Last AAPI Heritage Month in May brought mainstream recognition to my grandfather, Francis Miyosaku Uyematsu, aka F.M. (1881-1978). Fox 11 News aired two separate stories—each the direct result of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Executive Order 9066.

The first story pays tribute to Uyematsu and Fred Yoshimura’s camellias that grace Descanso Gardens today. It is through the excellent research of Wendy Cheng, associate professor and chair of American Studies at Scripps College, Claremont, that we learn more details of F.M.’s camellia sale to E. Manchester Boddy in her article “Landscapes of Beauty and Plunder: Japanese American flower growers and an elite public garden in Los Angeles” (Society and Space, March 2020). Many thanks to Professor Cheng and Fox 11’s Bob DeSantos.

The second story—the forced sale of Uyematsu’s 120-acre estate in Manhattan Beach—can be credited to Chuck Currier, former teacher at Mira Costa High School. He has spent many years on a project to give recognition to F.M. as the former owner of the land that Mira Costa High stands on and teach students about how the Japanese were locked up into concentration camps. Sandra Endo of Fox 11 reported on Mira Costa High’s plans to honor F.M. with a plaque on a cement pedestal located in the center of campus.

Currier’s work prompted videographer Lindsey Fox to create “Manhattan Beach History: The Uyematsu Family and Mira Costa.”

Earlier stories by Lee McCarthy (“Roots that Run Deep,” Los Angeles Times, 2006), and Naomi Hirahara (“Reconsidering the Camellia,” KCET’s Lost L.A.; “A Scent of Flowers: The History of the Southern California Flower Market, 1912-2004”) on Descanso Gardens are foundational to newer research, as well as poetry by my sister, Amy Uyematsu. The following narrative on F.M.’s life is taken from an interview that was published in the 30th-anniversary issue of the North American Branch of the Agricultural Society of Japan’s Bulletin, an interview published by the L.A. Japanese Community Pioneer Center (1975), along with documentation from Cheng’s article.

I have broken up F.M.’s story into two parts in order to share some of the research done on his life’s work. I quote directly from several articles F.M. wrote in Japanese that he had translated into English, so you can see his own thinking.

Part I. Grandpa Cherry Blossom Becomes Camellia King

F.M. Uyematsu came to the U.S. in 1904 at the age of 23. Third son of a privileged family, he had worked as an accountant in his father’s bank in Numazu, Shizuoka Prefecture, and as a bookkeeper of a jewelry store in Osaka. He was of weak physical constitution and was encouraged by his army surgeon uncle to go to America to avoid being sent to the Russo-Japan War front.

After spending some time regaining his health in Salinas, F.M. got his first job as a laborer. He was very impressed by the local Japanese Christian evangelist sermonizing in front of a local Salinas whorehouse, beginning F.M.'s "long faithful religious life." In 1906, he followed the evangelist's successor to Los Angeles, where he engaged in house work for two years while attending English classes every evening.

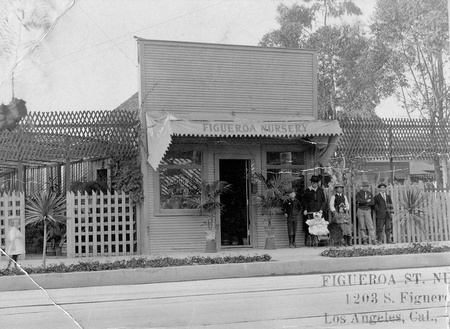

At the invitation of Ichisuke Zaima in 1908, F.M.'s first nursery business was the jointly-owned Figueroa Street Nursery. F.M. recounts: "When he was dealing with living garden trees every day as his business called for, his love for flowers and trees, which had been hidden deep in his mind suddenly was invigorated."

What he recalled was many bedridden days in his parents home in Numazu, with the saving grace of looking out the window and seeing cherry blossoms against the backdrop of Mt. Fuji. It was this memory that inspired him to bring cherry trees and camellias to the U.S. to share the beauty that Japanese enjoy with Americans.

