.

Yet the two, each in their own way, help Benny find his voice and regain his agency when the voices around him get out of control. Ozeki creates characters that are flawed and complex, their lives and problems are frustrating at times, yet the reader has watched them traverse paths out of their control, understands how they got there, and root for their recovery.

“That’s what fiction does; it exercises our empathetic muscle. It allows us to step into the body and mind of another, and that is an exercise in empathy,” says Ozeki. “That’s what we’re doing when we reading fiction. Just inhabiting another person’s subjectivity—or object’s subjectivity—is a valuable exercise.”

* * * * *

Ruth Ozeki’s new book, The Book of Form and Emptiness is available now across independent and major bookstores. To learn more about Ruth visit, www.ruthozeki.com.

*This article was originally published in the Nikkei Voice on November 16, 2021.

© 2021 Kelly Fleck / Nikkei Voice