He learned the process of importing from Japan, and bought camellias, cherry trees, and azaleas from Yokohama. In his words: "A novel feature of this enterprise was that I peddled camellias and other plants around the city with a horse and buggy... The camellias costing 12 cents at the time would wholesale for between 50 to 65 cents. I often wondered at this time if it was right to earn money at that rate."

Figueroa Street Nursery did well, enabling F.M. to sell his shares to Zaima so he could develop his own wholesale business. In 1910, F.M.'s wholesale Star Nursery was born with the purchase of five acres in Montebello.

Then came news of the U.S. Quarantine #37 around 1915-16 that would embargo all foreign plants from coming into the U.S. Since Star Nursery depended primarily on importing seedlings from Japan, this embargo would be the kiss of death. Instead, F.M. used the grace period before the quarantine took effect, mustering up all his resources to import top-ranked camellias. He anticipated future shortages and rising costs of camellias, becoming "the top-ranked camellia supplier in the United States of those days," or "Camellia King."

In 1923, he invested $20,000 in a refrigeration system to make plants dormant in order to cultivate in a foreign climate. A Chicago-based horticulture magazine published his experiment, kicking off an active debate. He completed his research in1928; in 1936, a horticulture school in Chiba, Japan established its first freezing system. Saburo Ishihara of San Gabriel Nursery read about his refrigeration project as a horticulture student in Japan. U.S. botanist Dr. Post proudly presented his new thesis on the same topic in 1939. This procedure is now done globally, "indispensable in the matter of garden tree breeding.

F.M.’s mission to adapt Japanese plants to California conditions led him into scientific research. With no more than a middle-school education in Japan, F.M. earned a highly respected reputation as an authority in horticulture.

In 1930, with a special permit from the U.S. Department of Agriculture, F.M. imported 500 top-quality camellias in 113 different varieties, along with 10,000 grains of camellia seeds. He planted these at the 10-acre property he bought in Sierra Madre under his son’s name. With continued success, he purchased 120 acres in Manhattan Beach in 1938.

“Besides camellias, azaleas, and plum trees, about [10,000]* cherry trees of ages 3 to 15 years were planted … 20,000 feet of small and large iron pipes were used in the irrigation system, and … the construction … finished in April of 1941.” F.M. prided himself as “Grandpa Cherry Blossom.” *(From a letter to the superintendent of the National Park Service in Washington, D.C. dated 1961, he says 10,000.)

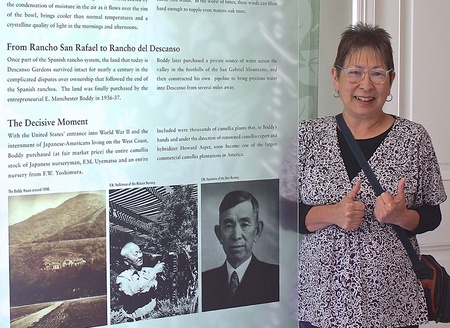

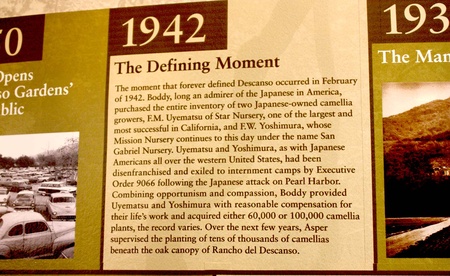

Then, as history happens, Japan bombed Pearl Harbor followed by Roosevelt’s EO 9066 on Feb. 19, 1942. On Feb. 22, 1942, E. Manchester Boddy, publisher of The Los Angeles Daily News and owner of the Rancho del Descanso, approached F.M. on selling his entire camellia inventory for his 169-acre Descanso estate.

Professor Cheng’s article questioned whether Manchester Boddy did in fact pay a “fair price” for 320,000 camellias he bought from Uyematsu, and the 34,200 camellias he bought from Fred Yoshimura of the Mission Nursery in San Gabriel. Boddy only had 300 camellias of his own at the time of purchase. Boddy paid F.M. $50,000 for what he thought was the entire Star Nursery inventory of camellias. However, F.M. planned on continuing his business while incarcerated, and so he still had 20,000 in stock.

Boddy felt cheated since he still had to compete with Star Nursery in the wholesale market, along with feeling that he had paid F.M. a fair price. Considering the times, $50,000 might be seen as “fair” in times of rapacious thievery that all Japanese suffered from their forced removal. F.M. did have the services of the justice-minded lawyer J. Marion Wright, who was the biggest reason why Japanese had any property to come back to after camp. Wright went on to overturn the 1913 Alien Land Law, representing long-time friend and USC classmate Sei Fujii vs. the State of California in 1952.

This “fair price” story was heralded in the Descanso Gardens’ “discovery” of its camellia origins. As former Descanso Executive Director (2005-2016) David R. Brown exclaims:

“This beautiful garden has special significance to me because it is tangible, enduring recognition of the role/contribution of Japanese Americans in the very existence of Descanso. If Mr. Boddy had not purchased those camellias from the Uyematsu and Yoshimura families, there would in all likelihood not be a Descanso Gardens for the public to enjoy today.”

Descanso’s camellia collection is designated by the International Camellia Society as an International Camellia Garden of Excellence.

Under Brown’s administration, the Boddy house was a museum displaying the history of Descanso Gardens, prominently showcasing Uyematsu and Yoshimura along with claims that Boddy paid a “fair price” for camellias that would constitute well over 75 percent of the camellias at Descanso. The Boddy house was repurposed as an event rental space in 2019, and most of the historical panels have been removed.

Manchester Boddy was also a known consultant to FDR’s administration, and before he signed EO 9066, Boddy suggested Owens Valley to be what became Manzanar War Relocation Center. Despite opposition, especially from the L.A. Department of Water and Power, Manzanar was chosen because it had available water to supply a concentration camp of over 10,000 Japanese Americans. As compared to Randolph Hearst, whose newspaper served to stir up anti-Japanese hysteria, Boddy was instrumental in bringing together the initial players who would plan for the evacuation to Manzanar.

Perhaps Boddy is best described by Director Brown:

“In a stroke combining opportunism and compassion, Boddy provided Uyematsu and Yoshimura with reasonable compensation for their life’s work.”

After Professor Cheng published her article in March 2020, she presented her findings to the Board of Directors of Descanso Gardens. As a result, Descanso’s Spring/Summer 2021 Newsletter published “The Camellias of Descanso: The Untold History.” Quoting from this article:

“After Cheng shared her findings, Descanso Gardens pledged to continue learning about its history and begin to tell the true history of the camellias … Along with the question of price, the research also showed that Boddy often took these rare and unique plants and claimed them for himself. While Boddy got the bulk of the named varieties (including dozens of the best varieties obtainable at the time imported from Japan in 1930), there were also a certain number of seedlings as yet unnamed. These can be traced to plants Uyematsu had been cultivating privately. Uyematsu himself had this to say: ‘I was very sad to have to part with my seedlings which I had nursed for over 12 years.’”

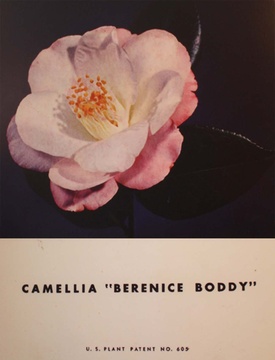

Boddy’s renaming of Uyematsu’s camellia varieties aroused disapproval from the American Camellia Society, which has strict protocol in the naming of camellia varieties. Frank D. Williams and Roy T. Thompson, after one year’s research, credit Uyematsu for 113 camellia varieties that he imported from Japan in 1930. Their findings were published in the “American Camellia Society Yearbook 1950” in an article titled “Star Nursery Camellias.”

One glaring example is a pink variety that F.M. had named “My Darling” for his daughter Marian [Naito] — Boddy renamed it for his wife and it is now commonly known as “Berenice Boddy.”

* This article was originally published in The Rafu Shimpo on June 19, 2021.

© 2021 Mary Uyematsu Kao